We cannot say it too often, stress it too much and certainly must never downplay in any way the definitive, determining and decisive role the principle and practice of righteous and relentless struggle have played in the self-conception, self-construction and self-assertion of our people and our organization Us, and the persons called into being and cultivated by both. For among the most defining features of our people is that we are a culture of righteous and relentless struggle, earnest and ongoing struggle to free ourselves and be ourselves, secure justice, expand the realm of human freedom, and build the good community, society and world we and all humans want and deserve to live in. And so it is good to reach back to retrieve and reflect on the lessons of our lives, work and struggle in order to deepen our understanding and constantly improve our practice.

Even without understanding it in the depth that would come later, we were in, 1965, a new generation building on centuries of sacrifice and struggles of all those who preceded us, those who cleared firm and sacred ground on which we stood and still stand and who opened essential and upward ways on which we would continue the unfinished struggle for liberation and ever higher levels of human life. In speaking of this history, Mary McLeod Bethune told us we are heirs and custodians of a great legacy,” but we were not always able to recognize and rightfully respect the historical and cultural ties of life and struggle that bound us with each preceding generation. We could readily give those ancient and absent credit, i.e., our ancestors; but the immediate and living preceding generation was a focus of much of our criticism, although we eventually balanced our critique and began to work cooperatively with them. In a word, we were compelled by both the heavy hand of reality and righteous reasoning to see and accept the need for intergenerational collaboration, cooperation and collective struggle.

There were many reasons for our critique of established order-leaning leadership and cautious counsel, especially our need to find our own way, develop our own voice, and pose our own vision of what we as a generation should be about. We embraced Fanon’s classic statement that “Each generation must out of relative obscurity, discover its mission and fulfill it or betray it.” And we read it as our need to discover in the rich resource of our life and culture new, good and rightful ways forward. Part of this critique of the preceding generation in “responsible” positions was also because they often counselled caution and restraint which we deemed inadequate at best and at worst, only in the interest of the oppressor.

Malcolm X had taught us that being responsible to the people must be contrasted with being “responsible” in the eyes of the oppressor. For he said, “You’ll always be a slave as long as you’re trying to be responsible and respectable in the eyesight of your master.” On the contrary, “when you’re in the eyesight of your (oppressor), you’ve got to let him know you’re irresponsible,” and this indeed, in audacious and outrageous resistance. Furthermore, we were in a hurry and too determined, young, righteously angry and impatient to consider thoroughly the time it takes to build, to mobilize, and to organize the people in a massive revolutionary movement forward that could sustain itself thru the vicissitudes and delayed victory history would hold for us.

So we forged ahead, not always learning the lessons from those whose experience and wisdom could accelerate both our development and the liberational project to which we and they were committed. Even after reading Fanon, we again did not give enough weight to his counsel that “We must rid ourselves of the habit, now that we are in the thick of the fight, of minimizing the actions of our parents.” For “They fought as well as they could with the arms they possessed then.” And, of course, it is their struggles which brought us to this point. Moreover, it was our task not to deny their achievement, but to learn from it, build on it and take things further, as they did in their times. And now in sober reflection on our history, we hope and believe we did.

Fanon had also taught us not to confuse spontaneous revolt with revolutionary struggle and that we must have a long view of history and the future, and at every step and stage be concerned with sustainability, with the capacity to be resilient, resourceful and undefeatable. For given the asymmetrical balance of forces and power and the guerilla nature of the struggle we wage, a priority aim is not to defeat the enemy-oppressor in one brief or major battle, but to avoid being defeated ourselves and to seize every opportunity to advance the struggle. Indeed, every day we stay alive and remain in resistance, it is a defeat of the oppressor’s evil intentions to defeat and destroy us. Every day, we are not dispirited or diverted, or divided by smaller identities that defend themselves rather than our people as a whole, we are not defeated, but have turned the evil intentions of the oppressor into ashes in his mouth and agony in his mind.

Relevant here also are Fanon’s lessons on the strength and weakness of spontaneity which mark every spontaneous revolt—from those on the plantation to those in our occupied communities, from the killing fields of the Holocaust of enslavement to the battlefields we call Ferguson, Flint, Baltimore and Baton Rouge. It is also a special lesson from Watts and all the other revolts since the 60s, i.e., the need to quickly find ways to sustain the struggle, to keep the fire burning and the light bright and the people on course, on point and above all, together in revolutionary consciousness, commitment and struggle.

Thus, Fanon tells us “the success of the struggle presupposes clear objectives, a definite methodology and above all the need for the masses of people to realize the temporary dynamic character of their efforts.” Here Fanon means that the masses, righteously angry and courageously confrontational in the streets, must move quickly to build an organized Movement which includes all, coordinates and directs efforts and provides the people with a unified leadership, position and program to take the struggle down the long, difficult, demanding and dangerous road, leading to real, radical and revolutionary change.

Fanon tells and teaches us, then, “You can hold out for three days—maybe even for three months—on the strength of the righteous resentment held by the masses, but you will not win a national war; you will not overthrow the terrible machine of the enemy; and you won’t transform human beings, if you forget to raise the consciousness of those in struggle. (For) Neither stubborn courage nor beautiful slogans are enough.” These are reflections not only from over a half century of work, service, struggle and institution-building of our organization Us, but also from a history, culture and people of righteous and relentless struggle, dedicated to radical transformation of society and the world, as well as ourselves—and always, as our ancestors taught us, to bringing and sustaining Good in the world.

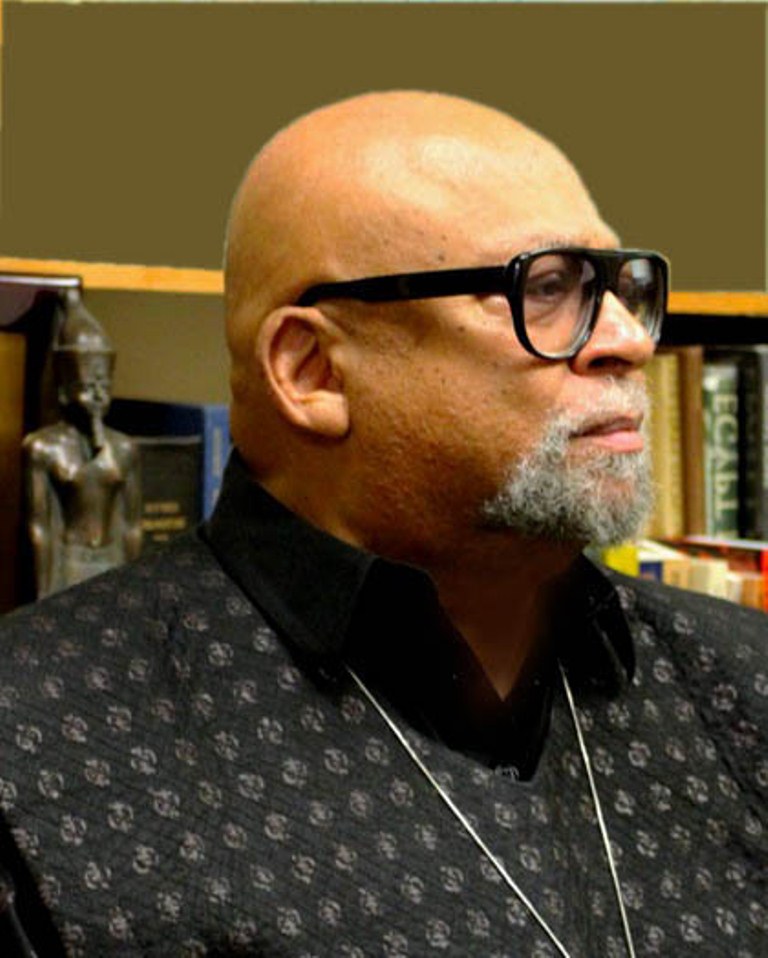

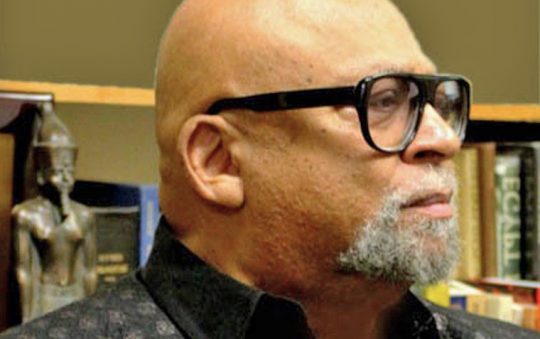

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.