Â

Who Will be the Next Police Chief?

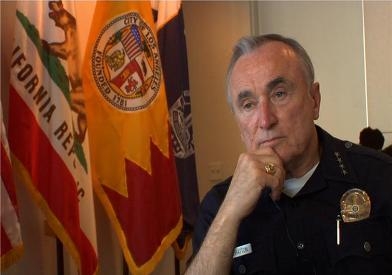

Chief William Bratton

Jasmyne Cannick

With LAPD Chief William Bratton stepping down on Saturday, he granted an exclusive interview with the Sentinel to discuss the Black community and who he would like to succeed him.

Â

Special to the Sentinel by Jasmyne A. Cannick

The relationship between Black Los Angeles and the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) is one that has been documented and immortalized in films, home videos, rap music, television news, and through the memories of those who have lived to tell about it-the good, the bad, and the ugly. African Americans have seen their fair share of police chiefs come and go. Some exits were cause for celebration and a sigh of relief like that of former police chiefs William H. Parker, Daryl F. Gates, and Willie L. Williams. Other exits were not as celebrated or approved of including the former Mayor James Hahn’s decision not retain then police chief, now 8th District Councilman Bernard C. Parks. But with each exit African Americans held their breath in anticipation of who would be next to fill L.A.’s top cop position-more importantly what would be the impact on a relationship between a notorious police department and its Black residents that at times was one video-captured beating or killing away from all hell breaking loose.

So when Hahn, who had lost the support of the Black community after his decision not to retain Chief Parks, announced that outsider William Joseph “Bill” Bratton, a white man, was to be appointed to the position of LAPD’s chief in 2002, African Americans by and large felt like it was going to be business as usual with the LAPD again. But with Chief Bratton, it was anything but.

Seven years later, L.A.’s top cop is leaving Los Angeles behind – officially stepping down Saturday – after being reappointed to a second five-year term, the first reappointment of an LAPD. chief in almost twenty years, and Councilman Herb Wesson’s proposed amendment to the City Charter that would have allowed for Bratton to serve a third consecutive term as police chief. Bratton made the big announcement back in August that he would be moving back to New York City to take a position with a private international security firm called “Altegrity,” serving as a CEO of a new division. There he will be a consultant on security for police departments worldwide. The Sentinel went one-on-one with Chief Bratton about his thoughts regarding race relations, today’s LAPD and the future of the department after he is gone.

“I chose Los Angeles because of the problems they were having with race relations,” Bratton said. “And quite clearly, the African American community was having major problems and had been having them for many generations with the LAPD. So the idea was to reach out, even before I got here, and also to be very responsive to what the concerns of the community were. It was ironic that they had a great anger and dislike for the department, yet they still wanted that department to be in their community trying to make the community safer. What they resented was how it was being done. The idea of being very aggressive, for many years, was seen as very demeaning, the way it was done, and it was as if it was being done to the community instead of being done for the community.”

Chief Bratton’s comments echo the feelings of many who felt that they had been the extracurricular activities of the LAPD for decades. From the 1962 controversial shooting of seven unarmed members of the Nation of Islam including the death of Ronald Stokes; then ten years later, Elmer “Geronimo” Pratt was framed by members the LAPD and FBI; the Rodney King beating; the O.J. Simpson trial; and the beating and asphyxiation of a Street gang member, that triggered the Rampart Division C.R.A.S.H. scandal which led to the federal consent regarding numerous civil rights violations-you could say that L.A. and its police department had its fair share of problems.

“You cannot argue with the fact that most crime occurs in minority and poor communities, that’s the reality,” Chief Bratton explained. “It’s done by minority and poor members of those communities to minority and poor members of those communities. Sometimes it would spill over to an adjacent community-white or Latino or vice-versa which in that case oftentimes would get much more publicity than just what is happening inside the community. And so my style of policing is to go where the problems are and that mean going into the inner city neighborhoods, Brown and Black, where most of the crime is committed and where most of the victims live but to do it in a way that was different from the way that it was done in the past. Do it constitutionally; we can’t break the law to do it. Do it compassionately. We’re dealing with human beings and while some of those human beings are contemptible in terms of their lack of respect for human life – the ability to kill and hurt, maim and rape – you’re still dealing with human beings, and so you still have to deal with them with a degree of respect. And lastly, you have to do it consistently. Consistently, meaning you don’t police differently in this community than you police in another community. You try to police fairly.

“And something that I’ve fought for from the beginning was that this was a city, because there were so few police, everybody wanted their police and they didn’t want to share them. I insisted right from the beginning, I was going to put a lot more police in those neighborhoods with more crime. And in the case of Los Angeles, that’s South Los Angeles, that’s Hollenbeck, it’s certain areas of Wilshire, certain neighborhoods in the valley, and that didn’t go well with a lot of political leaders and a lot of community groups; everybody wanted their share. But we had to put them where most of the crime occurred. I put 50 additional officers on Skid Row. It’s worked quite well.”

Earlier this year at a press conference, Chief Bratton remarked that L.A. was never going to get rid of gangs, a statement that didn’t resonate too well throughout the community. “I’m a realist, I also tell it like it is. I don’t sugar coat anything, that’s one of the things that people like about me. I am plain speaking,” he continued. “I remember about a week after I was sworn in as Chief of Police, there was a demonstration, and back in those days, there were a lot of demonstrations outside of police headquarters demonstrating against police brutality. There was a group of people out there with a bunch of signs that read ‘Bratton control your cops.’ And as I was going to a meeting I was walking through the crowd and they’re all lobbying and yelling and waving signs at me. I charged them and said control your kids. Basically, that’s what it’s all about: kids 15 to 25 that have parents that have somebody in their lives that’s supposed to be controlling them. We, the police shouldn’t have to be controlling somebody else’s kids but we are, because unfortunately a lot of people lost control of their kids. That didn’t set well with a lot of people. A lot of other people said that was something that needed to be said. And the idea was, don’t expect the police to be substitutes for moms and dads that are not there or who are there, and are not controlling their kids.

“There are always going to be gangs. It’s part of the culture unfortunately in the African American and in the Latino community. One of the things we know is that we can control the behavior of those gangs tremendously better than we did in the past. In 1990, there were 1100 murders in the city – over half of them were committed by gangs; that’s an average of 3 murders a day. Right now, this year, this month, we’re averaging a murder about every three days. We’ve had nine murders in 26 days. One every the three days in a city with 400 gangs, 40,000 gang members. So what we’re able to do is by policing smarter that we’ve been able to reduce the violence of those gangs. What is it that attracts our attention to those gangs; it’s their violence. It’s their influence on neighborhoods, where businesses don’t want to invest or where they kidnap your kids. There are almost a million school age kids in this city. How many of them are in gangs? About 15,000 out of one million, .015 percent. We tend to always look at the half full instead of the positive. The fact of the matter is that vast majority of the kids in this city will never go into a gang but they’re going to be influenced by the violence of the gangs. So what do we want to influence. We want to influence the violence of the gangs and we’ve don’t a very good job of that.”

A long time fan of suppression, prevention and intervention when it comes to getting a grip on gangs, Bratton has spearheaded groundbreaking intervention programs and partnerships with noted civil rights attorney, Connie Rice and her Advancement Project. He leaves behind the groundwork for the LAPD’s latest efforts at intervention and a re-entry program for felons that will provide job training and job placement assistance.

Responsible for covering 473 square miles and over 3.8 million residents, the LAPD, like the city it has sworn to protect and serve, has grown to just over 10,000 officers. The most visible change is the department’s composition: 40.7% of its officers being Latino, 38% white, 12% Black, 6.7% Asian and 2.6% qualifying as “other,” as in other than white. L.A.’s police department has started to mirror the constituency it serves.

When Bratton steps down Saturday, Assistant Chief Earl Paysinger, Director of Office and Operations will be the highest-ranking African American in the Department. Along with Paysinger, there are about 21 other African Americans in the command staff including three female captains.

“There’s a very good group of candidates who have all been a part of helping to bring about the change in the department that’s reflective today. I want to see someone who, like myself, is an optimist and feels good about creating change,” Chief Bratton surmised. “I want somebody who likes challenges, and to confront crisis and challenges. I think ‘they’ have to be a very good people person. This is often reinforced in my conversations with African American leadership, among my own people, and with African American politicians; that they really do believe that they can tell if someone is giving them a song and a dance… if they’re not sincere. And so, the next chief is going to really have to be able to, not only talk the talk, but they are going to have to be able to show that they can walk the walk, otherwise they’re going to very quickly be discovered that they’re only going through the motions. The good news is that all of the people on my command staff have been walking the walk with me. I haven’t been doing this by myself. I want to see someone who believes as I do that police can be used to effectively reduce racial tensions instead of exacerbating it and making it worse.”

The Los Angeles Police Commission has chosen the three finalists in the campaign to become the next chief: Assistant. Chief Jim McDonnell, Deputy Chief Charlie Beck and Deputy Chief Michel Moore. Mayor Antonio Villaraigosa is scheduled to conduct interviews with the three and plans to announce his choice for chief on Monday. The City Council then must ratify Villaraigosa’s choice. A decision is not expected to take place before Nov. 10. Deputy Chief Michael Downing has been appointed as the interim chief until a permanent replacement is selected and ratified.