At this hour of urgency and needed liberative initiatives in African and human history, and in this month, Black August, the site and source of such instructive memory and intensified movement, the name, life and legacy of Nana Marcus Garvey looms large as a model and mirror for our assessing and achieving our liberational goals in moving ahead in these rough and exacting times.

Nana Garvey’s central message and mission was/is the retrieval, redemption and liberation of African peoples all over the world. For Africa, for him, was not only a continent, but also a world community.

Nana Garvey was a pan-Africanist, one dedicated to the liberation and upliftment of African people everywhere, to their freedom and flourishing and coming into the fullness of themselves. His pan-Africanism, thus, was not only an irreversible commitment to free continental Africa and its peoples, but also global Africa, the world community of African peoples everywhere.

It is in this spirit and active commitment that he makes his classic battle call, “Up you mighty race you can accomplish what you will.” Here race is not Europe’s racist, inhuman and imposed conception of race, i.e., a category of social status and human worth using Europeans or Whites as a model.

Nana Garvey’s use is an expansive concept of peoplehood, both national and international, both continental and diasporic, in a word, a global, world-encompassing peoplehood concept, a historically evolved and embraced identity and a social reality. It is in this understanding that we call ourselves Africans, not simply descendants of Africans, for all Africans are descendants of the original Africans, our ancestors.

To practice pan-Africanism with Nana Garvey, then, is as he taught, to commit oneself in mind, body and soul to the radical and redemptive project of the liberation and upliftment of African people on the continent and throughout the world, everywhere, on every continent and in every country in the world. It is, he says, to “give back to Africa the liberty (freedom) that she once enjoyed hundreds of years before her sons and daughters were taken from her shores and brought in chains to this western world” and other parts of the world. Thus, he says, “I know no national boundaries where (Black people) is concerned. The whole world is my province until Africa is free,” the continent and global Africa, the world African community.

Nana Garvey then wants us to retrieve and rebuild ourselves to regain the freedom that was violently and viciously interrupted and appropriated, a freedom we had before colonialism, the Holocaust of enslavement and the imperialist plundering and pillaging of our lives, lands and human and natural resources. Master teacher Garvey teaches us we must realize fully and act decisively on the reality that “Man’s first duty is to discover himself.”

This primary and priority emphasis on our obligation to know ourselves means to know our history, to know our current conditions, potential and possibilities and to imagine a world and future worthy of the name and history African and struggle mightily to bring it into being.

“It is the duty of every man (and woman) to find his (her) place, to know his (her) work”, he says. Here, Nana Garvey tells and teaches us that to achieve our place and to do our work, we must question ourselves asking “Who am I here?” in this place, at this time and “What is expected of me by my God and my people?” Nana Garvey foregrounds the centrality of rightful attentiveness to the Divine and our people as ways to give a spiritual and ethical dimension to our sensibilities, thought and practice, to the way we struggle and work our will in the world. He does not want us to be selfish, self-centered in narrow and negative, vulgarly individualist in ways that “take you no further than yourself.”

Indeed, he wants us to honor the Divine in us, to pursue “the ends you serve that are for all, in common, (and) will take you into eternity.” In a word, we are to emulate our Creator, not our oppressor. Thus, he says, stressing our obligation to be world-constructing like the Creator rather than world-destructive like our oppressor, “You must realize that your function is to create, and if you think about it the proper way, you will find work to do.”

And that work is the work of striving and struggle; of building and caring for our people; establishing institutions that house, define, defend and advance our interests; and doing the work to remould and remake ourselves as we struggle for African and human freedom, justice and good in the world.

Nana Garvey tells us that in the process and practice of radical redemption, we must be about the work of liberating our hearts and minds, as well as our bodies, from the history and current conditions of oppression. For liberating the mind is a precondition for waging a victorious struggle to liberate the body. As he teaches, “Liberate the minds of men (and women) and ultimately you will liberate the bodies of men (and women).”

Indeed, as Kawaida teaches, the beginning and continuing battle we fight in the liberation struggle is the battle to win the hearts and minds of our people, and until and unless we liberate the hearts and minds, liberation is not only impossible, it’s also unthinkable. Thus, repeatedly, Nana Garvey urges us in various ways to “remould (ourselves), remake ourselves mentally and spiritually,” otherwise, we remain colonized, enslaved and pretending a freedom we have not yet achieved.

Nana Garvey teaches and tells us, we are called, as we say, by history and heaven to be “co-workers in the cause of African Redemption.” For Nana Garvey, redemption is a multiple meaning and inclusive concept and practice. It speaks to the meaning of saving ourselves, righteously rescuing ourselves, from the pathology of oppression in all its savage, subtle and seductive forms, its domination, deprivation and degradation of us.

And it means regaining our freedom, what he calls “an unfettered freedom,” that carries with it a responsibility for a righteous and relentless striving and struggle to bring, sustain and increase a shared and inclusive good in the world. It means also regaining our lives, our lands, our natural resources, the material basis for living and pursuing a good and meaningful life and coming into the fullness of ourselves as African persons and peoples. It means too reparations, repairing, renewing and remaking ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, renewing and remaking the world.

In this hour of urgency, this historical moment and month of intensified work and struggle, Nana Garvey speaks pointedly and powerfully to us saying, “the time has come for those of us who have the vision of the future to inspire our people to closer kinship, to closer love of self,” our African selves, sufficient in our humanity and the sacredness of ourselves. And we must do this he says in building pan-Africanism, uniting in a liberating practice in the interest of African and human good and the well-being of the world and all in it.

We speak here, he teaches us, of pan-Africanism as an active solidarity in work and struggle that binds us together “into one mighty bond so that we can successfully pilot our way through the avenues of opposition and the oceans of difficulties that seem to confront us.”

And it also speaks of pan-Africanism as an active commitment to a liberative vision and project of Africa, global Africa, the world community of African peoples, doing good in and for ourselves and the world, cultivating and promoting freedom, “human justice, love and equity,” and working tirelessly for African and human good and the well-being of the world, “causing a new light to dawn upon the human race.”

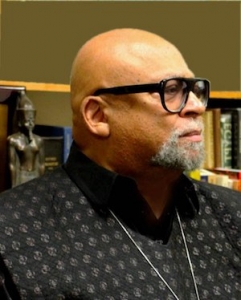

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.