As we contemplate various ways to celebrate Black History Month, we must ask ourselves how do we pay proper hommage to this sacred narrative we know as Black History? How do we think and talk about this, the oldest of human histories and about the fathers and mothers of humanity and human civilization who made it? And how do we honor the lives given and the legacy left in and on this long march and movement through African and human history?

The answer to these questions lies in our understanding our history and history itself, its essential meaning, message and forward motion. Achieving this, we approach its celebration not simply as an episodic engagement, but rather as an ongoing process of remembering, studying and practice which aids and grounds our self-understanding and self-assertion in the world and honors the legacy left by those who worked, struggled and made the sacrifice we see as movements, miracles and mighty wonders in our history.

At the heart of the meaning, message and forward motion of history is the practice and promise of struggle. It is an ongoing struggle to be free and flourish as social and natural beings in the world, to know the world and to cooperatively create and enjoy the common good of it, and to always be responsible and responsive in our approach to life and living with others. Thus, to honor our sacred heritage, to bear the burden and glory of our history, we must self-consciously resume our vanguard role in the midst of the liberation struggles of the world.

It is here that the sacred teachings of our ancestors found in the Odu Ifa become so clear and compelling. For the Odu teaches us that we are divinely chosen to bring good in the world and that this is the fundamental mission and meaning in human life. Thus, we must self-consciously become and be fathers, mothers, midwives and mentors who constantly give birth to and facilitate the coming into being of good in the world and who sustain and increase it in the interest of the people and well-being of the world.

So let us continue and expand our struggle and put an end to the oppressors’ illusion about the end of history, the final dispiriting and pacification of the people and Borg-inspired contentions that all resistance is futile. Indeed, we must always find ourselves in the ranks of resistance, alongside the peoples of the world—in Haiti, Africa, Palestine, Iraq, Cuba, Venezuela, Bolivia, Afghanistan and other sites of struggles and paths which open on a new history of humankind.

To achieve this urgent objective, we must first reaffirm our social justice tradition by reviving and expanding its ethical discourse on such issues as freedom, justice, power of the masses, and peace in the world. And as Malcolm taught, we must craft a logic and language of liberation that not only reaffirms our social justice tradition, but also draws a clear line of distinction between us and our oppressor. Moreover, it must disassociate us from and give us firm ground to criticize and confront those Africans and others in service and support of the rulers of this country and the oppressors of the world. This means reaffirming the right of resistance of oppressed people everywhere and rejecting any attempts to give an oppressor equal or greater status than the oppressed or to call on the oppressed to justify their relentless and rightful resistance to occupation, conquest or any other form of oppression. We must constantly reaffirm the right and responsibility to rebel and resist evil, injustice and oppression everywhere. And we must stand strong against advice to collaborate in our own oppression or in the oppression of others actively or passively. For there is no neutral ground in the context of oppression.

Secondly and again, we must stand in steadfast and defiant solidarity with the oppressed, suffering and struggling peoples of the world. This is central, even indispensable, to our social justice and liberation tradition and thus to our self-understanding and self-assertion in the world. Our oppressor cannot be our teacher, or advisor, or the selector of our friends and enemies. This is the meaning of President Nelson Mandela’s defiant and justified embrace of President Yasser Arafat and the Palestinian people who supported the South African struggles and other African liberation struggles when others called them and the Palestinians terrorists, and of President Castro and the Cuban people who helped open the way to South African liberation in decisive battle when the right wing was ranting about communism and trying to curtail the relationship.

It is also the meaning of Congresswoman Maxine Waters’ rejection of the U.S. overthrow of the legitimate and democratically-elected government of Haiti, and her retrieval and return of President Jean Bertrand Aristide to the Caribbean from a U.S. forced exile in the Central African Republic. And it is also a lesson of Harry Belafonte’s criticism in Venezuela of the U.S.’ terrorism and banditry around the world. In standing in active solidarity with the oppressed and struggling peoples of the world we can, in the tradition of Fanon, pose and pursue a new paradigm of how humans ought to live and relate in the world.

Finally, we not only must rebuild the movement, indeed, we must rebuild simultaneously three movements that transform into one movement for a new history of humankind. The first movement is the Black liberation movement, local in grounding and pan-African in scope and ultimate practice. Secondly, we must build a Third World movement which constantly searches for and builds on common ground with the peoples of color of the world. And finally, we must build a progressive movement of committed peoples in this country and the world in the ongoing and common struggle to secure and expand the realm of human freedom and human flourishing in the world.

This month, moment and each day, we are always and ever-standing at the crossroads of history with our foremother Harriet Tubman. We are there when she chooses freedom over enslavement, defense of our dignity over daily degradation, active resistance to oppression over passive acceptance of it. And we are there too with her each day as she self-consciously chooses to understand and approach freedom, not as individual escape or personal license, but as collective liberation, as a practice of self-determination in and for community. It’s these choices and the struggles they inspire and sustain that are the hub and hinge on which African and human history turn. And likewise, they are the root and reason of the celebrations and commemorations we engage in this month and all year.

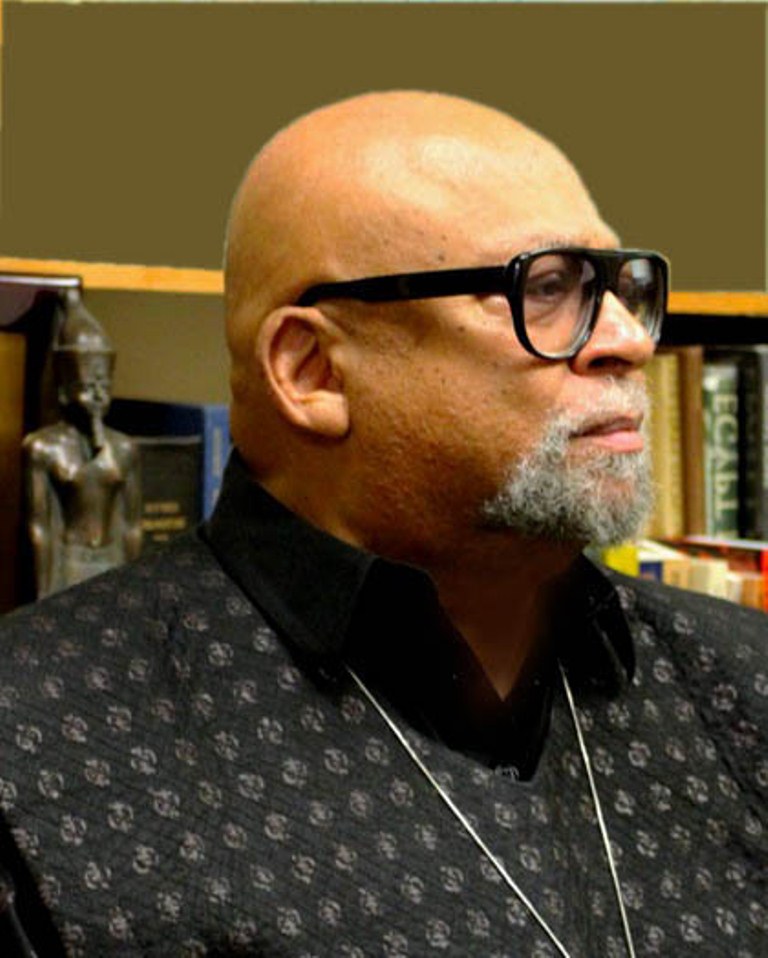

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family,Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org;www.MaulanaKarenga.org.