Most of the women in Samuel Little’s hand-drawn portraits seem to be frowning.

Their hair is short and curly or long and straight. They stare straight ahead or slightly off to the side. Some wear lipstick and jewelry.

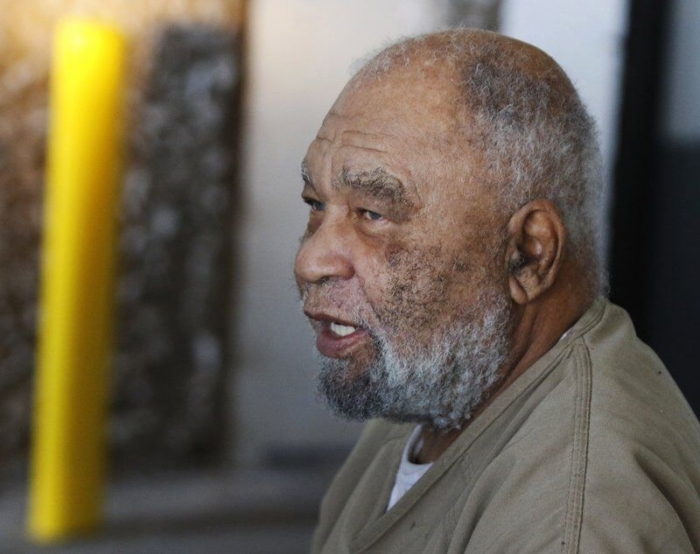

Little, whom the FBI identified this month as the most prolific serial killer in U.S. history, produced startlingly detailed likenesses of dozens of women he says he strangled over the course of more than three decades. Now the FBI is publicizing his portraits— hoping that someone, somewhere, will recognize the face of a long-lost loved one in an image drawn by the killer himself.

“I’m not sure I have a better solution in terms of how to get the information out there and how to notify families,” said Claire Ponder Selib, interim executive director of the National Organization for Victim Assistance. “But I can only imagine seeing a drawing by the killer of your mother or your sister or your daughter who may have died 20, 30 years ago. … Honestly, I struggle with this.”

The FBI’s publication of the images was made possible by a unique set of circumstances: The killer was not only willing to confess his crimes but had a vivid memory of what his victims looked like and sufficient artistic ability to reproduce their faces. A Texas ranger who interviewed Little noticed he liked to draw and gave him art supplies behind bars.

The 79-year-old California inmate went on to produce more than 30 color portraits, which the FBI hopes will help law enforcement match Little’s confessions to victims who, in many cases, have yet to be identified.

“The tactic of having a serial killer draw composites of his own victims is unprecedented,” said Enzo Yaksic, a crime researcher who helped build the first national serial killer database. “This goes to show how serial killers retain minute details of their crimes and mull them over years later as these are the conquests that made them feel powerful and in control.”

Little, he added, could “inflict trauma on his victim’s relatives indirectly with the drawings and that is undoubtedly a small payoff for him.”

Little has confessed to 93 slayings across the nation between 1970 and 2005, targeting prostitutes, women addicted to drugs and others he thought wouldn’t be missed. Law enforcement agencies in several states have been able to confirm 50 slayings. They are working to verify others, but have been stymied because, in many cases, there is no missing person report and no body.

An FBI crime analyst who has been working on the Little case for more than a year said investigators felt they had little choice but to publicly release the portraits.

“At this point all we have left is to appeal to the public to help us resolve these cases,” said Christina Palazzolo, an analyst with the bureau’s Violent Criminal Apprehension Program. “It was just in an effort to try to get as many eyes as possible on the unmatched confession details.”

Palazzolo added that investigators didn’t want to “retraumatize” anyone who lost a loved one.

“We’re sensitive and don’t want to upset anybody. We are just trying to bring some measure of closure and justice,” she told The Associated Press.

The heavy publicity surrounding Little’s case has yielded fresh leads from people who lost relatives or friends years ago, Palazzolo added.

Little’s portraits recently allowed police in Akron, Ohio, to provide answers to the family of Roberta Tandarich, whose decomposing body was found in a wooded area nearly 30 years ago. Authorities had long ago ruled the cause of death as “unknown/undetermined,” but her family suspected she had been murdered.

The Akron Beacon-Journal reported Friday that a detective summoned Tandarich’s daughter, Tonya Maslar, to the police station and showed her a portrait of a woman drawn by Little. The image was labeled “Akron, left in woods, 1990-91.”

“That’s her!” Maslar said. The paper said she cried and hugged her husband.

Attorneys for Little have said he is in failing health, and investigators are conscious they could be running out of time. In some cases, investigators will want to interview Little about cases to get more details from him.

Even after his death, law enforcement will be able to use his DNA and detailed videotaped interviews to close cases, Palazzolo said.

As for the portraits, Eric Witzig, a former homicide detective and FBI analyst, said it was “brilliant investigative technique” to have Little draw his victims.

“There will probably be some shock and trauma to the family,” said Witzig, who, along with Yaksic, helps lead the Murder Accountability Project, a group that tracks unsolved homicides. “You have to balance that against the interests of justice in terms of closing a homicide and fixing responsibility to the perpetrator.”