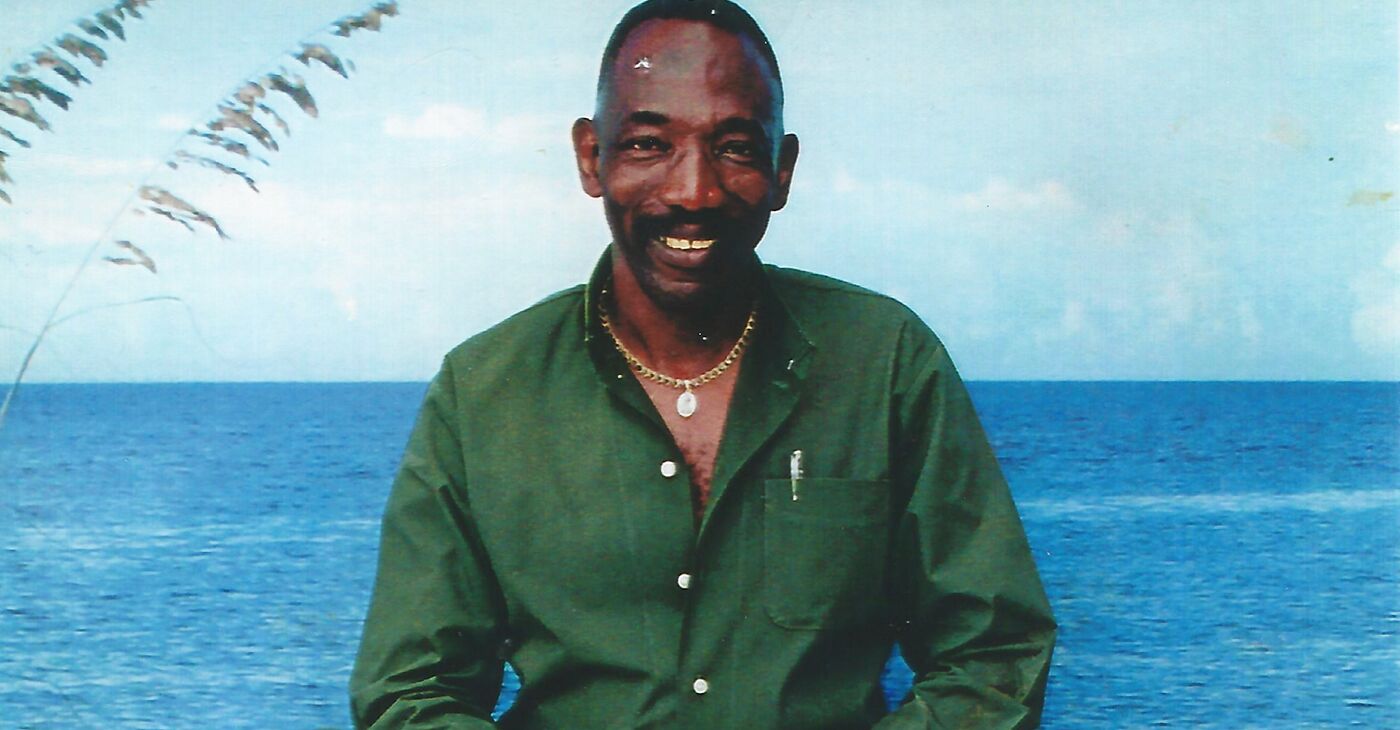

Convicted in 1988 of Nonviolent Drug Offense, Inmate Seeks Redemption and Clemency

To paraphrase the theme song from the “Fresh Prince of Bel-Air,” this is the story of how Rufus Rochell’s life was turned upside down.

It’s not a rags-to-riches Philadelphia-to-California story, like that of Will Smith’s fictional television character. Rochell’s story is the real-life account of how the crack epidemic of the 1980s is inextricably linked to today’s cry for criminal justice reform.

It’s also the story of how the rich and powerful receive special privileges, while the poor and powerless can only dare to dream.

Nearly 20 years into Rochell’s 40-year prison sentence for conspiracy to distribute crack cocaine at a federal prison facility in Coleman, Florida, Conrad Black, a famous billionaire and friend of Donald Trump, was sentenced to the same penitentiary.

Rochell arrived at the prison in 1988 in handcuffs.

Black, an ex-member of the House of Lords who ran a media empire, arrived in March 2008, escorted to the prison in a black SUV with tinted windows.

By prison standards, Rochell and Black made for odd cellmates, but an unlikely bond was established between the two men and they eventually became close friends.

As a new inmate, Rochell was forced to ‘walk the gauntlet,” traversing through a line-up of his fellow prisoners. However, when welcoming Black, who’d been convicted of fraud and embezzlement, prison staff closed access to an entire floor.

Rochell spent much of his time in the prison’s law library, while Black tutored inmates to help them achieve a high school diploma.

Two years after his arrival, Black’s attorneys successfully argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, which ordered the lower court to review its decision in Black’s case. Bail was granted, and Black went back to the high life.

“He deserved it,” Rochell told NNPA Newswire in a telephone call on Monday, February 10, from the federal prison at Coleman. “Conrad Black is a good man, and I don’t have any resentment,” said Rochell.

The letter that Rochell wrote on behalf of Black helped convince a judge to release him. Black eventually received a pardon from an old friend: America’s 45th president, Donald J. Trump.

“I do feel forgotten. I’m probably one of the oldest crack cocaine cases in America in which a person is still incarcerated,” Rochell said during the telephone interview. “But I’m very optimistic. I saw what Kim Kardashian did for Alice Johnson, and I’ve seen people talk about me.”

Amy Povah, president of the CAN-DO Foundation, which advocates for shorter sentences for non-violent drug offenders, put Johnson at the top of its list of federal prisoners who deserve a commutation or pardon from the president. “It’s time for Rochell’s release,” said Povah, who has put together a clemency petition on Rochell’s behalf.

“He should have been home under the First Step Act,” Povah stated. “The First Step Act passed into law over a year ago. It reduced sentences for people like Rufus who are still part of the “100-to-1”: A harsh crack cocaine sentencing disparity that punished primarily African Americans “100 times harsher than [the sentencing for the] powdered cocaine used primarily by white people,” Povah stated.

Due to a backlog in cases, the public defender representing Rochell has yet to file a motion on his behalf, Povah added. “They have said he’s on the list, but we were first to contact the public defender’s office immediately after the bill passed,” she stated.

When approached for comment, a representative at the federal public defender’s office said they weren’t at liberty to comment on cases.

Meanwhile, Rochell still languishes in prison after 32 years. Both of his parents have died. He also lost a niece, and his only child was born shortly after his incarceration. He’s never spent time with his daughter outside of prison walls.

“I’ll be 69-years-old this year and freedom would certainly be nice,” Rochell stated.

Rochell maintains his status as a model prisoner. He has remained actively involved in a prison ministry; has led programs like Fathers Behind Bars; My Brothers 2 Keep Ministry, and Stopping Family Violence.

Rochell has received numerous commendations and is the recipient of four NAACP Humanitarian Awards.

After Hurricane Katrina, Rochell started a campaign that raised money for victims of that horrific storm. He also led a fundraising effort that netted $3,700 for a young boy’s prosthetic eye. Because his mother had no health insurance, the young boy wore an eye patch over his eye at school and endured tremendous bullying, which moved Rochell to action.

“Rufus has watched men walk out of Coleman, who served far less time, while he waits his turn. We submitted his paperwork as a clemency candidate and hope this will bring him home,” Povah stated. “We have helped him every step of the way, with submitted letters on his behalf. The Warden wrote a letter to his Judge, we have written and coordinated with his unit team that is supportive, among other things,” she said.

Rochell also has a standing job offer when he’s released.

“I have a job offer at the museum in Plant City as a curator of artifacts and unique art pieces,” Rochelle stated. “I just need people to remember me. I want to make a big difference in my community. I need that second chance. I have a daughter, two grandchildren, and I’ve got relatives who are waiting to help me. I know I will be a positive and productive citizen as well as an inspiration to others who might walk my path but won’t if I get one hour of their attention.