On Sunday, September 24, The Mark Taper Forum presented the opening night of the Public Theater and Berkeley Repertory Theatre’s production of “Head of Passes,” headlining multi-award-winning (television and stage) actress, Phylicia Rashad, accompanied by a cast of adroit supporting actors with prestigious careers to boot. Written by Tarell Alvin McCraney and directed by Tina Landau, the show’s program denotes the setting as “a house near to the Head of Passes, where the Mississippi River meets the Gulf of Mexico.” Without Google Maps, I’m figuring like the one of those Southern Bayou towns where gumbo rules. The time period: “A Distant Present.” Rashad portrays Shelah, the matriarch, strength, and backbone of a Black family connected by love, dysfunction, and either really bad luck or bad karma. Yes, there is love here but underneath it all, the hidden family secrets of abuse, metaphorically well-up, seep into and flood the house, as if to purify it from a past sin.

The supporting cast; Alana Arenas (Cookie), John Earl Jelks (Creaker), Kyle Beltran (Crier), Francois Battiste (Aubrey), Jacqueline Williams (Mae), and J. Bernard Calloway (Spencer), are in deep waters, dealing with Shelah’s flooded living room in the midst of a passing storm. They establish a family dynamic that is believable and likable; they care about Miss Shelah and the comedic jousting diverts us from some of her hellish moments. And there are grievous moments; the kind of scenarios we never want to see or experience. She is hiding the devastating news from the family but Dr. Anderson (James Carpenter -) begs her to share the truth about her failing health. Does Dr. Anderson see symbolism in the storm and flooding? Sheila does have her life-long confidante, Mae, that friend who has known the kids since birth, the auntie who isn’t the blood but, she – family. We need Mae to keep the peace with subtle comedic jabs and frank realism.

We don’t know what the medical issue is, but Shelah doesn’t have a lot of time left. She is determined to make an egregious wrong, right, hopefully absolving her of the denial and betrayal that affected an innocent child’s life for the worse. We want to believe this tumult can all work out but McCraney slips in those scenarios that take this family one step forward but three steps back. Creaker and Spencer remind of those middle-aged uncles with no business trying to fix leaking roofs. But they, along with a coming-to-age Crier, slosh through flooded rooms like bickering kinfolk, not knowing that, what seems like a natural disaster, is a long-time coming curse.

Cookie, Shelah’s half daughter, visits for her birthday, She is pregnant again with her third child. She’s that ’round the way girl who likes her Swishers blunts, hot chips, grape soda, and hardcore bruhs from the streets. The role of a thug is to protect his girl at all cost … trust. Arena’s helps us view the Cookies of the world from a different perspective; perhaps, they too have an unfair secret past that has stolen a part of their youth and soul. From a distance, like most drug addicts, Cookie is that familiar member of the family who made poor decisions. They love but her but when Cookie comes over, Mae knows better than to be caught slippin’. But other than Shelah, the family is unaware of Cookie’s childhood horror – the dark secret Shelah turned a blind eye to when her husband was alive and the Cookie was a defenseless innocent child.

Whatever this menace did, Shelah wants to make right by it, offering Cookie part of the house and refuge from the streets. But cookie wants nothing to do with a house that reminds her of such suffocating betrayal and helplessness. She just wants the dope money and we understand why, now. So, when she steals Shelah’s jewelry and jets out, Shelah understands. But Aubrey – who told the family to keep an eye on that girl – doesn’t understand because we don’t always know our people’s truth; that unknown abuses break the spirit of the young, whose fodder is replaced by drugs and other coping tools of diversion to help forget. But now, all Aubrey can do is hope he catches Cookie before she makes it to the pawn shop (and they always have a ride set up).

Perhaps, the monotony in this production is simply fate. Sometimes, the best tragedies provide just as much hope and optimism, just before taking it all away from us. This work reminds us that, at some point, you have to deal with life and death, up close and personally with your God. And when that conversation happens in “Head of Passes”, Rashad talks to God from the depths of her anguish; she is Job in the form of a southern Black woman, who can’t figure out why God would put her through such anguish. “You will speak to me! You will speak to me now … Lord!”

When Shelah converses with God – in ankle-high waters – there is an element of characters, Vladimir and Estragon, from Samuel Becket’s Waiting For Godot. In both stories, the main characters are waiting for some kind savior and sign, but it never comes. In the process, Rashad’s bears the creative challenge of splitting Shelah’s conflicting voices; one of reason, optimism, and praise, the other, a frenetic beckoning for a miracle. This woman is lost; God is not answering her and she’s pissed off about it. McCraney commits to intense and lengthy dialogue that only a seasoned actor like Rashad can pull off. Landaund gives Rashad the freedom to experiment with literally dying, night after night, on a Downtown L.A. stage. Even with Rashad conjuring the plethora of emotions such a soliloquy demands, at times, the dialogue lost its punch. But, if we were in Shelah’s mess, and God didn’t answer, we’d keep on rambling too.

If things couldn’t get any worse, Crier, Mae, and Creaker have bad news … there’s been a murder, and Aubrey and Cookie are dead. The way panicked Crier explains it, Aubrey died by that pre-mentioned street code. But Cookie … damn, she had a chance but this curse is real! It can’t all be true but somehow it is. This is that moment when life literally comes crashing down, to a point where your only option to face your reality and make an atonement for your mistakes. Shelah doesn’t know whether to curse God or scream His name in praise, begging for signs that aren’t there. “I need to see it now … Now Lord!!! I need!”

Rashad forces you to check yourself and your own mortality; she sacrifices physically to bring to life the real moments of a dying mother whose life is falling apart before our eyes. She goes to unsafe places physically, to make this character vulnerable, angry, submissive, humbled, and believable. The symbolism here, is, when the ills and injustices are bad enough, the return can decimate what took years to cultivate, and the estate collapses. Perhaps, this house was never a home. Rashad is still our mother from the ’80s, just a little older but still teaching and preparing us for life (and death) in “Head of Passes”. We root for Rashad because she represents all that is phenomenal, royal, consistent, and Black (unapologetically).

McCraney has written a tragedy that forces us to listen to a battered woman, who needs answers, and so do we. He spoke to the writer Julie McCormick, in her article, “Shining a Light on Tarell Alvin McCraney”… “The idea of opening up the dialogue about a person’s personal faith was and is always the main focus of the piece,“ he said.

See this play because life is too short not to appreciate the great work of the cast from the perspective of a rising young Black male playwright (a Yale grad at that). If your mama is still living, take her too. If not, you’ll want to call and check on her right after.

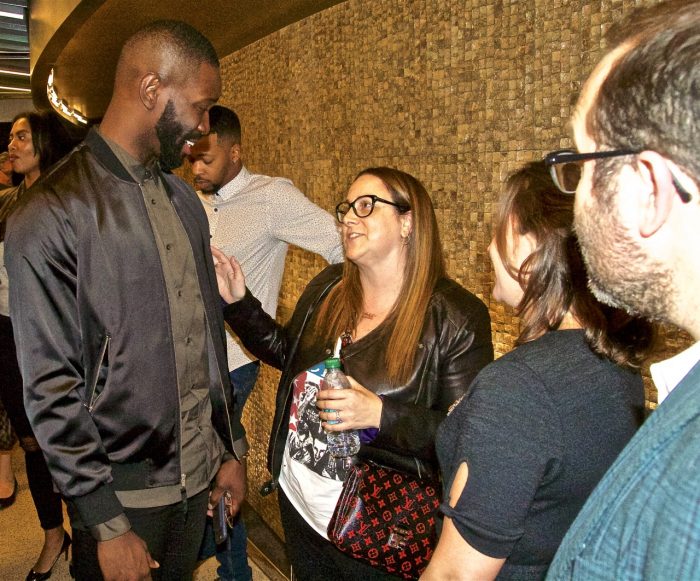

(L) Head of Passes” writer Tarell Alvin McCraney, is greeted by emotional well-wishers at the Opening performance. The production runs through October 22, 2017, as part of Center Theatre Group’s 50th anniversary season at the Mark Taper Forum. (Photo E. Mesiyah McGinnis / LA Sentinel)

The play runs through October 22, 2017. Scenic Design, G.W Mercier; Costume Design, Toni-Leslie James; Lighting Design, Jeff Croiter; Sound Design Rob Milburn and Michael Bodeen; Wig and Hair Design, Robert-Charles Vallance; Associate Artistic Director, Kelly Kirkpatrick; Production Stage Manager, David S. Franklin. For more info on the production visit the link http://marktaperforum.ticketoffices.com/Head+of+Passes

Additional post show photos by E. Mesiyah McGinnis / LA Sentinel