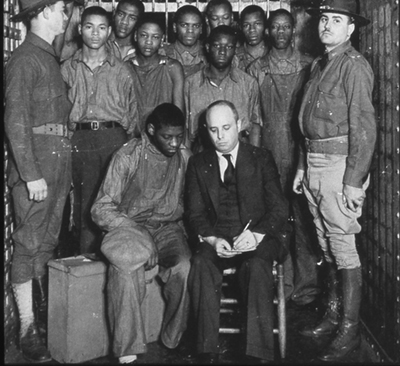

The Scottsboro Nine with their attorney

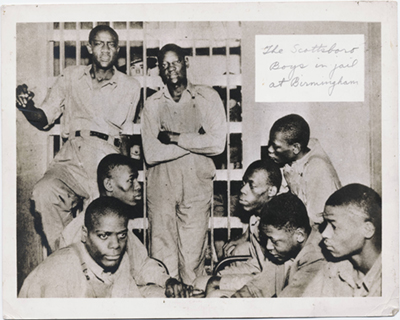

The Nine minus one in Birmingham Jail

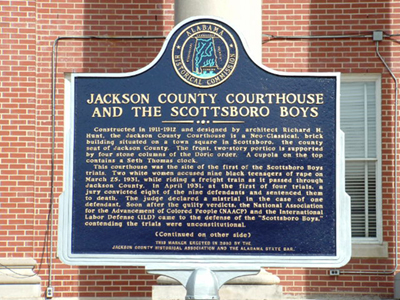

The Jackson County marker erected in their honor

*** Legends ***

By Yussuf J. Simmonds

The Scottsboro Boys

“They became the ‘poster boys’ of racism in the criminal justice system”

The names Olen Montgomery (17), Clarence Norris (19), Haywood Patterson (18), Ozie Powell (16), Willie Roberson (16), Charles Weems (16), Eugene Williams (13), and Andy (19) and Roy Wright (12)–brothers–are forever documented in the annals of the United States criminal justice system, and further highlighted the double standards–traces that are still found today. The time was 1931 at the height of the Great Depression and throughout the South–and also the North, East and West–riding the railroads (“hoboing”), looking for a better life, was a part of everyday life for large segments of general population, and particularly, the Black population. They were just looking for something … someplace …anyplace that was better that their status quo. They were called hobos then, but in today’s world they would be considered as part of the increasing homeless or vagrant population.

That was the setting specifically, the second year of the Great Depression (1929-1941): the stock market had just crashed, depressed world economies and high unemployment were the norm, and nine Black teenagers, all male–five from Georgia and four from Tennessee–left Chattanooga, Tennessee on a Southern Railroad freight train, heading west in search of government work in Memphis.

(Along the southern border of Tennessee, the state touches the entire northern borders of Alabama and Mississippi. Since Chattanooga and Memphis are situated near the southern border of Tennessee, it would be normal for a train traveling west from Chattanooga to Memphis to traverse in and out of the northern border of Alabama and Mississippi respectively).

While the nine Black teenagers were on the train heading west, they encountered several White teenagers who were also “hoboing.” A fight apparently broke out between them (the Black and the White teenagers), the latter jumped off the train in Alabama and reported to a sheriff that they had been “attacked by a group of Black boys,” who had also been riding the train. A call went out to “capture every negro who’d been on the train.”After locating and arresting the nine Black teenagers, they were initially charged for assault then charges of raping two White women (Ruby Bates and Victoria Price) were added–at that time, a normal occurrence against Black males particularly in the South, which dramatically increased the “lynch count” of Black males.

(A charge of raping a White woman by a Black man was a “capital” offense back then. Guilt and sentencing were often automatic and without appeal.

Thus began a precedent-setting era in the U.S. legal system that included a massive frame-up, a gross miscarriage of justice, via all-white juries, rushed trials, angry mob(s) and attempted lynching. These incidents would trigger decade-long looks at how the standard of justice differed for Blacks and would have a lasting impact on race relations and the justice system).

The case came to be known as the Scottsboro Boys, because it was first heard in Scottsboro, Alabama. According to the news reports, they were not allowed to consult an attorney before the trial, and most of them were illiterate. Eventually, there were three hastily-arranged trials, but the defendants received poor legal representation. After the Judge petitioned the Alabama bar for volunteers to assist the defendants, only one attorney volunteered, and he was a 69-year-old attorney who had not defended a case in decades–and was probably looking for his last “hurrah” to “go out” in a “flame of glory.” The judge then persuaded a Chattanooga real estate lawyer to assist him–a case of the blind leading the blind–who readily admitted that he did not have time to prepare–the case was on the fast track–and was not familiar with Alabama law, but agreed, anyway. Furthermore, neither attorney was not given time to conduct pre-trial investigations nor to research relevant case law. In addition, and some of the defendants were juveniles who were to be tried as adults.

(This was before Gideon v Wainwright (1963), the landmark U.S. Supreme Court case which the Court unanimously ruled that state courts are required under the Sixth Amendment of the Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases for defendants who are unable to afford their own attorneys.

Of course, the ruling never mandated “competent” counsel, or counsel that can handle the relevant case to which they have been assigned–since all lawyers are not “created” equal, they have varying specialties).

The defendants had to be escorted to the courthouse by over a hundred Alabama guardsmen, armed with machine guns. For the White citizens of Alabama, it was a day of fun and celebration in Scottsboro even though in its later ruling, the Supreme Court euphemistically described the situation as, “…the proceedings took place in an atmosphere of tense, hostile, and excited public sentiment.” When the verdicts of guilty were announced, the crowd inside the courtroom erupted in cheers, and so did the crowd outside.

The trial(s) proceeded at an extremely fast pace for its severity; there was standing-room only in the court room and the first trial lasted only one and a half days. In those days, the court reporting clerk used very “primitive” methods, and the race and charges against the defendants made any accuracy of reporting not very matter-of-factly. Of course, there were convenient exceptions. At the closing, the prosecution emphasized, “If you don’t give these men death sentences, the electric chair might as well be abolished,’ and that appeared to have been recorded accurately. And the “mild” defense made no closing argument at all.

In researching the trials, the atmosphere seemed to be that of a kangaroo court assisted by the Keystone cops. However, to the defendants not only were the court and the cops “kangaroo” and “Keystone” respectively, they were deadly. For while the jury was still deliberating the first trial, the second trial began. When the jury announced its verdict from the first trial, the jury from the second trial was taken out of the courtroom.

Eight of the nine Black defendants (Wright excepted) were convicted of rape and sentenced to death, the common sentence then in the South for Black men convicted of raping White women. The eight convicted ones were sentenced to death by electrocution in April 1931. The case was appealed and the state supreme court upheld seven of the eight convictions (Williams excepted).

Furthermore, the chief justice also ruled that the defendants did not receive a fair trial, fair sentencing, and had ineffective counsel. He further pointed out that as a result of ineffective counsel, the defense failed to make closing arguments which illustrated an example of under-zealous defense representation.

After the case was returned to the lower court, it was moved to another venue, which coincidentally was about 50 miles shy of the center of “ku klux klan-ville.” Again the defendants were tried and as expected, they were found guilty again, after three trials. Most notably, the court records show that there was an admittance of conflicting and fabricated testimony: one of the alleged victims asserted “none of the Scottsboro Boys ever touched either of us.” But the die was cast. The jury found them all guilty in two of the three trials. In the third trial, there was one Black juror, and though the jury again found them guilty, charges were finally dropped against some of the defendants. (At this time, which ones are uncertain).

The case of the Scottsboro Boys, as they had become known, dominated the headlines all over the nation; the defendants were defended by many in the North and attacked by many in the South. The case has been widely considered as a gross miscarriage of justice: the defendants were the only witnesses called by their attorneys in their defense. No new evidence came up. However, it led to the eventual end of all-white juries in the South.

Massive demonstrations in North especially in Harlem, the legal arm of the Communist Party, the International Labor Defense (ILD), to take up their cases. The next time the case was retried, the defense team argued that their clients did not have proper legal representation; no opportunity to assist in the preparation of their cases; had their juries intimidated by the large crowds of spectators; and that it was unconstitutional to exclude Blacks from the jury. The Alabama Supreme Court did not find any reversible legal errors.

The following year the same court ruled against seven of the eight remaining defendants, confirming the convictions and death sentences of all except 3-year-old Williams. The result: seven of eight rulings from the lower court were upheld. The court then granted Williams a new trial since he was a juvenile; that saved him from the threat of execution.

Eventually the case went to the U.S. Supreme in October 1932 and in a landmark decision the Court reversed the convictions stating that the defendants were denied due process which is guaranteed by the U.S. Constitution, regarding “effective” assistance of counsel at a criminal trial. In an opinion written by Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes, the Court found the defendants had been denied effective counsel.

However, the reversal ruling did not end the ordeal for the Scottsboro defendants, it only ruled that their due-process rights had been violated, not that they were not guilty. The case went back to the lower court for a retrial. Now a cause celebre, the case went to trial and the defendants were again found guilty and again it went to the U.S. Supreme Court and was sent back to the lower courts again for retrial.

When it was all over, the sentences ranged from 75 years to death. Seven of them served prison sentences; one was shot in prison by a guard. Two escaped, reoffended, and were sent back to prison. The oldest one, Norris,–and the only one sentenced to death, escaped and went into hiding in 1946. He was pardoned by the governor of Alabama in 1976. His autobiography, The Last of the Scottsboro Boys was published in 1979 and he died January 23, 1989.

Patterson escaped from prison in 1948 and published The Scottsboro Boy in 1950, before being caught by the FBI. He died of cancer in prison in 1952, after serving only one year of his sentence for another crime.

In July 1937, the state of Alabama dropped all charges against Willie Roberson, Olen Montgomery, Eugene Williams, and Roy Wright. The four had spent over 6 years in prison, the adults on death row.

The case has inspired and has been examined in literature, music, theatre, film and television. The movie, To Kill a Mockingbird, was loosely based on the Scottsboro case; in addition, there was a television movie titled Judge Horton and the Scottsboro Boys; a television documentary on the Scottsboro trials for its Greatest Trials of All Time series; and a documentary Scottsboro: An American Tragedy, which received an Oscar nomination.