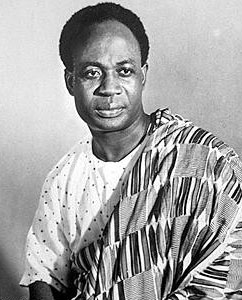

Dr. Kwame Nkrumah

Nkrumah with the Father of the American Civil Rights Movement

The Big Six–Fathers of Africa’s independence movements

(Osageyfo) Dr. Kwame Nkrumah

FATHER of Ghana’s independence & indeed the continent of Africa

GENERAL OVERVIEW OF COLONIAL AFRICA

When Kwame Nkrumah was born, Ghana was called the Gold Coast and it was so named because the western coast of Africa, where it’s located, was/is laden with gold. Its ancient history is enshrouded in myth and legend, and little is known about that area of the world. However, Nkrumah has brought Ghana to the forefront of modern African history as he is the foremost proponent of Pan Africanism in the latter half of the 20th century and the father of Africa’s modern day independent movements. The decolonization of Africa began with Nkrumah in Gold Coast, British West Africa, which was the home to some of the continent’s earliest nationalist movements. He led the Gold Coast’s drive for independence from Britain and presided over its emergence as the new nation of Ghana–first as prime minister and then as president.

During the period of European colonization of Africa, Nkrumah emerged as the beacon of hope and inspiration to counter the never-ending stream of White dominance over the people of color worldwide. He knew that once started, independent movements would eventually sweep the continent, however, one of the factors he was unable to control was the “quality” of the new independent governmental structures. Most of the new African nations inherited European forms of government–the same structures that had oppressed them–with a parliamentary system including a legislature, competing political parties and a prime minister chosen by the legislature rather than directly by the people. In addition, many of the new African leaders received their training–their education–in Europe and the United States (U.S.), training from the same people who colonized them. Hence, many post-independent African leaders were mirror-images of the oppressors/colonizers. (Besides Nkrumah, some of the notable exceptions included Patrice Lumumba, Gamal Nasser, Jomo Kenyatta, Robert Mugabe and Nelson Mandela even though remnants of centuries of colonization, oppression and apartheid cannot be eradicated overnight; it will take centuries to undo what the evil colonizers and neo-colonizers did and are still doing).

HIS EARLY YEARS AND EDUCATION IN THE UNITED STATES

Born Nwia Kofi Ngonloma in 1909 in Nkroful, Southwestern Gold Coast, Nkrumah came from a modest, traditional family; his father was a gold smith. He attended catholic mission schools and at the Achimota grammar school, and eventually became a schoolteacher at a Catholic school primarily in Axim. Because of the scarcity of trained teachers, Nkrumah also became a “roving” teacher–teaching elementary schools in towns and villages along the coast. He was very popular and charismatic, and earned a decent living as a teacher. He met a few influential figures, who aroused his curiosity and sparked his interest in politics.

He left Gold Coast around 1935 bound for the U.S. to continue his schooling. Nkrumah reached New York and became acutely aware of the politics of race relations, plunging heavily into America’s Black communities, especially Harlem. Assisted by a small scholarship, he enrolled at Lincoln University (America’s oldest Black university) where he earned a bachelor’s degree in Education. He then earned a master’s degree in Philosophy at the University of Pennsylvania. During the summers, Nkrumah worked at physically demanding jobs in the shipyards and in construction to supplement his scholarship. He forged lasting ties with C. L. R. James from Trinidad and other Black Americans; frequented Black churches in New York and Philadelphia; and gleaned from those experiences, alternatives to the British colonial rule in his native land. Though Marcus Garvey was no longer present, he was introduced to his “back-to-Africa” ideas.

TO BRITAIN AND BACK TO GOLD COAST

After World War II Nkrumah headed to London where he met many “comrade-in-arms” from other colonies in Africa and the Caribbean including Jomo Kenyatta (Kenya), Abubakar Tafewa Balewa (Nigeria), and George Padmore (Trinidad), and he realized that they were all fighting a common enemy–white domination and exploitation. He managed to successfully combine his studies with his political activities and finally earned a doctorate in Economics at the London School of Economics, while helping to organize the Fifth Pan African Congress in Manchester in 1945.

Nkrumah was better equipped to challenge colonialism when he returned to the Gold Coast around 1947. He became a major voice in the United Gold Coast Convention (UGCC), a political convention bent on exploring paths to independence. Other major players in the party were Obetsebi-Lamptey, Ako Adjei, Akuffo-Addo, J. B. Danquah and Ofori Atta. Their focus was to spearhead a transition from colonialism/Gold Coast to independence/Ghana. As Nkrumah pushed for an end of the British colonial rule, he was optimistic with the groundswell of support the independence of India had set in motion, signaling the gradual process of Britain’s waning power over its colonial empire. But he was also frustrated by the sluggishness of UGCC’s progress, and was in favor of mass protests and civil disobedience. For this, the six leaders of the UGCC were arrested and detained under the Emergency Regulation in 1948, a provision used by the colonizers to stifle nationalist resistance. Upon his release, Nkrumah was more defiant.

He formed another party, more in line with his ideas of provoking nationalist fervor among the masses, which he believed would accelerate the process towards achieving independence. The new party was called the Convention Peoples Party (CPP) and it advocated strikes, boycotts and mass civil disobedience to openly challenge British rule. To expand his power base and inform the people of his ideas, Nkrumah traveled around the countryside proclaiming that the Gold Coast needed “self-government now.” His message was well received and as his influence widened, he began demanding more from the British, for the people who were becoming more dissatisfied with British policies.

With the support of the people on his side, Nkrumah boldly brought together a “people’s assembly” to hammer out some proposals leaning towards self-government to present to the colonial administration. Their proposals were rejected and Nkrumah called for “positive action” including civil disobedience, massive work stoppage, non-cooperation, boycotts and strikes on a national scale. Nkrumah, along with many of his supporters, was arrested for sedition and sentenced to three years in prison. This led to international protests and more internal resistance. The colonial government was forced to hold some tepid semblance of general elections, which resulted in unintended consequences. Though in prison, Nkrumah and his party won the election by a landslide and he was released from prison. This move placed Nkrumah as a powerful force as he gathered more momentum for the country’s independent movement.

With CPP holding 34 of the 38 legislative seats, the British governor departed and Nkrumah became the leader of the government; independence seemed just a matter of time.

INDEPENDENCE AND IDEOLOGY

The country was not fully and officially recognized as an independent nation even though Nkrumah was named its prime minister. And as the leader of the new government, he had to master the art of government quickly–on the job training–in order to justify his rapid push for total independence from the British government. On March 6, 1957, the Gold Coast became the independent country of Ghana–the first British colony to do so–with Nkrumah as its first prime minister. Ghana’s path to independence served as an incentive and a road map for the rest of the African continent, and Nkrumah was hailed as “Osagyefo,” which means “the victorious one” in the Akan language. By the mid 1960s, over 30 African countries had followed Ghana’s leadership and had achieved independence for their countries.

Ghana’s economy was strong and Nkrumah’s steady, gradual push towards independence had contributed generously. It was a beacon of stability, and more successful than many other African countries with a vibrant tourism industry, high market prices for its cocoa and gold trade, and visions of long range public works to boast the country’s infrastructure. Of great concern was Ghana’s dependency on foreign manufactured goods (the basis of slavery), and Nkrumah worked tirelessly to stem that potential financial drain by creating Industrial Development Corporation to promote domestic industrialization.

In 1960, Ghana became a republic and Nkrumah, its president. Following a course of international neutrality and political cautiousness, he sought economic and technical aid from the U.S. and the Soviet Union. He visited New York to address the United Nations General Assembly. While there, he renewed old acquaintances and was welcomed by an enthusiastic audience that included Minister Malcolm X, Congressman Adam Clayton Powell, and Chuck Stone of the American Committee on Africa. (Africa was becoming an area of interest to Black Americans). At the UN, Nkrumah was very explicit in his remarks concerning the colonizers and the wretched conditions they created (and left) in Africa. He said in part, “….The flowing tide of African nationalism sweeps everything before it and constitutes a challenge to the colonial powers to make a just restitution for the years of injustice and crimes committed against our continent….. For years Africa has been the footstool of colonialism and imperialism, exploitation and degradation…. But Africa does not seek vengeance. Africa wants her freedom! It is a simple call, but it is also a signal lighting a red warning to those who would tend to ignore it.”

Ironically, some of the methods Nkrumah employed, especially his visions of economic self- sufficiency, were partly borrowed from the colonial era because he did not have the time or the luxury, to implement new strategies. When the price of cocoa–one of Ghana’s main export–fell on the world market, the country’s financial reserve dwindled putting a huge drain on other economic resources and public works projects. High unemployment, rampant food shortages and high food prices resulted. The economic woes worsened and Nkrumah responded to the crisis by raising taxes. His administration was also reportedly beset by corruption.

Despite internal problems, Nkrumah was convinced that the unification of Africa was the only means to achieve total political and economic freedom for the continent–true independence. To create a working agenda for his unification idea, he called a series of conferences including the Conference of Accra and the All African Peoples Conference, each one inching closer to his vision of the United States of Africa. Then came the founding of the Organization of African Unity (OAU) in 1963, but many of the African leaders did not favor immediate political unification of Africa. Against Nkrumah’s wishes, they remained a “toothless” organization with great potential, but individually weak, because they failed to marshal the unity necessary to accelerate meaningful progress after colonialism and imperialism.

GONE, BUT NOT FORGOTTEN

As Nkrumah’s popularity declined, he became more autocratic. In 1964, he reportedly declared himself president for life. Though he appeared to be at the peak of his power, in reality, his days in office were waning. While on a state visit to Vietnam in 1966, the government of Ghana was overthrown in a military coup. Nkrumah was never allowed to return to Ghana. He lived in exile in nearby Guinea as a guest of President Sekou Toure until failing health caused him to be taken to Bucharest, Romania for medical treatment where he died in 1972.

Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois who lived in Ghana, at the invitation of Nkrumah, until his death in1963, made the following statement describing Nkrumah: “There can be no doubt that Kwame Nkrumah is the Voice of Africa…..the fight between colonial empires for the loot of Africa and Asia tore the world apart, and lifted partially the veil over the submerged peoples of the world. There came a new stirring of old centers of culture and in Africa, Kwame Nkrumah came to the fore….a Black West African peasant of the Akan tribe.”