On March 3, 1991 the infamous Rodney King led LAPD on a high-speed chase through the city of LA. After King surrendered to the police, he was brutally beaten by officers Laurence Powell, Theodore Briseno and Timothy Wind for resisting arrest. While the officers were beating King, a nearby resident videotaped 89 seconds of the three officers beating King with their batons and kicking him long after he was incapable of resistance. Soon, the video was released to the press and a national outrage erupted around the world.

Twelve days later, Sergeant Stacey Koon and officers Powell, Briseno and Wind were charged with assault with a deadly weapon and excessive force. Since Koon was one of the commanding officers at the scene of the crime, he was charged with aiding and abetting. Both Powell and Sergeant Koon were charged with filing false reports.

Although the Black community’s relationship with law enforcement and the criminal justice system is known for being shaky, people expected all three officers to be found guilty.

However, on April 29, 1992, the all-white jury issued a not guilty verdict on all counts except for Powell’s assault charge. As a result, civil unrest broke out in the city. The media rushed to capture the historic imagery of the events that took place that day.

As the anniversary of the L.A. Uprising approaches, the L.A. Sentinel had the opportunity to sit down with one of the demonstrators involved in the L.A. Uprising, Mark Craig.

Craig is a Monrovia, CA resident, father and veteran. When the L.A. Uprising happened, he was a freshman in college. Outraged, he and a group of his friends left campus and went to downtown L.A. to protest.

“I went home and watched the verdict on television,” said Craig. “When they came back innocent, it just felt like a big slap in the face. A couple of my friends called me and said we need to go protest. They all met at my house and the four of us got in my little Datsun 280z and drove down the 110 freeway not knowing where we were going.”

While driving, Craig approached City Hall and drove pass 50 protesters outside Parker Center, formerly LAPD’s police headquarters. Craig and his friends joined in and as the night grew, more protesters came to voice their opinion. During the protest, the protesters were watching television to stay up-to-date on everything happening throughout the city.

After watching the national live broadcast attack of Reginald Denny, a construction truck driver who was almost beaten to death by a group of Black individuals known as the “L.A. Four,” a spark was ignited inside Craig and the other protesters at Parker Center and the chaos began.

“It just enraged everyone at Parker Center and took things to another level,” said Craig. “At that point, we started to gather around the police. There might have been 50 to 100 officers there but, there wasn’t enough of them for the amount of protesters that were there.”

The officers at Parker Center began retreating back to headquarters and grabbing weapons while rioters began rushing the building and breaking glass.

“The fear on their faces was if these people come in here, they were going to have to shoot. They were going to have to stand their ground,” said Craig. “From my perspective that night, if anything was going to burn that night, it was going to be Parker Center.”

While protesting, Craig explains that people were following his lead the entire night. But, he was concerned that some of the protesters could potentially die. Although he wasn’t afraid of dying that night, he tells the Sentinel, he didn’t sign other people up to die that night. He decided that he as well as the other protesters needed to stop.

“That’s the only time in life I ever felt, not afraid to die,” said Craig. “Even though I served in war, not even coming close to that feeling of okay this is worth fighting for. People were following me the entire night, whether it was me telling them to get around the police or do this or do that. That’s the night that I became a natural born leader. I was able to have all of these strangers that I never met in my life follow my directional foot, learn how to protest, and how to make the police go back inside the police headquarters.”

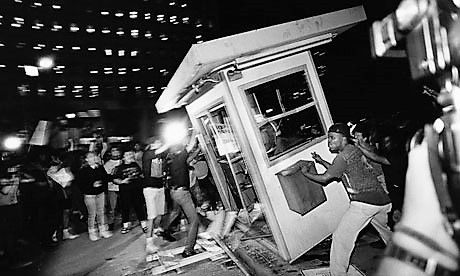

Craig, joined by a group of other protesters, made a barrier between the police officers, the glass and the protesters. After creating a barrier, he was able to get the protestors to stop breaking glass and instead focus their attention on a kiosk located in the parking lot at Parker Center.

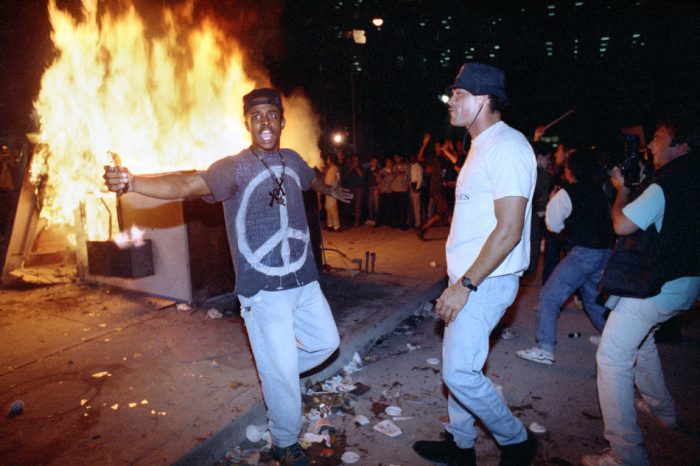

“The kiosk got tipped over and started to burn and that’s when my image was captured and became what CNN calls the iconic symbol of the Los Angeles Uprising,” said Craig.

When asked why these particular images are known to be some of the most iconic images of events that took place that night, Craig expresses that it might have been due to his level of energy that day or the irony behind him wearing a t-shirt and hat with a large peace symbol on the front while a fire burns behind him.

Craig’s image was used by numerous publications and television stations across the country.

25 years later, people are still discussing the L.A. Uprising and how the historical event changed the city. Craig believes this is one of the proudest moments of his life aside from the birth of his children.

Life after the LA Uprising

After the L.A. Uprising, Craig knew that it was important that he live a positive life and put out a positive image of an African American male.

“I was always going to live a positive life anyway, but I didn’t want society to be able to look back at that person who was called a looter and a hoodlum by then governor Pete Wilson and say, I told you so,” said Craig.

Today, Craig is not an active protester however he has retired after working 20 years in corporate. He has also spent time volunteering as a football coach for over 10 years and mentoring young Black men. Now, he has his own company called “MC Adventures,” where he gives tours locally around L.A. and Yosemite.

“That was my part in doing what I could do for the community,” said Craig. “I have always looked it as each of us need to work in our own community and make sure our own community is taken care of. If we did that, then that would just spread across the nation.”

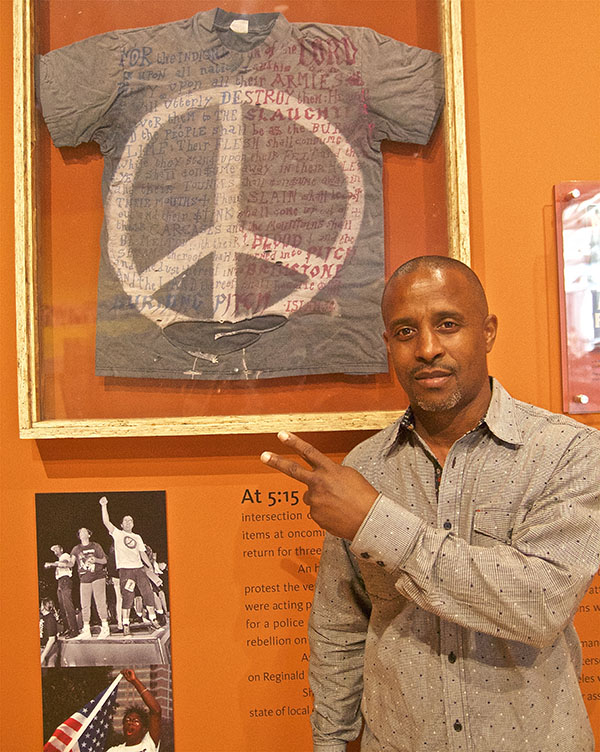

This past month, the California African American Museum (CAAM) asked Craig if he would be interested in participating in the six-month exhibit highlighting the African American immigration from the South, various historical rebellions, Latasha Harlins and the plight of African American scare in the city of Los Angeles. The exhibit ends with the L.A. Uprising.

“I donated several items that I still had from that night including my shirt, which is the big peace shirt that was on the cover of Newsweek Magazine,” said Craig. “I feel proud to walk into a museum and see yourself, people see me as a living legend, and it’s true. That’s the feeling that you have, you are a part of history. It is overwhelming to know that is going to be the legacy I leave behind for my kids.”

Recently, Craig wrote a book title, “Ain’t a Damn Thing Changed.”

“It was for myself to mainly document that night for me as a protester so that I can pass that on to my kids so they can know this is how I felt that night,” said Craig.

The book will be released this year and will be available for purchase on Amazon.

The primary thing Craig wants people to take away from the image, his book and the exhibit is for them to wake up.

“We have a lot of people who are sleeping and complacent,” said Craig. “This generation and it just continues to get worse and worse in my eyes. People aren’t really caring. Not just the young generation but my age generation as African Americans we need to wake up.”