Nana Gwen Brooks was an internationally recognized and respected poet, Poet Laureate and Pulitzer Prize recipient when she decided to join the Black Revolt sweeping the country and calling all Black people to be themselves and free themselves and create an expanded realm of freedom in this country and the world.

She embraced a fundamental tenet of Kawaida philosophy that I put forth in the 1960s that “the fact that we are Black is our ultimate reality.” She writes that “the huge, the pungent object of our prime out-ride/ is to Comprehend/ to salute and love the fact that we are Black/ which is our ‘Ultimate Reality.’”

It is our source and sanctuary, the foundation and framework on which and within which we strive to be ourselves and free ourselves and speak our own special cultural truth to the world.

She wants us to embrace ourselves and each other, see ourselves in expanded and uplifting ways and find ourselves ever resistant and resilient regardless of the times and tests we face. She tells us to reject the negativism of “the down-keepers, the sunslappers, the self-soilers, the harmonyhushers.” And to say to them “even if you aren’t ready for day/ it cannot always be night.” We must, she teaches us, call for the day, hurry the dawn, and as we say in Kawaida, “lift up the light that lasts.”

She reminds us of our capacity and courage, telling us we can change the course of history and rivers. Calling to us, she says “my people, Black and Black… say that the river turns and turn the river.” We have to prepare to meet the hell and hurricanes of history she says, “the brash and terrible weather/ the pains, the bruising…”, the chaos and killing, the evil and unjust.

And we must resist and be resilient above all, we must dare to live in spite of the lynchers and liars, the police and politicians, the systemic violence, the injustice and genocide. For “this is the urgency! Live and have your blooming in the noise of the whirlwind.”

Furthermore, Nana Brooks tells us that we must build our churches, our homes, our mosques and temples and all our institutions, not with brick, steel and stone alone, but “with love like lion-eyes, with love like morningrise. With love like Black, our Black-luminously indiscreet, complete; continuous.” We must “straddle the whirlwind;” we must choose life, “live and go out, define and medicate the whirlwind.”

And again, we must love and serve our people, honor and respect them, realizing that “a garbage man is dignified as any diplomat” and that the ordinary everyday woman “Big Bessie…stands-bigly-under the unruly scrutiny” and “is a moment of highest quality; admirable. Also, Nana Brooks tells us that diligently pursuing the upward path of our people and our culture may bring us a certain sense of loneliness, and in times of crisis and fierce struggle, we might notice that absence, inactivity and silence of others.

Thus, she says, “It is lonesome, yes. For we are the last of the loud.” And yet, we must live, dare to struggle, dare to win and dare to be ourselves and free ourselves. And this means again, we must “conduct our blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind.” For this again reveals and reaffirms the meaning and value of our resistance and resilience.

Nana Nannie Burroughs, educator and teacher, institution builder, womanist, spiritual and moral leader, human rights activist and businesswoman concerned with workers’ rights and unionization, teaches us in word and deed to understand and assert ourselves as a people who “specialize in the wholly impossible.”

As a womanist, Nana Burroughs stressed the equal dignity and rights of Black women and advocated for them to enter the world equally educated and prepared for life and struggle. Like Nana W. E. B. DuBois and other leaders and thinkers of this time and mind, she advocated and practiced an education that teaches students not only how to make a living, but also and equally important, how to make a life.

Thus, she says, “The training of (Black) women is absolutely necessary, not only for their own salvation and the salvation of the race, but because the hour in which we live demands it. If we lose sight of the demands of the hour we blight our hope of progress.” Here, she asks for the cultivation of a social consciousness attuned to the demands of the times, the urgencies of the historical moment in which we live, strive and struggle. Doing this, we are not to lose sight or sense of ourselves or our community and its pressing needs and interests, but to place and pursue them in the context of our times.

Nana Burroughs understands her people as second to none in their soulfulness and sacredness. Indeed, she says, “No race is richer in soul quality and color than the (Black person). Some day he will realize it and glorify them. He will popularize Black.” And she lived to see this come to pass in the 1960s when Nana Elijah Muhammad and Nana Haji Malcolm sacralized, even divinized, Black people.

It is during this time Black people pictured and painted their Lord as Black, created a Black liberation theology, declared they were Black, beautiful, gifted, and proud and called out in radical and righteous resistance, “Liberation is coming from a Black Thing” or Thang, depending on the form of Ebonics we were speaking at the time.

And Nana Burroughs taught unrelenting resistance to all forms of oppression, calling for a total and encompassing victory. She taught that “To struggle and battle and overcome and absolutely defeat every force designed against us is the only way to achieve.” And she urged us to give the best of ourselves to our striving and struggle as a way, not only to free ourselves and be ourselves, but also to honor the work, struggle, sacrifice and achievement of those wayopeners before us.

Thus, she states, “A lot of people endured a lot of hardship, humiliation, suffering and pain. The least I can do is be my best, live my best life, and treat myself and my surroundings with respect.” Also, she teaches, we must always dare to do our best, try regardless of apprehensions and sometimes being unable to do or achieve all we long for or intend.

Nevertheless, she tells us, “Aspire to be, and all that we are not, God will give us credit for trying.” Here, we read her as asking us to step out on faith, Imani, the Seventh Principle of the Nguzo Saba and the foundational principle of all our ancient and ongoing spiritual traditions.

Finally, Nana Burroughs established as the motto of her school the audacious claim and commitment that “We specialize in the wholly impossible.” Now this concept of the “impossible” has at least three possible meanings: the impossible the oppressor and his system teach; the impossible we mistakenly define for ourselves; and the impossible that conceals the possible within it and challenges us to unmask it, make it visible and then pursue and achieve it.

But again, we can only achieve the wholly impossible, Nana Burroughs teaches us, by being our best, living our best, aspiring to and achieving our best and treating ourselves, others and our surrounding with rightful respect.

Riding the storms with Nana Thurman, blooming in the noise and whip of the whirlwind with Nana Brooks, and specializing in the wholly impossible with Nana Burroughs are central and continuing lessons and life realities of our history, an urgent need of our present and a righteous and reliable promise of our future.

And they are left for us as a legacy to be lived, uplifted and passed on as a model and mirror to future generations for this and all the other storms we will have to ride, all the whirlwinds we will have to bloom in, and all the impossibilities we will have to specialize in and achieve.

And as always and again, this is our duty: to know our past and honor it; to engage the present and improve it, and to imagine a whole new future and forge it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.

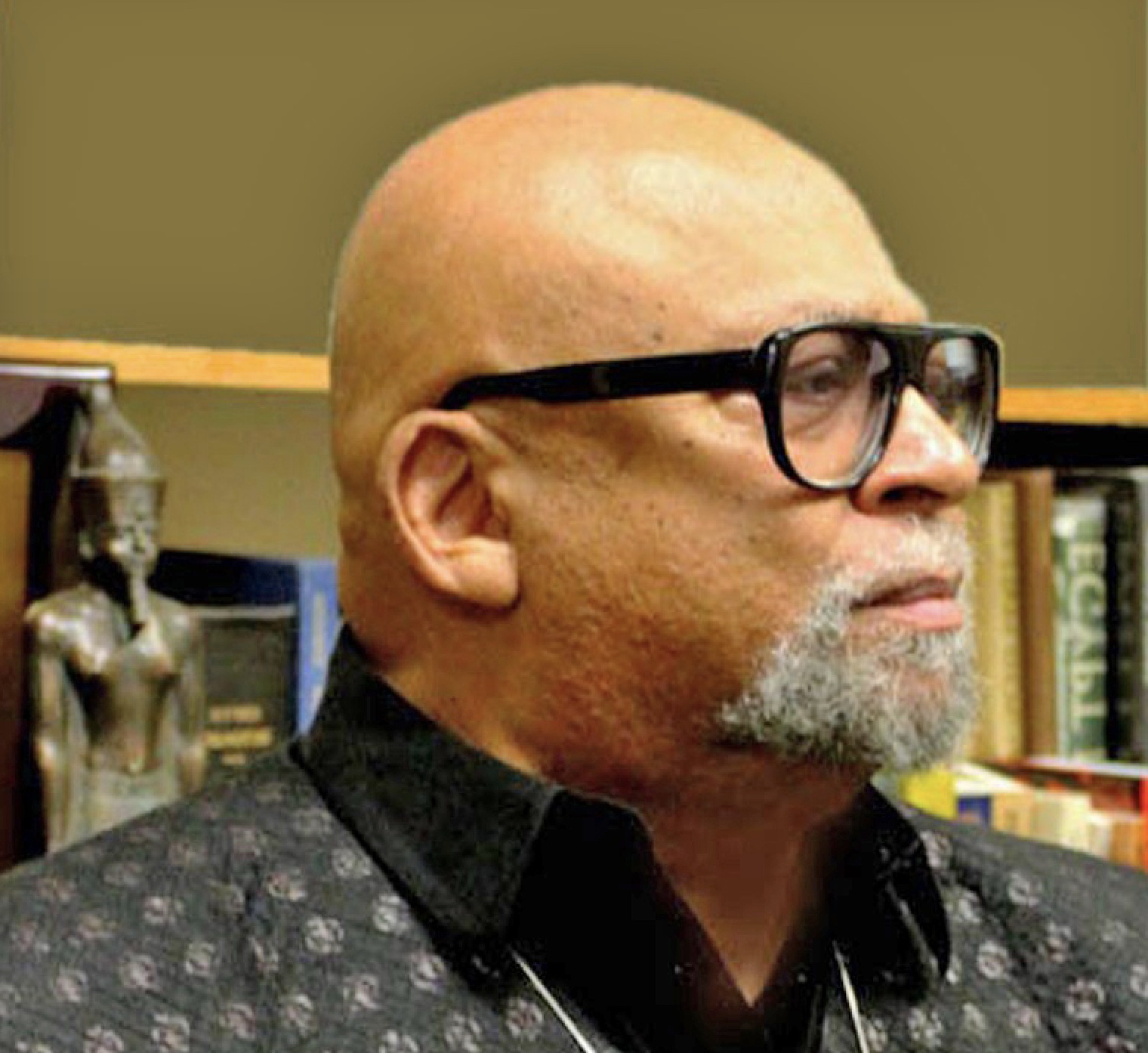

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.