The New Year, as always, no doubt found many of us joining in the larger society ritual of resolution-making which is more an expression of habit and hope than rightful reflection and steadfast resolve. Moreover, it is often essentially personal without proper linkage to the larger issues of community, society and the world. But for us as African people, there is an obligation rooted in our history and reaffirmed in our struggle, to take a more serious approach to this period and time of turning. As the ancestors said, this is the time when the edges of the years meet and this calls for rightful attentiveness to the health and wholeness of our people and the world and to recommitment and continuing struggle to bring, increase, and sustain good in the world.

It is a fundamental Kawaida contention that we must bear the burden and glory of our history with strength, dignity and determination. Surely, the times ahead of us will demand of us the resourcefulness, resilience and righteous resistance by which we understand and assert ourselves in history and as history, embodied and unfolding. This means, in the language of everyday people, there can be no half-steppin’, no nick namin’ the truth, no spittin’ in the wind to see which way to go. On the contrary, we must be the storm riders and river turners Howard Thurman and Gwen Brooks calls on us to be. And like Harriet Tubman, we must reject individual escape, turn around towards our people, confront our oppressor and oppression and dare continue the difficult and demanding work and struggle to achieve freedom, justice, peace and other goods in and for the world.

Thus, as always, we were to sit down on the last day of Kwanzaa and the first day of the year, the Day of Meditation, and meditate on the awesome meaning and responsibility of being African in the world. Indeed, we are to measure ourselves in the mirror of the best of our culture and history and ask ourselves where do we stand, especially in context of our time? It is an assessment which is both personal and collective and involves asking and answering three basic questions: who am I; am I really who I am; and am I all I ought to be?

The first question is designed to remind us of our identity in the most expansive personal and collective sense, beyond vulgarly individualistic illusions and deficient and deformed group caricatures induced by severe oppression.

The second question is to remind us of the need to constantly reaffirm the realness and wholeness of who we are, to reject the masks and false identities savage oppression often makes many of us wear, and to choose daily to be African in the most expansive and elevating sense. And the third question is meant to encourage us to honor our identity, as revealed in the best of our history and culture, and to strive always to bring forth in our daily practice the best of what it means to be African and human in the fullest sense. After deep reflection on this and related points of focus, we are to recommit ourselves to our highest values and most expansive vision of being African in the world.

One way to approach this ethical obligation is to ask a series of questions about the social and moral meaning of being heirs, representatives and custodians of the awesome legacy of good and greatness left by our ancestors.

There are three modal periods in our history which provide a foundation and framework for this urgent and ongoing self-questioning. These are the periods of classical African civilization in the Nile Valley, the Holocaust of enslavement, and the Reaffirmation of the 60’s. In each we are provided, not only with a source of an expansive self-understanding, but also a foundation and framework for our essential self-questioning and rightful self-assertion in the world.

And so we ask ourselves first, what does it mean to be the fathers and mothers of humanity and human civilization; to have stood up first as the elders of humanity; spoke the first human truth; organized the first family and society; imagined math, art, and astronomy; structured time into measurable components of a calendar; created the architecture of pyramid, obelisk and temple; turned imagination into art, medicine and science; and developed the beauty and challenge of daily life into an art-form alphabet and a life-enhancing literature?

And what does it mean to have introduced to humanity the ideas of humans as the bearers of dignity and divinity; the immortality and judgment of the soul; politics as an ethical vocation; service as the substance of greatness; and character, care for the vulnerable, truth, justice and loving kindness as the cornerstones of the ethical life; and conceived the concept of serudj ta, the ethical obligation to constantly heal, repair, transform and enhance the world thru medicine and moral practice? How does this speak to our spiritual, ethical and social understanding of ourselves and our responsibility to doing Maat (rightness, good) in the world, repairing and making it ever more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it?

We are also to ask ourselves, what does it mean to be sons and daughters of the Holocaust of enslavement, descendants and survivors of this great act of genocide against African people, and gross crime against humanity; this morally monstrous destruction of human life, human culture and human possibility? What does it mean to be descendants of Harriet Tubman, Frederick Douglass, Nat Turner, Nana and Gabriel Prosser, Sojourner Truth, Denmark Vesey, and all the other freedom fighters named and unnamed, who stood up in the midst of silence and savage suppression and dared reject, refuse and resist, and to struggle and stretch the boundaries of freedom for us and humankind? What obligation does it impose on us concerning the ongoing need for us to hold fast to the faith of our fathers and mothers in the good, the right and the possible, to remember and bear constant uncompromising witness to the horror and horribleness of our Holocaust, to raise up the names of those who refused to be dispirited or defeated, and to struggle to repair and heal ourselves through our struggle for justice and our larger struggle to heal, repair and transform the world.

And what does it mean to be authors and heirs of the Reaffirmation of the Sixties, i.e., the reaffirmation of our Africanness and our social justice tradition? What does it mean to have waged and won with our allies, struggles that not only changed the course and character of this country, but also expanded the realm of freedom, inspired and informed other peoples’ movements in this country, and became a model of the struggle for human liberation throughout the world? And what does it mean to be descendants of a generation of giants in the 60’s like Malcolm X, Fannie Lou Hamer, Kwame Nkrumah, Martin King, Jr., Ella Baker, Robert Williams, Rosa Parks, Frantz Fanon, Dorothy Height, Julius Nyerere, Joseph Lowery, and others? And how do we honor their and all our ancestors’ legacy except by living their life-lessons, loving and uplifting our people, and continuing their struggle to expand and secure the realm of human freedom and human flourishing in the world? It is in rightful response to such questions that our new year resolutions acquire deep meaning and undergird our ongoing work of freedom, justice, empowerment of the masses, and enduring peace in the world.

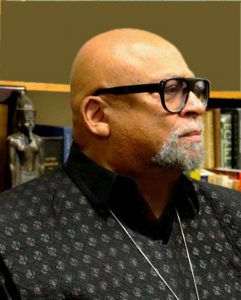

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.