Charles Matthews

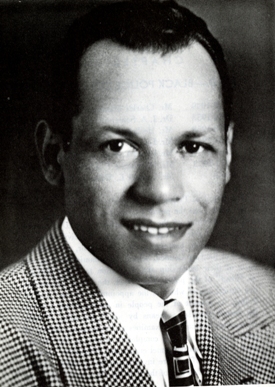

Dr. John A. Somerville

.jpg)

Everette M. Porter

Elbert T. Hudson

Marguerite P. Justice

.jpg)

Samuel L. Williams

Melanie Lomax

David S. Cunningham III

John W. Mack

Â

Legends

By Yussuf J. Simmonds

The Commissioners

“They were the first defense between the LAPD and the Black communityâ€

Â

In the not-too-distant past, the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) was considered an occupying force in the Black community – not that it has totally changed – but substantial progress has been made which has resulted in a simmering of the tensions that have heretofore existed between LAPD and the Black community. Some positive actions have caused the change in the relationship including the structural makeup of the department and its command staff, presently more reflect the diverse makeup of the city; partial implementation of the Christopher Commission recommendations (the inspector general) and the federal consent decree; and a combination of other factors such as community policing and better overall community relations.

Â

The board of commissioners consists of five civilians, appointed by the mayor and approved by the city council. They have the responsibility of regulating and supervising the activities of the LAPD and they maintain respectable oversight over the operation of the department primarily through the police chief. They are the “head†of the police department and are non-salaried volunteers.

Â

Whenever major problems arose in the L.A. Black community and the police are involved, LAPD is often in the frontline of law enforcement activities such as the 1965 and the 1992 (Rodney King) civil unrests, incidents involving the deaths and/or brutality of Ronald T. Stokes, Leonard Deadwyler, Eula Love, Margaret Mitchell, William Rogers, and Stanley Miller, just to name a few. And the Black commissioners have often been lambasted as “sleeping with the enemy†since they are charged with the oversight of the department’s activities. However, much has changed – though there is still much to be done, and Black commissioners have been instrumental in orchestrating some of the changes within the LAPD. Â

CHARLES H. MATTHEWS (1946 to 1950) – He was the first Black police commissioner of the LAPD, appointed to the board by Mayor Fletcher Bowron. Prior to his appointment, Charles Matthews was a deputy district attorney, one of the first African Americans to serve in that capacity from 1931 to around 1945. He prosecuted many highly publicized cases. When Judge Charles W. Fricke, who was the dean of the criminal court trial judges was asked: “Who was the best trial lawyer you ever saw in your courtroom, he instantly replied: ‘Charles Matthews.’â€Â A graduate of UCLA, he was admitted to the California State Bar in 1930 and was in private practice very briefly before entering the DA’s service. Matthews returned to private practice while serving as police commissioner and was also active in civic and community affairs. In private practice, he represented Liberty Savings & Loan Association; was on the board of Golden State Mutual Life Insurance Company; was a panel member of the Los Angeles Civil Service Commission, the National and Criminal Courts Bar Association, and a life member of the NAACP.Â

DR. JOHN A. SOMERVILLE (1949 to 1953) – A dentist by profession, John Somerville worked his way through dental school becoming the first Black graduate of USC, and the examining dentist and advisor to the Los Angeles Draft Board. His academic achievements included an honorary Doctor of Laws degree from Bethune-Cookman College, Florida where he was also a member of the board of trustees while he was a commissioner. He was appointed police commissioner by Mayor Bowron, served as a member of the State Commission on Crime Prevention and was a delegate to the Democratic National Convention in 1936. Somerville was actively involved in the NAACP and served as president of the Los Angeles Chapter and on its national board. In 1953, Queen Elizabeth II named him an honorary officer of the British Empire for his work in furthering Anglo-American relations.  He and his wife, Vada, built the Hotel Somerville in 1928 which later became famous as the Dunbar Hotel, the hub of Black culture and entertainment in L.A. It was built entirely by Black contractors, laborers, and craftsmen, and financed by Black community members.

Â

HERBERT A. GREENWOOD (1953 to 1958) – When Herbert Greenwood was appointed to the police commission by Mayor Norris Poulson, he was the only Black member of the board. (In those days, only one Black, female and/or non-white would be appointed to the board at the same time). He was criticized by the Black press and when he tried to intervene in to stem overt acts of racism, discrimination and police brutality – especially against Blacks – he was stonewalled at every turn. His tenure as a police commissioner was punctuated by police brutality against Blacks and Latinos which led to his resignation and prompted a stern outcry from the L.A. branch of the NAACP via a telegram that stated in part: “…unfair and brutal treatment of Negroes and Mexicans at the hands of Los Angeles policemen urge a thorough investigation of the charges of police brutality and discrimination made by former Police Commissioner Herbert Greenwood…â€Â Not surprisingly, his tenure coincided with the beginning of Chief William Parker’s notorious reign.

Â

EVERTTE M. PORTER (1961 to 1963) – Everette Porter came to Los Angeles from Louisiana at an early age and after attending Polytechnic High School, he went to Chapman and Southwestern University where he earned his law degree and he also did graduate work in political science at Cal. State L.A. Porter was admitted to the California State Bar in 1941, and entered private practice prior to serving in the U.S. military. During World War II, he distinguished himself and rose to the rank of captain for which he was awarded the Bronze Star for service above and beyond the call of duty. After his military service, he resumed private practice and in 1955, he was appointed to the California Adult Authority (parole board). Six years later, Mayor Sam Yorty appointed Porter as a police commissioner; he eventually became vice-president of the commission. Though his tenure was relatively brief, his exemplary work there was instrumental in facilitating his rise to become commissioner and Judge Pro Tempore of the Los Angeles Superior Court. While on the bench, Porter was active in the county’s Lawyer’s Club and Bar Association where he had a major impact in the Family Law Section. Local church groups felt beholden to him and honored him for efforts in keeping families together.      Â

Â

ELBERT T. HUDSON (1963 to 1970) – Elbert Hudson was a police commissioner during one of the most devastating periods in the history of Los Angeles; the 1965 Watts Revolt. He was appointed by Mayor Sam Yorty to the police commission. Hudson migrated from Louisiana and was very involved in civic and community affairs in the Los Angeles area as a lawyer, a probation officer, a banker and member of the boards of the NAACP and Golden State Mutual Life Insurance. During World War II, he was attached to the legendary 332nd Fighter Group better known as the Tuskegee Airmen. Returning to civilian life, he started off as a deputy probation officer while attending law school. After graduation, Hudson began private practice, earned a banking credential, and became president/CEO, and eventually chairman of Broadway Federal Savings and Loan Association, the bank founded by his father, Dr. H. Claude Hudson. Amidst his multi-faceted career, he served as a police commissioner, and shared his talent and expertise to assist businesses and organizations in the community including the Brotherhood Crusade where he was a board member. His life experiences included the Great Depression, World War II, the Korean War and the Civil Rights Movement. Hudson was referred to as a drum major for justice. Â

MARGUERITE P. JUSTICE (1971 to 1972) – Marguerite Justice was the first Black woman to serve as a police commissioner, not only in the LAPD but in the United States. A longtime community activist from southwest Los Angeles, she was known as ‘Mama J. and was appointed to the police commission in 1971 by Mayor Sam Yorty. At the time of her appointment, she was the second woman to be so appointed and said that women could bring greater sensitivity to police oversight because they think with their hearts. Time and circumstances may have proven her to be correct because many law-enforcement observers have come to believe that to be correct. Justice went on to say later on, “I’m Black. Therefore my sensitivities already extend to minorities. I’m not rich and so my sensitivities also extend to the poor and oppressed. I know what’s happening at a grass-root level but the sensitivity I refer to should be for all people.â€Â Her experiences as a Black female police commissioner triggered an episode of the “Adam-12†series and she made tremendous efforts to bring about change within the department especially relative to Black and Latino officers. Her efforts continued after she left the commission. A support group she had founded in 1969 set up a round-the-clock hospitality house for police officers during the 1984 Los Angeles Olympics. Justice migrated from Louisiana and lived much of her life in Southwest L.A. where she devoted most of her time doing volunteer work.

SAMUEL L. WILLIAMS (1973 to 1991) – Samuel “Sam†Williams was one of Mayor Thomas Bradley’s first appointments to the police commission and he was well known in the legal community having been described as a mentor to several prominent jurists, attorneys and was a deputy attorney general for the California Department of Justice in Los Angeles. In addition, he became the first Black president of the LA County Bar Association, the California State Bar and of the police commission. He received academic and athletic scholarships to UC Berkeley and also attended USC Law School. Williams was the staff attorney for the McCone Commission, which investigated the 1965 Watts Revolt and sat on the boards of Walt Disney, the LA Chamber of Commerce and the LA Music Center. He was reported to have passed up appointments to the State Supreme Court and the federal bench both for family reasons. He served in the U.S. Army in the military and developed an interest in criminology that led him to become a probation officer. However, it was his recognizing the tremendous gulf between the perspectives of a probation officer versus that of the legal system which propelled him to become an attorney. As a trailblazer in the legal field and a member of the prestigious law firm of Beardsley, Hufstedler and Kemble, Williams pioneered the way for a generation of African Americans to enter the legal profession, succeeding in their own law firms and/or landing plum positions in large law firms. His legacy transcends the legal community and reaches beyond to the community as a whole. In 1979, he was honored by the Brotherhood Crusade as a legal pioneer and has left enormous footprints that have remained imprinted in the sands of time. Having served as one of the longest commissioners on the board, he resigned in 1991 in the wake of the Christopher Commission’s findings after the Rodney King beating.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Â

Â

Â

MELANIE LOMAX (1990 to 1991) – When Mayor Thomas Bradley appointed Melanie Lomax to the police commission, it was the first time that the board had two Black commissioners at the same time. She was an established civil rights lawyer having gained a reputation in the Los Angeles County Counsel’s office defending county agencies in labor and civil matters where she had begun in 1975. She graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, and Loyola Law School in Los Angeles eventually founded her own law firm in 1984 specializing in age, sex and racial discrimination cases. Lomax was the president of the police commission – the first Black woman to attain that position – when motorist Rodney King was beaten by four LAPD officers which eventually triggered one of the worst incidents of civil unrest in the nation.  Afterwards she waged a tireless battle, as commission’s president, to oust the then police chief and to transform the department’s culture. When she was not successful, Lomax tendered her resignation, returned to her law practice and continued her efforts to change the LAPD and served as vice-president and general counsel of the local NAACP. She publicly admonished some Black Hollywood entertainers for not giving back enough to the Black community who, she said, was the source of much of their wealth and success. Lomax died mysteriously in 2006 when her car plummeted down an embankment near her home in Hollywood Hills.

Â

JESSE A. BREWER (1991 to 1993) – Jesse Brewer had the distinction of being the highest-ranking African American – assistant police chief – in the LAPD when he retired. Called as a witness during the Christopher Commission’s investigation in the wake of the Rodney King incident, Brewer criticized the police chief under whom he was the assistant chief. After his testimony to the Christopher Commission, Mayor Thomas Bradley appointed him to the police commission. Prior to his confirmation by the city council, Brewer was asked by a reporter, how he would get along with his old boss – since being a commissioner would place him over the chief. He said, “The only thing I can say is that Chief Gates and I have been very close for three years. We work very well together, very cooperatively.â€Â Brewer’s knowledge and experience in the LAPD department made him a valuable appointee to the commission at a critical time in the department’s history. Before being an officer in the LAPD, Brewer was attached to the Chicago Police Department. At one time during his tenure at LAPD, he was in charge of the SWAT team whose exploits were a weekly television series. He served on a presidential commission on organized crime and was a technical adviser to the television show “Hill Street Blues.” In memory of his work in the department, the 77th Street Police Station was renamed the Jesse A. Brewer Station and also the city of Los Angeles has named a park in his honor. Â

Â

DAVID S. CUNNINGHAM III (2001 to 2005) – David Cunningham III began his legal career with the Department of Justice’s honor program and clerked for U.S. District Court Judge, Terry J. Hatter, Jr., where he researched a wide range of federal issues. He graduated summa cum laude from USC and attended New York University School of Law where he was a founding member of the law school’s Public Interest Law Foundation – a student organization designed to fund entry-level positions for attorneys interested in serving the public interest. As a lawyer, Cunningham has chalked up over three decades of distinguished service in the community, working in the public and private sectors. In 2001, Mayor James Hahn appointed him to police commission where he served as its vice president and eventually became its president. While on the commission, he dealt with several high-profile issues regarding police shootings and the use of excessive force, and worked to institute changes in the department’s policies as they relate to proper policing and good community relations. Described by his colleagues as an individual with a great judicial temperament, Cunningham was recently appointed to the Los Angeles Superior Court by Governor Arnold Schwarzenegger and his father, a former Los Angeles City Councilman David Cunningham, Jr., said of the appointment, “I’m really honored by his appointment; I really believe that he will be a very excellent judge. He has always had the judicious attitude about his approach to decision-making. He’s always been a lover of the law and a number one student of the law. So I’m really proud as any father would be.â€Â Court observers have said that it is not difficult to predict the quality of Cunningham’s judgeship; he has had a sterling legal background since graduating from law school.

Â

JOHN W. MACK (2005 to the present) – For three decades, John Mack was synonymous with the Los Angeles Urban League (LAUL); he was the face of the Urban League in L.A. He made it into one of the most successful community organizations in L.A. Under his leadership, the LAUL served over 100,000 individuals a year as it operated job-training and placements; education, tutorial and youth achievement programs; art computer technology preparation; and a number of academic and employment innovated programs which focused on serving African Americans and other people of color. After he retired, Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa appointed him to the police commission in 2005 where he has served as its vice president and also its president. Mack has been an advocate for equal opportunities since his days as a student leader in the 1960’s Civil Rights Movement in Atlanta. He holds a Bachelor’s degree from North Carolina A& T State University and a Master’s degree from Clark University, Atlanta. In 2006, he was awarded an honorary Doctorate of Management degree from the Claremont Graduate University School of Education. Throughout his career at the Urban League, Mack has been an advocate for equal opportunities in education, law enforcement and economic empowerment for African Americans and other minorities, and he is considered a bridge builder across racial, cultural, economic, gender and religious lines. In addition, he has served as a teaching fellow in residence at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government Institute of Politics, and has received numerous honors including the Magic Johnson Foundation Humanitarian Spirit Award; the LAUL’s Whitney M. Young, Jr. award; the SCLC Martin Luther King, Jr. President’s award; the Los Angeles NAACP’s Lifetime Achievement award; the Thurgood Marshall Fund award; and the L.A. Board of Education has named the “John W. Mack Elementary School†in his honor. Â

Â