Harriet Tubman

The “Underground Railroad”

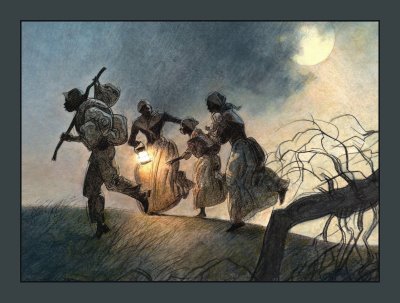

Slaves on the run

LEGENDS

By Yussuf J. Simmonds

HARRIET TUBMAN

“Called the Black Moses, she moved slaves through the Underground Railroad”

I’ll meet you in the morning

Safe in the Promised Land

On the other side of Jordan

Bound for the Promised Land.

Those words are a part of the Spiritual Code Harriet Tubman sung that were heard by waiting ears hidden in the slave quarters or standing deep in the woods signaling “Moses is here.” Though small in stature, Tubman was described as being strong as a man, brave as a lion and cunning as a fox; she made numerous journeys into the Deep South and led over hundreds of slaves to freedom. What triggered Tubman to become the conductor of the legendary Underground Railroad may have been the inspiration of her own experiences as a slave. When she was 15, Tubman had an experience that lasted her a lifetime. Trying to help a runaway slave, she encountered the wrath of the overseer of the plantation who hit her in the head with a lead weight. It put Tubman in a coma that took months for her to recover. The effects plagued her for the rest of her life.

The Underground Railroad was an informal network of secret trails, pathways, tunnels, safe-houses and routes that slaves in the United States used during the 19th century to escape to Free states and/or the Canada. The latter became the preferred destination since it was outside of the United States. Despite its name, it was neither “underground” nor a “railroad,” but the descriptive name given to the movement due its surreptitious undertaking. Those escape routes operated for many years before, during and after the Civil War. It was also called “Freedom Trail” and the name Harriet Tubman became historically associated with it.

She was born into slavery, the 11th child of Benjamin Ross and Harriet Green, in Bucktown on the Eastern Shore of the state of Maryland. Her parents had been brought from West Africa during the first half of the 18th century, having been taken from the Ashanti Tribe. After Tubman escaped from her slave-master, she first went to Philadelphia, where she worked tireless not to return to bondage. She described the feeling of her first taste of freedom: “I was free and I couldn’t believe it. There was such a glory all around and the sun was shining through the trees and on the hills. I was free!”

During her formative years, she was called Araminta–“Minty” for short. Tubman lived on a plantation that produced lumber and slaves, the latter to work, rent and sell. By the age of five, Tubman had been rented out, working fulltime cleaning White people’s homes and tending to their babies. She was adamantly opposed to working outdoors however, when she reached her teenage years, she was rented out again, but “this time” outdoors as a field hand. Her life on the plantation became unbearable and though she was a hard worker, she had a defiant and rebellious nature. Tubman’s dream of escaping gathered a fury within her against the system of slavery.

As an adult, she took the name “Harriet” for herself and around 25, she met a free Black man named John Tubman, and after getting permission from her master–which was necessary in those days–she married him in 1844; thus, Araminta “Minty” Ross became Harriet Tubman. However, she was still required to work for the master. In a strange twist of irony, according to historical documents, Tubman’s husband, though a free man, was not supportive of his wife’s yearning to be free.

It may have been that in order for Tubman to be a free woman, they would have had to leave Maryland, a slave state, and her husband, already a free man, was not willing to leave the state, and risk being tagged a slave. (In many states, Blacks were considered slaves, unless and until, they can prove otherwise, and often times, it was difficult and sometimes impossible. “Black-equal-slave” was the norm; “Black-equal-free-man” was the exception).

In 1849, after her master died, Tubman escaped; with sheer will and determination, hiding by day and walking by night, she fixed on the North Star and eventually reached Pennsylvania. Tubman had crossed the line for which she had been dreaming her whole life, the line into freedom. Even though she was “now” free, she was lonely without her family. There, and in other northern cities, she worked as a domestic for about two years, saving money to finance the rescue of her family. Then she returned to Maryland and spirited, first her sister and two children.

That started her mission which became known as the Underground Railroad.

Guided by the cover of darkness at night and extreme secrecy, Tubman brought her entire family and hundreds of other slaves to freedom, never losing a single one. In her own words, “… I nebber run my train off de track and I nebber los’ a passenger.’ However, sometimes there were those who hesitated or had a change of heart after having started on the ‘freedom train.’ In those instances, Tubman would level her pistol at the individual(s) saying, “You go on or you die.” Rewards began to surface for the recapture of the slaves–who had become fugitives–that Tubman was ferreting out of the slave states in the South. To her good fortune, she was never associated or named as the leader of the fugitives. Slowly, one group at a time, she brought relatives with her out of the state, and eventually guided dozens of other slaves to freedom.

When the Fugitive Slave Law of 1850 was passed, Tubman guided the escaped slaves farther north into Canada, and helped newly freed slaves find work. One of her strategies was that she always started the journey on a Saturday night. Tubman knew that even most businesses–the slave business and others–ceased on Sunday for church and it was impossible to advertise escapes or runaways, so that gave her a 24-hour head-start on any potential pursuers. During one of her trips, she went to get her husband but learned that he had been remarried since she had left the state.

To Tubman, skillfulness and guile became second-natured. She would often use a slave-master’s carriage to escape, covering her quarry with fruits, vegetables or baggage, and traveling all night on Saturday and Sunday before abandoning the carriage. Tubman’s logic was two-fold: first, it carried her “passengers” far and fast as quickly as possible; and secondly, if she was ever stopped and challenged, barring any unforeseen circumstance, White men would naturally assume that any slave boldly driving a carriage was on an errand for her master. And she was right.

Her most glorious moment was in 1857 when she brought her aged parents to freedom and settled them in Auburn, New York. By then, Tubman’s name and exploits were well known and she had earned a well-deserved reputation especially among the anti-slavery workers; she became a heroine of their crusade. They assisted her to raise funds which she used to purchase a home from then governor of New York, William H. Seward.

Tubman’s last underground expedition was in December 1860. The following year the American Civil War began. Tubman worked for the Union Army, as a cook, a nurse, an armed scout and a spy. Her knowledge of the country–learned during the time she operated the Underground Railroad–became invaluable to the Union. As the first woman to lead an armed expedition in the war, Tubman guided a raid on the Combahee River, which liberated more than seven hundred slaves. Many of the freed slaves, feeling obligated to the Union, eventually fought along with the Union, though in separate all-Black units. So added to her other talents, Tubman accidentally, and through necessity, also became a recruiter for the Union Army.

Later on, she would help John Brown–whom she believed to be the greatest American–recruit men for his raid on Harpers Ferry. They seemed to have much in common: they both loathe abolitionist and anti-slavery advocates who they claimed fought only with their voices (made speeches) and their pens. Evidence indicated that she was supposed to take part in Brown’s attack on Harpers Ferry, but she became ill and missed the raid. She held Brown in very high esteem.

After the war, Tubman returned to the family home in Auburn, New York, where she cared for her aging parents. She then began fighting other wars: to help freed Black men who had served in the Union Army; those who were freed and had no skills; and the women’s suffrage movement. She remarried to a Union Army veteran, Nelson Davis, who was in poor health and died shortly after. During the suffrage meetings, Tubman would re-tell her stories of exploits to help inspire and invigorate the women.

Eventually, she became ill and had to be placed in a home for the elderly … a home she had helped to open years earlier to care for elderly Black soldiers. Stories of Tubman’s journeys became legendary and her exploits were compared to the biblical story of Moses freeing the Israelites from slavery in Egypt. Hence, the name “Moses” was attached to her work.

TUBMAN’S LEGACY

Though there has always been a discrepancy as to the exact date of her birth; some sources said 1820/21 and others said 1823/25. Her death certificate listed 1815 to 1913; and her gravestone listed 1820 to 1913. The final consensus was that that apparently, she herself may not have known. Tubman was buried with military honors in Auburn, New York where a plaque in her honor also adorns the courthouse.

A statue of Tubman is in Tangipahoa African American Heritage Museum, Hammond, Louisiana; her home has been preserved as a museum and an education center. Several versions and biographies of her life have been written for children, including Harriet Tubman: Negro Soldier and Abolitionist. Many schools have been named in her honor; the U.S. Maritime Commission named its first Liberty ship, the SS Harriet Tubman, the first for a Black woman; and a U.S. postage stamp has been issued in her honor. Scholar Molefi Kete Asante has named Harriet Tubman, one of the 100 greatest African Americans.

Â