The towering portrait of noted abolitionist Frederick Douglass arrived at Fisk University to great fanfare.

A gift from W.E.B. Du Bois, one of the university’s most famous graduates, the near life-size painting was cause for unfettered celebration when he made the donation in 1959. In a letter to Du Bois, then-President Stephen J. Wright was effusive in his thanks.

“It is certainly a magnificent portrait and I feel that we must unveil it with some kind of appropriate ceremony,” Wright wrote in a Dec. 28, 1959 letter. “We are very grateful to you for this priceless gift.”

But now, more than 50 years later, the prized portrait is gone.

Fisk’s newest leaders say they are not sure what became of the decades-old gift. After a Tennessean inquiry, along with historic documents tracing the painting’s journey from Du Bois’ home in Brooklyn to Nashville, officials at Fisk said they are mounting an intense investigation to find the portrait.

“We welcome any information regarding this portrait as we continue our research that could be helpful in identifying the whereabouts of the Frederick Douglass painting,” Interim President Frank Sims said in a statement. “The university continues to work closely with our legal counsel to resolve this important matter.”

Fisk’s sudden push to pinpoint the whereabouts of the once-treasured painting came as welcome news to Lisa Struckmeyer, a historian who has been searching fruitlessly for answers for three years. Her quest began in 2013 while working as a seasonal ranger and tour guide at the Frederick Douglass home, a National Historic Site in Washington run by the National Park Service.

She was hypnotized by a portrait _ five feet tall, dated 1883 _ that hung in Douglass’ sitting room. In the painting, a gray-haired Douglass stood, eyes glowing, holding a baton.

“The painting is quite stunning,” Struckmeyer said. “I always felt very privileged to be standing in front of it.”

Overcome with curiosity, she set about studying the artist, Sarah James Eddy, and how the portrait came to be. Struckmeyer soon discovered that seemingly simple question was complicated by shadows of history.

Struckmeyer undertook a dogged, years-long search for the Douglass portrait given to Fisk, which she thought of as the missing partner of the painting she had admired in person.

Working alongside researchers at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, where a collection of Du Bois’ letters are archived, Struckmeyer reviewed a trove of documents related to the painting.

There was a letter from Du Bois to Eddy in 1914 in which he asked for the painting, calling it “a most excellent and interesting work.” He promised to rearrange furniture and hang it in a prominent spot “so that the world could have the advantage of it.”

A photograph from around 1946 showed Du Bois at home standing in front of the portrait. In the photo, Du Bois, co-founder of the NAACP and a lifelong activist, matches Douglass’ steady expression.

And in 1959, when Du Bois was 91, he made arrangements to donate the portrait to Fisk, his alma mater. An expert on Du Bois described the gift as a profound gesture to the institution where he first developed a racial identity, one that would shape the rest of his life and American history.

“Frederick Douglass is a symbol of not just freedom but the ability through speech and through oration to tell the story of African-Americans” in a style Du Bois sought to emulate, said Whitney Battle-Baptiste, director of W.E.B. Du Bois Center at the University of Massachusetts Amherst.

Du Bois had the portrait shipped to Fisk in December 1959, and asked the university to include an inscription noting that it was a gift from him and his daughter, also a Fisk graduate.

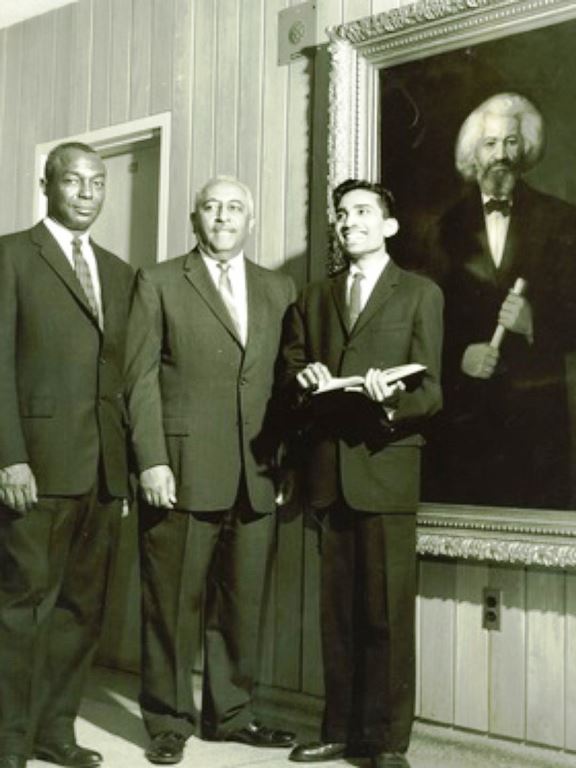

Fisk received the portrait and sent Du Bois a news release that university officials had written to trumpet the painting’s arrival. The release, from May 1960, included the photograph of the top university leaders of the day beaming alongside the portrait in Du Bois Hall. A brief story ran in The Tennessean confirming the painting’s placement and significance.

That is where the paper trail ends.

When Struckmeyer reached out to several leaders at Fisk, some of whom have since left the university, she said she was met with a mixture of surprise and silence. But no answers.

In a letter dated Feb. 14, 2014, which Struckmeyer shared with The Tennessean, former Fisk curator Victor D. Simmons thanked Struckmeyer for bringing the portrait “to our attention,” indicating he was not aware of its existence before she reached out.

Struckmeyer said she never heard back from Simmons.

Frustrated by unanswered emails and looming questions, Struckmeyer with some trepidation reached out to The Tennessean this year.

“I didn’t want to bring bad press on Fisk at all,” Struckmeyer said, a sentiment she echoed several times across multiple interviews.

She shared details of her search for the portrait and her communication with the university in hopes that the added publicity might help unravel the mystery. Her hope, she said, is that the painting is recovered and a new generation of Fisk students might come to appreciate a painting that had such an effect on her.

Her goal, she said, is not to rail against Fisk administrators, but to see the Du Bois’ wishes for the painting honored.

“I want it to find its way back to Fisk. I want it to hang in Du Bois Hall where he wanted it to be,” she said.

“I just want it found and brought back to life there.”