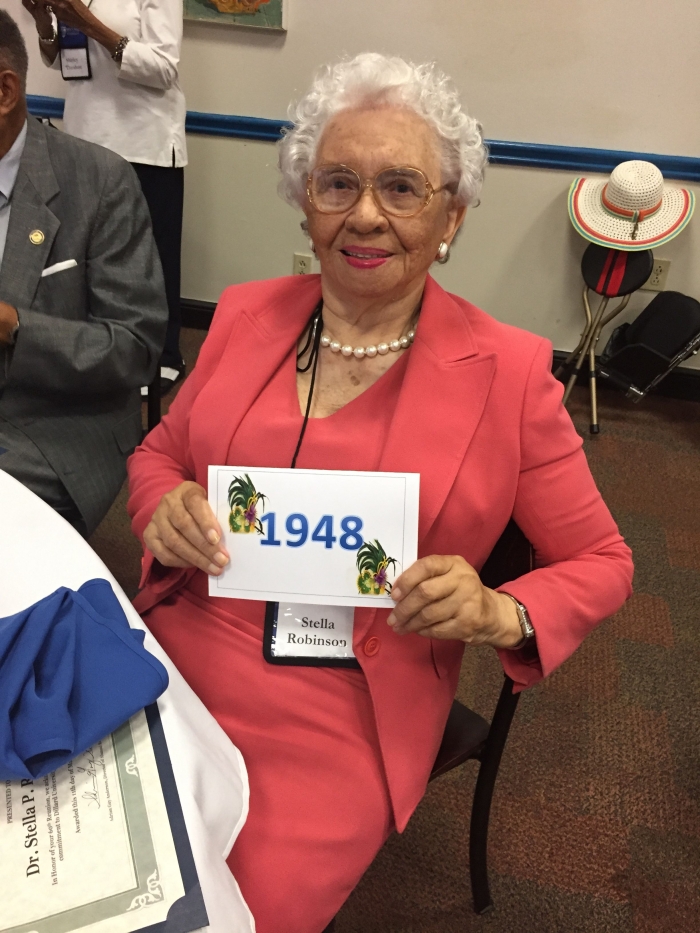

Stella Pecot Robinson, RN, PhD, is older than the Los Angeles Sentinel, and she will soon – on August 25th — be 100 years of age.

Like a nearly 90-year-old newspaper, the breadth of stories she’s accumulated over a lifetime is substantial and distinctly rich. The recurrent themes: seize opportunity, and never stop learning.

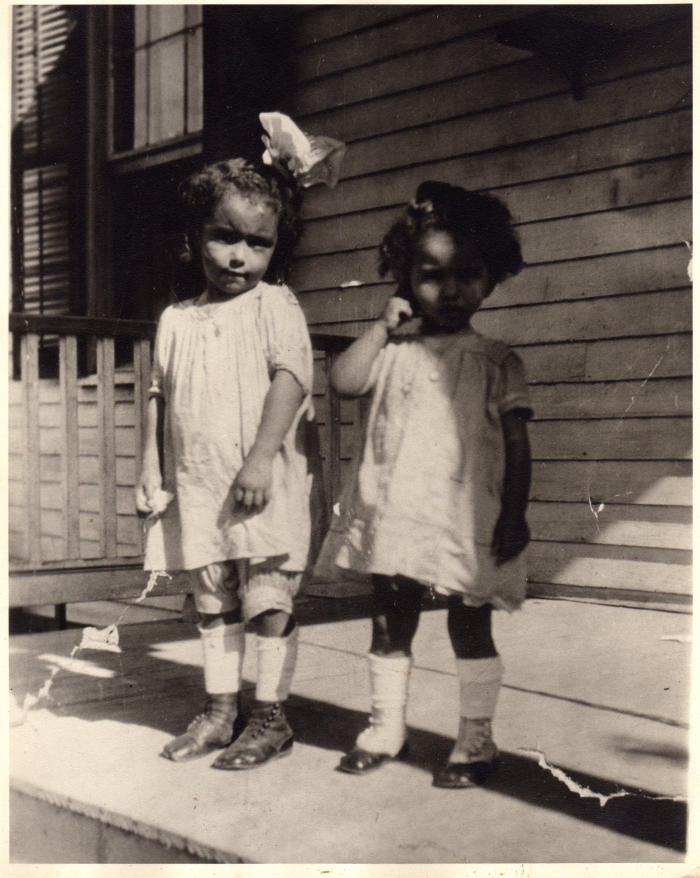

Born in rural Louisiana in 1922, Robinson learned early about the value and impact of community and generosity as she observed her mother raise her own five children during the Great Depression, in addition to Stella’s two young uncles, after the passing of her father.

“Mama helped other people if they needed help with something,” Robinson remembers. “And people in turn would come by and tell her they went fishing, and ‘how many fish do you want,’ [or] ‘I went hunting, how many rabbits do you want,’ so people shared, and that helped as far as running the family was concerned.”

Quite possibly, the foundation for a help-centered and health-oriented career like nursing was laid during those formative years, and later, when the United States Nursing Corp set about recruiting people to enroll in the military, offering free room, board, tuition, and a monthly $20 stipend, it didn’t take Robinson long to sign up.

“It was a very good decision,” she reflected. “Fortunately, World War II ended in 1945 when I graduated, so I never had to do any military service. And it turned out that I have enjoyed the career in nursing.”

She’d been well prepared for this emergent opportunity, as prior to this, Dr. Robinson attended Gilbert Academy, a prestigious secondary school, and went on to enroll at the HBCU Dillard University. Absorbing all she could related to nursing, Dr. Robinson graduated magna cum laude. During this time, she would also undergo a political awakening and advocated for voter education and registration at a time when Black women were not allowed to vote. Next, she earned a Master’s degree from Columbia University Teachers’ College.

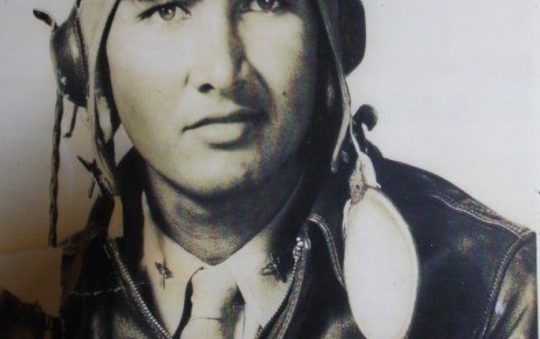

Upon marrying, Robinson moved to Hawaii with her husband, where he chose to work because the Civil Aviation Agency would not hire Black people in the continental United States. That bitter pill sweetened, as it was there that she and a colleague set up an innovation for teaching pediatrics and maternal health for a nursing program at the University of Hawaii that resulted in its students scoring higher on the state board exam than anyone in continental U.S.

“After they graduated scoring so high, [the state board] contacted the chairperson at the University of Hawaii and wanted to know who had taught them,” said Robinson.

The two were asked to go to New York and serve as consultants, which Stella managed to do while nursing an infant and rearing two older children. From there, her husband’s work brought the family to Oklahoma. And as she’s done throughout her life, Stella would seem to hit a milestone and make her mark wherever she landed on the map.

Navigating decades of incremental progress for Black people in America, Robinson dealt with a myriad of signature race-specific experiences like being overqualified for a job for which she endured excessive interviewing processes along with indignities like not even being able to meet with the prospective employers onsite. This occurred at Oklahoma Baptist University. For the record, she got the job.

She was often encouraged in her earlier years to pass for White as some of her peers and relatives were inclined to do. “I was never prompted to pass,” Robinson said, speaking to her personal inclinations, then sharing the sage words of landlords she once encountered in Chicago: “They felt Black people needed to stay Black, and whatever contributions they made would be made as they were.”

Robinson also cooked, cleaned houses, and served as chaperone for younger co-eds to pay her way through school at Gilbert Academy. While there, she was taught by a gracious English teacher to speak using proper grammar, this adjustment being another hallmark of Black life in those times.

On a visit home one weekend, Robinson recalls her mother and a friend listening to her diction answering the telephone: “I heard the lady say, ‘how come that girl talks so funny?’” Her mother’s answer: “I don’t know; she’s been talking like that ever since she went to that school.”

All the while, Robinson’s grades were exemplary, and this led her to receive scholarships throughout her academic career, including a Rockefeller Scholarship at Columbia University, which has since inducted her into the Nursing Hall of Fame for Nursing Education.

Growing up in a rural southern area like Franklin, Louisiana at the height of segregation, Robinson had always heard that going north, east, or west would be better. Her journey has taken her in each of those directions, where she found “it was pretty bad in other parts of the country, too,” but she ultimately was convinced, with some help from her husband, a native, to make Los Angeles her home.

Hired by Los Angeles County Hospital School of Nursing, she was the first Black instructor to teach in a registered nursing program in the State of California.

The seeds of community activism that were sown at Dillard University in the 1940s blossomed further in the 1960s when Athens Tank Farm, which was located at the current site of Magic Johnson Park, proposed to put 1,000 units of low-income housing in a remarkably small area of land.

“There would be approximately 3,000 children, and there was no permission for a school,” Robinson remembers. “It was a mess.”

“She began organizing the community and holding meetings at Bel-Vue Presbyterian Church, having, at times, 200 people from the community at either the County Board of Supervisors or County Commission meetings,” her daughter, Dr. Deborah Robinson, recalled.

Ultimately, she earned her doctorate in 1984 in Adult Education with a specialty in gerontology at the University of Southern Mississippi, learning that, out of 100 people taking the entrance exam, she scored the highest—and she was the only Black student who tested. And she was 62-years-old at the time.

Looking back, one of Dr. Robinson’s early memories of venturing beyond her hometown is one that well sums up her character. “When I went to Gilbert Academy …and they took me to the library, there were three rooms of library books – I had never known there were that many books in the world, so I asked how you get to use these books,” she reflected.

“They said just check them out. Black people couldn’t go to the library in Franklin, so I didn’t know that’s how libraries work, so I started checking out two books at a time, reading them and turning them in – I thought they might change their mind.” Those feverishly read books figuratively represent the many achievements, milestones, and experiences she has packed into a lifetime.

The lists of boards, committees, councils and commissions Dr. Robinson has sat on, is hefty, to say the least. President Kennedy appointed her to the Equal Opportunity Advisory Committee. She helped establish the Charles R. Drew Postgraduate Medical School and the nursing program at Alcorn University.

She served on the Black Education Commission of LAUSD, all the while, maintaining leadership positions in local community organizations like Boy Scouts, PTA, Block Clubs and at church. In 1976, she was honored for outstanding contributions to the City of Los Angeles by the L.A. Human Relations Commission and LA City Council.

“I’m most proud of being able to teach at various levels,” Dr. Robinson notes. “I’ve taught fundamentals in nursing. I’ve taught medical surgical nursing. I’ve taught graduate students.”

She also taught three children who have achieved a great deal themselves. And she’s taught lessons on longevity just by being interviewed for this article.

“I think nursing encourages people to take care of their health; that’s one big factor,” Stella notes when considering how she’s been able to thrive for one hundred years. “Another is family support.”

Good genes, apparently, are also part of the brew, as several in her lineage lived into their eighties and nineties. While, alas, that component comes down to luck of the draw, a healthy life marked by familial and/or community support is something to which all can aspire.