Part 1. It is an often repeated Kawaida contention that “This is our duty: to know our past and honor it; to engage our present and improve it; and to imagine a whole new future and forge it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.” It is an affirmation of our firm belief that we can always find our way forward in our history by studying it thoroughly, learning its best lessons, grasping its most instructive insights and using this knowledge and understanding to engage the critical issues of our time; and imagine and forge a future worthy of the name and history African.

This month, July, marks the 50th anniversary of the Newark (July 12-17) and Detroit (July 23-27) Revolts, and the first National Black Power Conference (July 20-23), 1967. The revolts and the conference which sought to raise up the spirit of revolt and resistance encouraged us to plan and put in motion an agenda to realize Black Power in intensified struggle, relentless organization and seizing political power. Since 1965 in the wake of the assassination and martyrdom of Malcolm X and the August Revolt (August 11-16) in Los Angeles (Watts), our organization Us had been engaged in the lifting up and advancing Malcolm’s legacy, raising up the spirit and practice of revolt and building toward the historic period of the Black Freedom Movement called Black Power.

As a culturally-grounded, people-focused, revolutionary organization, Us began its mission and work in an era of global, radical and revolutionary change. The world was on fire with the forward movement of the Third World masses in righteous revolt and revolution. And, as Malcolm taught, we saw ourselves and our people as part and parcel of this awesome global struggle between the oppressed and the oppressor.

There was in the post-revolt era a widespread sense of oncoming victory. We of the emerging Black Power Movement went to bed late and woke up early discussing and debating the burning issues and ideas of the day: i.e., the meaning and motion of history, race and racism, revolt and revolution, cultural and political revolution, nation and class, self-determination, armed struggle, national liberation, Black Power, Black art, Black theology, Pan-Africanism, socialism, capitalism, colonialism, imperialism, Third World solidarity and modes of educating, mobilizing and organizating for struggle and nation-building. There was talk also, following Malcolm, of our being “a nation within a nation”, an internal colony, suppressed by an occupying army called police in our community, and the need to control and end their violence. And we established a Community Alert Patrol in 1965 to follow, monitor and gather evidence of their pattern of practice, and organized a group of pro-bono lawyers to teach people their rights and their informed responses and intervened where possible to prevent or halt unchecked official violence.

We strove both to understand the world and change it. We began as mostly students, but our schools, colleges and universities and the books and interpretations they offered, were too limited for anything but references to refute and assumptions and contentious to mercilessly take apart and expose as oppressive in concept and practice. And we dared to replace their enslaving and oppressive language and logic with a language and logic of liberation, deep and liberating ways of thinking and asserting ourselves in the world.

Kawaida philosophy was born in these intellectual conversations and struggle, nurtured and grounded in the womb of the work we did and the struggles we waged to serve our people and achieve with them their own liberation. We sought to create a culture of struggle thru a cultural revolution, rejecting the culture of oppression and reaching back and deep within our own ancient and current history and culture for paradigms of African ways to understand and assert ourselves in liberating and liberated ways.

Five decades and half a century later, Us and Kawaida philosophy are still engaged in the work that brought us into being and gave and continues to give meaning and motion to our lives. It is none other than the work and struggle to define, defend and advance the interests of our people while at the same time being committed to the good of humanity and the well-being of the world.

It was in the context of the struggle for Black Power that Us came into being, authors and heirs of the revolt and reaffirmation of the 60’s. And it is Malcolm that first taught us the need for Black Power. Speaking from within the nation-building context of the Nation of Islam, Malcolm gave us this lesson in the need for power. He said that we cannot expect voluntary moral behavior from an immoral and amoral system which worships and only speaks in terms of power. Moreover, he said to us in 1964, “You’ve got to get some power before you can be yourself, once you get some power and you be yourself, you can create a new society and make some heaven right here on earth”. Thus, to free ourselves we must be ourselves and then build the good world we all want and deserve.

Malcolm made us in Us think deeply about not only the need for power to determine our destiny and daily lives, but also the ethics of the pursuit and possession of power. In other words, we saw in Malcolm’s teaching and in our discussion of the conditions of deprivation and oppression which our people suffered, that it was immoral to deprive persons and people of power over their destiny and daily lives. And thus, it was ethical, indeed, a moral obligation to struggle to achieve that power in the interests and name of our people.

Rep. Adam Clayton Powell of New York is a second major source for the evolution of the idea and movement of Black Power. In a commencement address at Howard University, May, 1966, he framed Black Power, like Malcolm, in the context of the struggle for human rights. He stated that “Human rights are God-given rights. Our life must be purposed to implement human rights…to demand these God-given rights is to seek power”. Kwame Ture heard these words and discussed the meanings and implications of them with Rep. Powell and later he would raise the cry of Black Power himself and make it a household word. Later, in August 1966, Rep. Powell called a meeting of leaders from around the country, including Maulana Karenga, to come to a summit to discuss how we might pursue Black Power as a political goal and practice. This would lead to a formation of a Continuations Committee and the holding of the first and second National Black Power Conferences.

Certainly, the third and most known source identified with Black Power is Kwame Ture of the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), who raised the issue of Black Power in Greenwood, Mississippi in June of 1966. In this speech, he said “We’ve been saying ‘freedom now’ for six years and we ain’t got nothing. What we gonna start saying now is ‘Black Power’.” Later, he defined Black Power as “a call for Black people to unite, to recognize their heritage, to build a sense of community, to define their own goals, (and to lead their own organizations).”

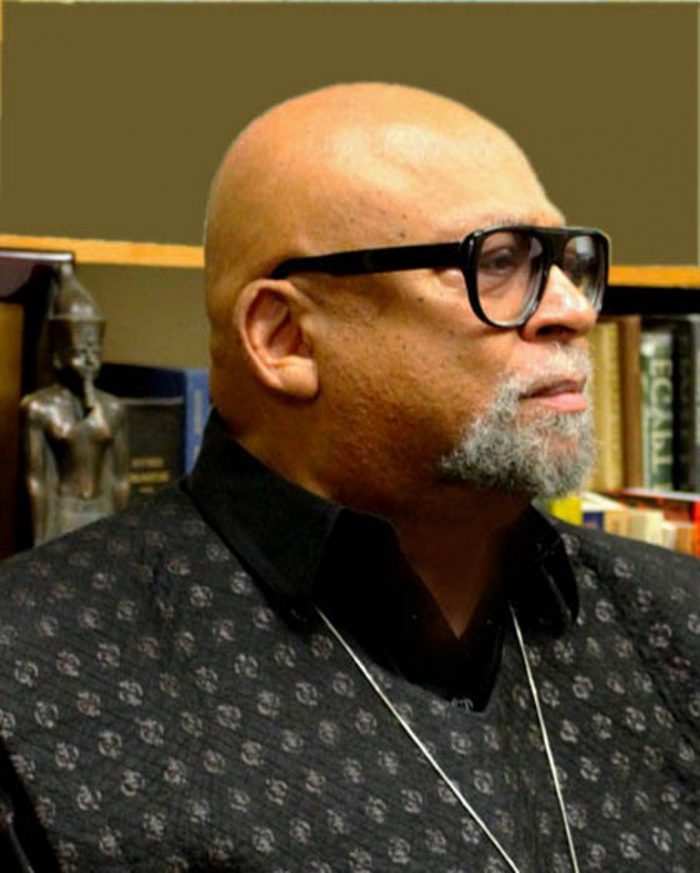

A fourth source of Black Power discourse and practice is Maulana Karenga and the organization Us. Maulana Karenga, speaking on behalf of the organization Us, challenged a new generation to join in struggle for Black Power which he defined as “the collective struggle of Black people to achieve three fundamental aims: self-determination, self-respect and self-defense.” He had used this same definition to define revolt in August 1965, but with the rise of Black Power, he interpreted the struggle for Black Power as an ongoing revolt for self-determination, self-respect and self-defense.