Judge A. Leon Higginbotham

Higginbotham’s literary masterpiece

By Yussuf J. Simmonds

A. Leon Higginbotham

“A Militant Jurist (Judge)”

Some legal historians have described Judge A. Leon Higginbotham as one of the more prominent figures in American history; had he not been a judge, they say, he may have been a militant. Higginbotham was known primarily as one of the earliest Black federal judges and a sterling advocate for civil rights. For example, in a case called Pennsylvania v. Local Union 542, Int’l Union of Operating Eng’rs, he displayed the highest qualities of judicial integrity in an employment discrimination action when the defense requested that he recused himself. The opinion he wrote in response is a magisterial examination of the double-standards of racism: the false belief that Black judges ruled inherently in favor of Blacks; while White judges somehow were endowed with a sense of racial neutrality towards all parties.

It was a flat declaration that, in a world where White supremacy was supposed to be no longer tolerated, White litigants sometimes were going to have to deal with arguing before Black judges.

In From the Black Bar: Voices for Equal Justice: “An important stratagem used by Whites to deny meaningful political power to Blacks is their concerted effort to keep Blacks off the bench – and away from the bar, for that matter. On the bench, Blacks have varied opportunities the quality of justice for all people by improving it for their own people. Many of them seize those opportunities, not in a prejudicial but in a fair manner.

Theirs is no simple task because Whites never fail to set double standards of conduct – one kind for their own and another more difficult and disrespectful for Blacks. The idea is to use anything to reduce or eliminate the likelihood that Blacks will disrupt the social, economic and political order by pursuing equal justice …”

The attorney for Local 542, International Union of Operating Engineers, asked Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. to disqualify himself in a case in which the union was accused of racial discrimination. The request followed the judge’s address at the annual meeting of the Association for the Study of Afro-American Life and History in Philadelphia where Higginbotham sat on the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Pennsylvania. There he gave an address entitled, “Double Standards for Black Judges”: Being Black and the Appearance of Impartiality.

In his ruling, Judge Higginbotham demonstrated that true justice was indeed blind relative to those who appear before the bar of justice and he refused to recuse himself. (In legal terminology, recuse means to disqualify or remove oneself as a judge over a particular proceeding because of one’s conflict of interest. Recusal, or the judge’s act of disqualifying himself or herself from presiding over a proceeding, is based on the precept that judges are charged with a duty of impartiality in administering justice). In essence he was saying, that if White judges can be impartial in cases where the party or parties are Black, so too can Black judges when the party or parties are Black or White.

As a judicial officer, Judge Higginbotham has often been described as “a Man for All Seasons” or more correctly, “a Judge of All Seasons” because of the skillful and varied talents he displayed during his lifetime. He was a lawyer, politician, advisor to the President Lyndon B. Johnson, author, and judge. Not only did he serve in these various capacities, but in doing so he demonstrated an unusual devotion to intellectual honesty, fundamental fairness, and personal integrity throughout the course of his professional career. Whether as a lawyer, advocate, mediator, scholar, judge, mentor, advisor, expert witness, or teacher, Higginbotham personified academic excellence, unselfish compassion, and steadfast courage.

On a spring afternoon in 1950, as a first-year student at Yale Law School, A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. heard the promise of equal justice in the voice of Thurgood Marshall, then the chief counsel for the NAACP Legal Defense Fund, as Marshall argued before the United States Supreme Court in Sweatt v. Painter.

In 1946, Heman Marion Sweatt, an African American, was denied admission to the University of Texas School of Law. A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr. heard Thurgood Marshall plead for equal justice for Sweatt under the United States Constitution with outraged eloquence. And, when the United States Supreme Court held, in a unanimous opinion, that Sweatt had to be admitted to the “whites-only” law school, Leon Higginbotham was convinced that he had witnessed the birth of equal justice in United States Supreme Court.

Leon Higginbotham admired this NAACP Legal Defense Fund lawyer, this protege of Charles Hamilton Houston, this student of William Henry Hastie, who successfully challenged the separate but equal doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson and who “saved the soul of America” through Brown v. Board of Education. When the United States Supreme Court handed down its unanimous Brown decision on May 17, 1954, in the eyes of Leon Higginbotham, Thurgood Marshall became synonymous with the struggle for human rights.

To Leon Higginbotham, Thurgood Marshall, the lawyer, exemplified what lawyers can and should do for the betterment of their country. To Leon … and Maxcy …

IN MEMORY OF ANOTHER NOTED ATTORNEY MAXCY FILER, IN THE TRADITION OF MARSHALL AND HIGGINBOHAM, THE SENTINEL’S LEGENDS PRESENTS:

Aloysius Leon Higginbotham, Jr. was born in Trenton, New Jersey at a time when segregation in American society was the norm – the way things were. As a teenager in the forties, he suffered the indignities that Black people generally suffered and overcame tremendous obstacles to become one of the leading jurists in the country. But had it not been for an experience he endured as a teenager, there probably would not have been a Judge A. Leon Higginbotham, Jr.

In 1944, as one of the twelve Black civilian students at Purdue University, he was forced to live in a crowded barracks-style unheated attic while most of his white classmates lived in the campus dormitories. According to Higginbotham, one night as the temperature was close to zero, he felt that he could no longer suffer the personal indignities and denigration. He thought that it was ironic that the United States was fighting to “make the world safe for democracy” yet there was no room in that world for twelve Black students to be given a small corner of the heated dormitories for their quarters.

Higginbotham graduated from Antioch College in 1949 with a bachelor’s degree and then earned his law degree from Yale University in 1952. He started his legal career in the public sector as a law clerk in the Court of Common Pleas, and then as assistant district attorney both in Philadelphia. From 1954 to 1962, he was in private practice.

When Martin Luther King Jr. was killed, President Lyndon Johnson summoned him to the White House for his counsel in dealing with the national unrest that followed.

He left the private practice to be deputy state attorney general of Pennsylvania, then to the Federal Trade Commission and finally to his first judgeship. In 1964, President Johnson appointed him as a federal judge. President Jimmy Carter next placed him on the U. S. Court of Appeals, which is considered a stepping-stone to the U. S. Supreme Court.

In one of his cases, Commonwealth of Pennsylvania v Local Union, where Higginbotham was the judge hearing a case that involved Blacks, he was asked by one of his White colleagues to recuse himself since, according to the White judges, it would be difficult for him to be impartial. He refused and responded by saying that when there are cases involving Whites, do the White judges recuse themselves.

In 1979, he was a guest presenter at the annual Pioneer Awards dinner of the Brotherhood Crusade in Los Angeles. He presented the awards to an elite group of judges and attorneys, who were being honored for their legal accomplishments by the Brotherhood Crusade. The lineup included Johnnie Cochran, Jr., Leo Branton, Charles Lloyd, Judge Vaino Spencer, Judge Earl Broady, Sr., just to name a few.

After Clarence Thomas became an Associate Justice of the U. S. Supreme Court, Judge Higginbotham wrote him a public letter denouncing some of this decisions that sought to turn the clock back on the progress Blacks had made and from which he (Thomas) had benefited. This letter became as noteworthy as the one Dr. King had written from the Birmingham jail in the fifties.

Higginbotham retired from the bench in 1993 where he had become Chief Judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals and had attained the prestigious status of “senior judge.” He then became a professor of law at Harvard University.

As President, Bill Clinton awarded him the Presidential Medal of Freedom in 1995. In 1996, the NAACP awarded him its highest honor, the Spingarn Medal.

Higginbotham received the first Spirit of Raoul Wallenberg Humanitarian Award in 1994 from the American Swedish Historical Museum on the basis of his advocacy on behalf of America’s children within the legal profession and his human rights efforts in South Africa. The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law named its annual A. Leon Higginbotham Corporate Leadership Award after Judge Higgenbotham. Higginbotham was awarded honorary degrees from 62 different universities.

Higginbotham died on December 14, 1998 in Boston, Massachusetts, after suffering from a series of strokes. Former President Clinton described him as “…one of our nation’s most passionate and steadfast advocates for civil rights. I shall never forget how he spoke up for me.” (during his impeachment hearings). Rev. Jesse Jackson said of Higginbotham, “…what Thurgood Marshall and Charles Hamilton Houston were to the first half of this century, Judge Higginbotham was to the second half.” Former Congressman Kweisi Mfume said “…the world has lost one of its finest, most pre-eminent jurists of our times. His work is a reflection of both his deep passion for civil rights and his legendary pursuit of justice and equality for all Americans.”

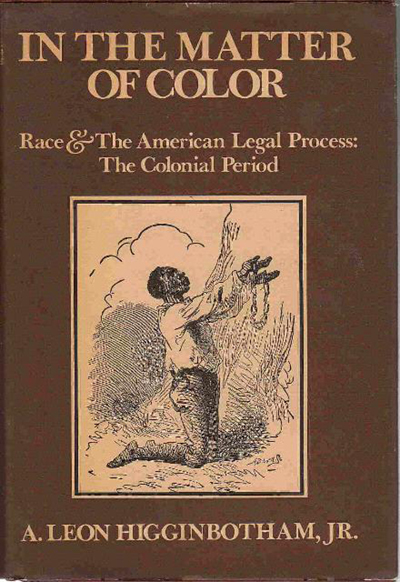

He wrote several books, one which received national and international acclaim, “In the Matter of Color: Race and the American Legal Process. About the book, Alex Haley commented, “Millions among those who read or saw Roots have expressed how shocked they were by the cruelties which inherently accompanied chattel slavery. But few realize to what degree the legal process of that era both sanctioned and perpetuated slavery’s myriad horrors.”

Judge Higginbotham was married to Dr. Evelyn Brooks and had four children: Stephen, Karen, Kenneth and Nia.