As the edges of the years meet and merge and this year becomes the next New Year, we are asked by our honored ancestors and obligated by the urgencies of our times to pause and ponder the critical questions and issues confronting us, all African peoples, and the world. And we are to do this with parallel questioning and consideration of who we are, what we are to do because of who we are, and how we are to do what we must do because of who we are.

This we call in Kawaida philosophy being decisively clear about our identity, purpose and direction which are interrelated and inseparable. Indeed, on the last day of Kwanzaa, January 1st, Siku ya Taamuli, the Day of Meditation, we are to sit down and engage in deep and focused reflection on being African in the world.

And in this reflection, we are to measure ourselves in the mirror of the best of our history and culture and make a sober and honest assessment of where and how we stand and then recommit ourselves to the excellence and agency for good in and for the world this calls for, encourages, and requires.

As the Kawaida tradition teaches us, in this process and practice, we are to ask and answer three fundamental questions: who I am; am I really who I am; and am I all I ought to be. To identify and define ourselves is not as easy as it might seem. For it can be seen as simply saying one’s name or sex, gender, sexuality, profession, or any of the other identities by which we have come to define and discuss ourselves.

But these identities alone would be to imagine ourselves outside our history and culture and to act as if we are anonymous American ethnics without a history, culture, and the defining particularity of our peoplehood. For in a larger sense, we are not simply our various other identities, but rather we are African, Black, first and belong to a culture and history we cannot easily deny or step out of as Dr. Molefi Asante reminds us. It is our particularity in the midst of the universality of being human in the world. Indeed, African is our unique and equally valid and valuable way of being human in the world.

To ask and answer the question “who am I,” then, is to locate ourselves in the process of our history and the practice of our culture. For we come into consciousness of our expanded sense of self by what we do and aspire to in our community and the world. And those doings and aspirings, rightly defined and developed, are rooted in the best of what it means to be African and human in the world.

It is to place, understand and assert ourselves in the midst of a history and struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves, live good, productive and meaningful lives and contribute to an ever-expanding realm of African and human good and the well-being of the world and all in it. The Husia teaches us that we must know and assert ourselves in the most good and meaningful ways as bearers of dignity and divinity and embrace our ancestors as models to emulate and mirrors by which we measure ourselves.

To answer the question of “am I really who I am” calls for us not to misrepresent ourselves as Africans, not to mask or mutilate ourselves to appease or seek the approval of others, especially our oppressors. It means recognizing and respecting our unique and equally valid and valuable way of being human in the world as Africans, Black people. Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune teaches us, “We are the custodians as well as heirs of a great civilization (and) have given something to the world as a race” and thus, we must be and “are fully conscious of our place in the total picture of mankind’s development.”

Likewise, Nana Frantz Fanon, author of “Black Skin, White Masks,” tells us that many among us too often wear the white masks because of the severity and savagery of our oppression and our quest not to be penalized, punished or oppressed for what Nana W.E.B. DuBois termed our “unforgiveable Blackness” in a racist society. For as Nana Haji Malcolm X taught, the oppressor has problematized and made hateful our bodies and being “from the top of our heads to the soles of our feet.”

And as Kawaida teaches, this problematization of our being through the pathology and savagery of racial oppression causes too many of us to doubt ourselves, deny ourselves, condemn ourselves and mutilate ourselves, psychologically and physically, trying to please, look like and be acceptable to those who caused and cultivated the pathology in many of us. Also, to answer the question of “am I really who I am” is to know and live our lives knowing there is no people more divinely chosen, elect or worthy of life, freedom and justice than we are. It is to walk through life rejoicing in the beauty, sacredness and soulfulness of ourselves, ripping off masks and disguises if we have them and refusing to wear them regardless.

Finally, to answer the question of “am I all I ought to be” is to affirm the fundamental understanding that African means excellence. Indeed, it is to learn the lessons of our history and emulate and extract from them the spirit of possibility and ceaseless striving and struggle, and models of human excellence and achievement.

And in this emulation of the excellence and achievement of our honored ancestors, it means constantly committing ourselves to the struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves, and to create an expansive realm of good, meaning and beauty in the world in the interest of African and human good and the well-being of the world.

Ultimately, it means being honestly, but humbly, able to say as the Husia teaches us: May it be said of me as Rediu Khnum says, “I know myself as a vanguard of the people, a precious staff of the Divine, one who has been endowed with excellence in planning and great nobility of performance.”

Moreover, may it be said of me, “I am dignified, open-handed, pleasant in manner, noble in appearance, godly to behold. One who is kind hearted, open minded, clear thinking, a person of character spoken of with love by the people and highly respected.”

Here we speak of and uphold a legacy of self-knowledge and self-appreciation and always a self-conscious practice that expresses and proves it. For we, as always, know and affirm that practice proves and makes possible everything. Thus, in this unfolding New Year, may it be said of us that we lived a life of love and struggle, loving the people and the good, and striving and struggling constantly to serve the people and achieve and share the good.

May it be said too that we knew and know ourselves as a critical moral and social vanguard in this country and the world. Indeed, it is we African people who must be in the vanguard and at the center of those who resist the Orwellian world where oppressors shamelessly pass themselves off as victims, deny genocide as they commit it and massively kill the innocent and vulnerable and call it self-defense and in defense of a savagery masquerading as civilization.

This is said not without knowledge of how the oppressor cultivates compliance and commands silence and inaction in the face of evil and injustice through fear, funds and favor. But our ethical tradition teaches and demands that regardless, we are obligated to bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place among the voiceless, devalued, downtrodden and oppressed.

For we live in difficult, dangerous and demanding times and we must keep the faith and hold the line in the ongoing struggle for the constant expansion of an inclusive good in the world. And as we continuously say, we are called by the moral imperative of our culture, the pressing needs of our people, and the urgencies of our time to constantly struggle to bring good in the world and not let any good be lost as the Odu Ifa teaches us.

Thus, our honored ancestors call us across the millennia saying: Continue the struggle. Keep the faith. Hold the line. Love our people and each other. Practice the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles. Seek and speak truth. Do and demand justice. Be constantly concerned with the well-being of the world and all in it.

And dare help rebuild the overarching movement that prefigures and makes possible the good world we all want and deserve to live in, and leave as a legacy worthy of the name and history African.

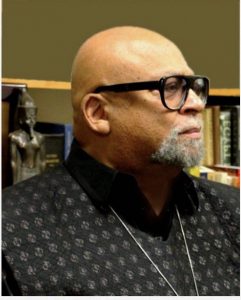

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org, www.MaulanaKarenga.org; www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.Us-Organization.org.