In the midst of the current state of the world with all its faces and forces of genocide, injustice, evil and oppression, I reach back in the practice of sankofa to retrieve and bring forth the timeless ancient ethical wisdom of our honored ancestors.

And I do this realizing the awesome unequal suffering of women and children in this month and moment of history and in honor of their defiant and radical refusal to be defeated, to be resigned in despair or to cease their resistance in opposition to oppression and in affirmation of their dignity, humanity and indispensable role of sustaining, shaping and bringing good in the world.

As we close out this month of celebration, commemoration, and meditation in special and rightful homage to African women and to women as a whole, it is important to reaffirm our continuing commitment to respecting and securing the equal dignity and rights of women, and to reflect on the awesome meaning and indispensable role of women in co-creating, restoring and sustaining the world. And for us, as a people, this reflection is best centered and pursued within the framework of our own culture and in the context of our own times.

It is indeed a time when we are called and morally obligated to recognize the precarious state of the world characterized by processes and practices that disrupt, endanger, and degrade both our social and natural worlds which are interlinked and mutually determining, and to appreciate the ever-present urgency to engage these problems and develop ethical and effective ways to restore and sustain the world.

As Nana Dr. Wangari Maathai, leader of the Green Belt Movement, stated in her Nobel Peace Prize lecture, “Today we are faced with a challenge that calls for a shift in our thinking so that humanity stops threatening its life-support system. We are called to assist the Earth to heal her wounds and in the process heal our own.”

Surely, there is an urgent need to respond in rightful and productive ways to is-sues of justice in society and between peoples of the world; plunder, pollution, and depletion of the environment; natural and human-made disasters; structured and persistent poverty; the awesome ruin and waste of war to people and the natural world; the unequal burdens on women and children; and the profound concern for the interests of future generations.

It is important to note that our ancient ancestors raised the question of sustaining the world as an ethical obligation in the earliest of times. It develops as a discourse and moral duty in the ethical imperative of serudj ta, to repair, remake and renew the world, found in the Husia and evolves in the Odu Ifa as an explicit and specific responsibility for women, with the implicit under-standing of a shared responsibility with men.

The Odu Ifa, reaffirms this shared divine status and world-encompassing responsibility of women and men to sustain the world. But it explicitly assigns women the role as sustainers of the world, again with the implicit understanding that men are co-creators and co-sustainers with them. The central source of the ethical concept of women as sustainers of the world is Odu 10:2 and is developed in the narrative of creation.

As the narrative unfolds, three orisha (divine spirits) Odu, Obarisa and Ogun are sent from heaven into the world. Odu, the female orisha, which symbolizes women in the world, turns around and returns to ask Olodumare, the Creator, two essential questions, and the answer to each defines the central tasks and responsibility of women in the world.

When Odu asks what is to be done in the world, Olodumare, Lord of Heaven, assigns women to be co-creators of a good world with men. And the text says he gave both women and men the ase (ashe), the divine power and authority, to do what they needed to make the world dara, good, i.e., beneficial, and beautiful. When Odu asks what is her particular power within the assignment of co-creator of the world, Olodumare says, “You will be their mother forever and you will also sustain the world.”

It is important to note here that these assignments are world-encompassing assignments. Thus, Odu is assigned not only to be the mother of the orisha, but also mother of the world, even as she is to be sustainer of the world.

The text tells us he also gave Odu a great spiritual power and “the ase so that whatever men wanted to do, they could not possibly create anything, if they excluded women.” The use of the word create (dá) refers to the assignment of co-creation of the world and reaffirms the indispensability of women in all things of importance and value in and for the world. It finds its parallel text and reaffirmation in Odu 248:1 in which Olodumare commanded the due respect for the presence, power and effective participation of the female orisha, Oshun, divine spirit of culture, learning and human flourishing for successful deliberations and work of creation.

Here we are reminded of Nana Dr. Anna Julia Cooper’s contention that the eventual triumph of women’s rights will at the same time signal “the final triumph of all rights over might, the supremacy of the moral forces of reason, justice, and love in the government of the nation” and by extension, in the nations of the world.

The three world-encompassing roles and responsibilities divinely assigned to women in the Odu Ifa are interrelated and flow from the identity of all humans as eniyan, chosen ones, those divinely chosen to bring good in the world. It is within the context of our collective vocation of bringing good in the world, then, that the additional and particular aspect of women’s vocation of mother of the world and sustainer of the world emerge.

Thus, to be co-creator is to bring good in the world. To be mother of the world, in the bio-social sense, is to co-create spiritually and ethically grounded human beings, to nurture, teach, protect, mentor and advise on various levels and in various venues, ultimately including the whole world.

And to sustain the world, as the phrase “mu ilé ayé ro” suggests, is to literally make the world stand upright, i.e., ensure that it is good, secure and endures. In Odu 78:1 and other chapters, this dual emphasis on well-being and right-being requires among other things: the quest for and ethical application of knowledge; the struggle for justice; the cultivation of character; the pursuit of peace; and active concern and care for the earth.

It is within this overarching concern for humanity and the world that Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune, great and honored educator, institution-builder, and activist, teaches us that to sustain the world, “We must re-make the world. The task is nothing less than that.”

And she reminds us in this earnest striving and struggle that “the task that is before us as human beings cannot be accomplished singly,” that is to say by one race, gender, class, religion or nation. On the contrary, she says, “we must live together; we must work together. We must be willing to use the great measuring rod of justice and fellowship to (humankind) for the sake of (humankind) everywhere” and thus, for the world.

————————————————————————————————————-

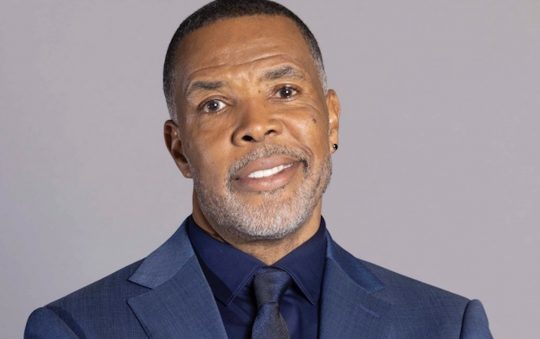

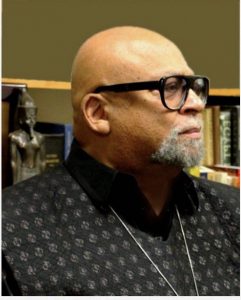

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.MaulanaKarenga.org; www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.Us-Organization.org.

Want more Black news? Join the community today! Click here for the Weekly newspaper and E-paper.