The roots of America’s Veterans Day observance can be traced to the 11th hour of the 11th day of the 11th month of 1918, when a cease-fire went into effect, ending hostilities in World War I.

More than 4 million U.S. military personnel took part in “The War to End All Wars.” That number included more than 350,000 Black Americans _ 1,500 from McDowell County, which would become home to the nation’s first and only memorial building honoring Black Americans who served in the war.

Black soldiers and sailors of the World War I era were part of a segregated military and had to fight for respect before they could fight the Germans. African-American units sent to Europe initially were assigned to behind-the-lines support roles, rather than combat. While those jobs were crucial to the war effort, they prevented Black soldiers from proving their mettle under fire. But as casualties increased and pressure from African-American political and civic leaders mounted, two all-Black infantry divisions were created. To lead them, more than 600 Black enlistees were commissioned as officers after completing training at Camp Dodge, Iowa.

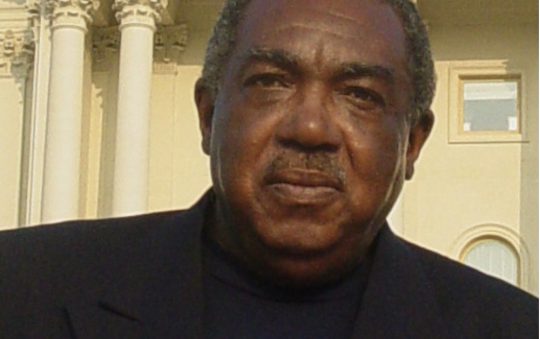

That group included Daniel Ferguson, who grew up in Fayette County, graduated from Charleston’s Garnet High School and attended the West Virginia Collegiate Institute _ West Virginia State University’s forerunner _ before enrolling at Ohio State University. There, he earned bachelor and master’s degrees and set school records as a member of OSU’s track team.

Ferguson took leave from his teaching position at the West Virginia Collegiate Institute to enlist in the U.S. Army as a private in October 1917. After being commissioned as a 2nd lieutenant, he commanded a machine-gun training company through the end of the war, then returned to the faculty at what would become WVSU and taught sociology and economics classes. He later served as dean.

Gen. John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, was opposed to assigning Black infantry units to operate with white troops. To avoid doing so, he assigned the first four Black infantry regiments, to arrive in France in late 1917 and early 1918, to the French army, which had earlier asked for U.S. troops to replace its casualties.

More than 40,000 Black U.S. soldiers were assigned to the French army and were immediately deployed to frontline positions. One such Black regiment spent 191 days at the front _ five days longer than any other American unit _ and its soldiers collected 171 Croix de Guerre medals for bravery. By the time the war ended, Black soldiers fighting with the French had earned more than 500 Croix de Guerre medals.

Black veterans who returned to McDowell County after the war found that the coal boom, which began shortly before their enlistments, had accelerated in their absence, drawing thousands of additional mining families _ many of them Black _ to the state’s southernmost county.

By 1920, 43% of all Black coal miners in the United States were working in West Virginia, most in the southern coalfields. At that time, McDowell had a higher concentration of African American citizens than any other county in Appalachia.

McDowell County’s Black World War I veterans wanted to do their part to bring public recognition to the unheralded but vital role African American military personnel played in World War I. They also wanted a place to meet, conduct veteran outreach activities and socialize, since, because of their race, they were barred from membership in the county’s sole American Legion post.

In the mid-1920s, a group of 16 Black veterans petitioned the McDowell County Commission to build a war memorial building in Kimball to honor African Americans who had toiled, fought and died for their country during World War I.

The commission approved the request, hiring area architect Hassel T. Hicks, himself a veteran of the war, to design the structure, and allocating $25,000 to construct it. Hicks also designed the nation’s first multi-level municipal parking garage in Welch, along with Stevens Clinic Hospital and Williamson’s Coal House Chamber of Commerce Building. He completed the war memorial design in 1927, and the building was finished in 1928.

Among those speaking at its dedication ceremony was G.H. Ferguson, brother of Daniel, who had attained the rank of captain during the war, making him the state’s highest-ranking Black Army officer at the time. He told a large crowd gathered for the event that the war memorial’s four pillars represented the ideals of faith, hope, charity and service.

“The pillar faith represents faith in our country and its institutions,” while the pillar hope “stands for the hope that injustices will cease.” Ferguson said the third pillar represented charity and the fourth stood for service “and should remind everyone of their obligation to community, county, state and nation.”

Ferguson, who commanded a machine-gun training company during the war, returned to Charleston, where he built and operated the 79-room Ferguson Hotel in downtown Charleston.

The Kimball World War Memorial became the home of the Luther Patterson American Legion Post, named in honor of the first Black McDowell County soldier to be killed in the war. It housed an auditorium with seating for 100, meeting rooms, a library, pool tables and a kitchen.

In addition to hosting American Legion meetings and events, the memorial building has been used for reunions, receptions, plays and concerts, including a performance by jazz legend Cab Calloway and His Orchestra.

In the 1970s, as McDowell County’s coal industry and population continued to decline, use of the memorial ebbed and the building began to fall into disrepair. In 1991, the building was gutted by an arson fire, leaving only its exterior shell standing.

Community leaders were determined to restore what remained of the building and incorporate it into a structure resembling its original state.

In 1999, Sen. Robert C. Byrd, D-W.Va., responded to their requests for assistance by pledging to seek appropriations needed to rebuild. Within a few years, $1.2 million was channeled into the restoration effort, which used interior photos of the original structure supplied by the architect’s grandson to guide new construction. The rebuilt war memorial reopened in 2006.

To help mitigate the loss of exhibits and archival materials destroyed in the fire, West Virginia University journalism students, led by professor Joel Beeson, developed an interactive exhibit completed in 2011 for permanent display at the memorial.

“Forgotten Legacy: Soldiers of the Coalfields” involved four years of work by WVU students and faculty who recorded oral histories of McDowell County’s surviving Black World War I vets, conducted research and collected photos, artifacts and memorabilia. The exhibit may be viewed online at www.forgottenlegacywwi.org.

The two-story war memorial is perched on a hillside overlooking U.S. 52 in downtown Kimball. What is now observed as Veterans Day in the United States was initially known as Armistice Day, to commemorate the Nov. 11, 1918, cease-fire that marked the end of fighting in World War I. Armistice Day was celebrated informally until 1938, when Congress made it a legal national holiday.

In 1954, President Dwight Eisenhower issued a proclamation changing the holiday’s name to Veterans Day, to honor veterans of all wars, as well as peacetime service, living or dead.