|

|

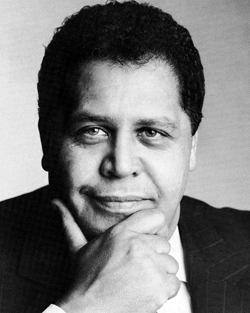

| Maynard Jackson |

When Maynard Jackson was elected the first Black mayor of Atlanta, Georgia, he also became the first Black mayor of a major southern city. (That same year Thomas “Tom” Bradley and Coleman Young became the first Black mayors of Los Angeles and Detroit, respectively). Atlanta was known as the “Gateway to the South” and Jackson maintained all the mystique that went with that title while he was the mayor. He served three non-consecutive terms. The city eventually renamed its airport the Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport in his honor. What he did to deserve that honor is the story of a true legend in the annals of Black history.

The great grandson of slaves, Maynard Holbrook Jackson, Jr. was born on March 23, 1938 in Dallas, Texas, to Jackson, Sr., a Baptist minister and Irene Dobbs Jackson, a professor of French, who taught at Spelman College. Young Jackson was seven years old when his father took over as pastor of Friendship Baptist Church, moving the family to Atlanta. His grandfather, John Wesley Dobbs, was very involved in voting rights issues and founded the Georgia Voters League. When Jackson’s father died in 1953, Dobbs became his surrogate father giving him his first taste of politics.

Through a special early-entry program for the gifted, Jackson enrolled in Morehouse College and became one of its youngest graduates at eighteen when, in 1956, he received his bachelor’s degree in History and Political Science. He then tried Boston University Law School, but was unsuccessful reportedly because of his youth and dropped out. After working at several entry level jobs in the New England area, Jackson decided to enroll in North Carolina Central University School of Law. Apparently, he had a calling to be a lawyer and in 1964, he graduated magna cum laude from Central University earning his law degree.

Back in Atlanta, Jackson worked as an attorney for the National Labor Relations Board and the year following his graduation, he married Burnella Hayes Burke. He made his first run at elected office in 1968 trying for the U.S. Senate and even though he was not successful, he gained tremendous public attention. The following year, he became the vice mayor of Atlanta, a largely ceremonial position that is also the presiding officer of the board of aldermen.

Taking advantage of Atlanta’s changing demographics, Jackson challenged the Mayor forcing him into a runoff in which Jackson was successful causing a shift in the city’s political structure. He was inaugurated in January 1974. Since the city had become almost 50 percent Black, he aggressively implemented an affirmative action program guaranteeing a level of prosperity—while simultaneously increasing Black migration and participation—and a sharing of municipal contracts in proportion with the population statistics. Atlanta became a Mecca for aspiring Blacks from across the country. Needless to say, he made political enemies in high places.

However, his personal life suffered despite his political success. The Jacksons had three children: Elizabeth, Brooke and Maynard III before divorcing in 1976. (His first child was born the day Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was buried). In 1977, at the end of his first term, Jackson remarried to Valerie Richardson and fathered two more children: Valerie and Alexandra. His terms as mayor saw extensive growth efforts for the citizens of Atlanta that “Fortune” magazine rated the city as “Best American City” for business.

During this period Jackson guided the building of a brand new airport, the largest and the busiest at that time—the Hartsfield International Airport. It was completed ahead of schedule and under the proposed budget. This feat propelled Jackson’s administration as a role model of fiscal municipal responsibility and visionary leadership. Because of term limits, Jackson was only able to serve two four-year terms as mayor, but during those eight years Atlanta reportedly had unprecedented economic growth, newly-found internationalism (mostly because the new airport facilitated international air carriers), public-private partnerships and racial harmony.

As a part of his tenure as the city’s chief executive, he worked diligently at reforming the police department which helped maintained racial harmony throughout the city. Jackson had campaigned against police brutality and for equity in hiring practices. However, there was a major sore spot in an otherwise smooth period of police-community relations. Jackson had to use all his skills to keep the peace and maintain calmness when Atlanta was rocked by string of brutal murders of young Black boys. After an intense effort of a combination of federal and local law enforcement working together, the murders was solved and the perpetrator convicted and sent to prison. The stench of that episode hung over the city for a few years after the case was solved. Rising homelessness also seemed to put a damper on many of Jackson’s other achievements.

When he returned to the private sector, Jackson resumed his legal career as a municipal bond attorney as the managing partner of a law firm where he specialized in public finance law. His legal skills were in great demand since he was a member of the Bar in Georgia and New York. Also he remained close to local and regional politics playing a key role in Atlanta being chosen to host the 1996 Centennial Olympic Games. For that, Jackson was named attaché for the United States of America in the Centennial Olympics.

After eight years as a private citizen, Jackson decided to run again for the mayor’s office—his third term. He won with 79 percent of the vote. Another one of the milestones as mayor was the installation of MARTA, Atlanta’s rapid transport service, a boon to public transport. Jackson worked to modify the city charter changing aldermen to city council members and the vice mayor to president of the city council. Health considerations and scandals relating to the airport reportedly became factors near the end of his third term and Jackson declined seeking a fourth term. During his third term, he had also undergone by-pass surgery for arterial blockages. Eventually he returned to the bond business founding Jackson Securities.

As chairman of his own municipal underwriting firm, Jackson participated in bond measures in some of the nation’s largest municipalities including Chicago, Memphis, Los Angeles, New York, Oakland and Philadelphia. The firm earned a reputation of superior integrity, sound business practices and impeccable performances in public finance. Jackson made millions while delivering a quality product ensuring measurable results.

Jackson never strayed too far from the center of the political activities—local and national. Active in the Democratic Party, he unsuccessfully sought the Democratic National Committee chairman but settled for the party’s national development chairmanship. In 2002, he founded the American Voters League in an effort to increase national voter registration.

In person, Jackson was described as a large-than-life figure; he stood over six feet and weighed about 300 pounds. On entering a room, he demanded “presence” combined with a soaring oratorical ability and a deep, booming voice. With his massive size came massive health problems; he reportedly suffered from diabetes due to his obesity and possibly high blood pressure. On one of his out-of-town trips, Jackson suffered a heart attack at the Reagan National Airport outside Washington D.C. He was transported to nearby hospital in Arlington, Virginia, where he died shortly after.

Due to the unexpected nature of his death, his wife, Valerie R. Jackson carried on the work at Jackson Securities with the same passion as her husband eventually becoming an advisor.

“Legends” is the brainchild of Danny J. Bakewell Sr., executive publisher of the Los Angeles Sentinel. Every week it will highlight the accomplishments of African Americans and Africans.