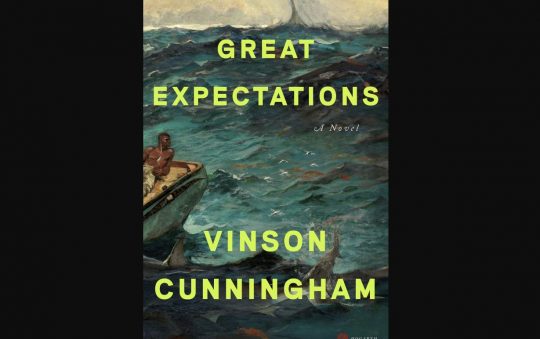

In this March 5, 2016, file photo, Democratic presidential candidate, Hillary Clinton, accompanied by Bishop Corletta Vaughn, speaks with African American ministers, in Detroit. During a primary season that has proved surprisingly competitive, bombarded with persistent critiques about her likeability and trustworthiness, Clinton has maintained a strong bond with one significant block of Democratic Party voters. Black women. (AP Photo/Carlos Osorio)

From the pulpit of an African-American church in Detroit not long ago, Bishop Corletta Vaughn offered a rousing endorsement of Hillary Clinton that went far beyond politics.

With a smiling Clinton sitting a few feet away in the purple-walled Holy Ghost Cathedral, Vaughn said she had seen Clinton “take a licking and keep on ticking.” Alluding to Bill Clinton’s past infidelity, she added: “I’m not talking about politically. I’m talking about as a wife and a mother. That’s when I said: I love that woman. She taught so many of us as women how to stand in the face of adversity.”

During a primary season in which she has faced surprisingly strong competition and been bombarded with criticism of her trustworthiness, Clinton has maintained a strong bond with one significant bloc of Democratic Party voters. Black women, part of President Barack Obama’s winning coalition in 2008 and 2012, have locked arms behind Clinton, hailing her as a Democratic standard-bearer, survivor and friend.

“That determination and strength, particularly has meaning to African-American women,” said Sharon Reed, 60, a community college teacher from North Charleston, South Carolina. “Who has overcome more obstacles and darts and arrows than she has? And she’s still standing and she’s still strong.”

Though the primary contest is not over, Clinton, the former secretary of state, holds a big delegate lead over Vermont Sen. Bernie Sanders and is considered likely to win the Democratic nomination. African-American women have played a big part: About 8 in 10 across all the states where exit polling has been conducted have voted for her, and in some cases support has been above 90 percent.

Clinton has fared less well with other groups, in particular with younger voters and white men, many of whom have preferred Sanders. But, as in past years, black women are demonstrating that they are motivated. So far, they have made up at least a slightly larger share of the electorate than black men in almost all states with significant black populations, and a significantly larger share in seven of those states.

She’ll need those women in November. When Democrat Obama won the past two elections, he counted on black women’s votes, and he got them. In 2008, some 68 percent voted in the general election, and 70 percent came out in 2012. According to exit polling, the vast majority voted for Obama.

Clinton’s campaign has sought to reinforce these bonds. At black churches and businesses, she has stressed her ties to the popular president and touted endorsements from leaders such as Rep. John Lewis of Georgia, a civil rights icon. She has emphasized issues like criminal justice reform and gun control and is campaigning alongside black women who have lost children to gun violence.

“I really got the sense that she could really relate to us, as being mothers and women and daughters,” said Lucy McBath, whose teenage son Jordan Davis was shot and killed at a Jacksonville, Florida, gas station in 2012. Lucy McBath was part of a group of mothers who met with Clinton privately in the fall and has been out campaigning for her.

These efforts have been headed by LaDavia Drane, who joined the campaign last year as director of African-American outreach. She has sought out female pastors like Vaughn for Clinton’s church visits. She organized the meeting between Clinton and the mothers impacted by gun violence. And she has worked to establish grass-roots networks for black women such “Heels for Hillary” in cities around the country.

Drane described Clinton’s connection to mothers, particularly black mothers, as “a secret sauce, it’s a match made in heaven.”

Before black audiences, Clinton appears at ease. At the Detroit church, she opened up about her personal struggles.

“What has always guided me and supported me has been my faith,” she said. She recalled the parable of the prodigal son and seemed to reference her husband, now diligently campaigning for her. “When someone who has disappointed you, who has often disappointed themselves, decides to come home, it is human nature to say you’re not wanted … but that’s not what the father in this parable did.”

Evelyn Simien, a professor at the University of Connecticut who studies black voting patterns, said Clinton’s outreach has been savvy. But she also stressed that black women have long been active Democratic voters and they know Clinton far better than Sanders. She said this year’s support is not just about personal connection, but that “it comes down to politics and the issues.”

Clinton’s close relationships with black women date back to one of her first political mentors, Marian Wright Edelman, the founder of the Children’s Defense Fund. Black women have held top positions with Clinton over the years, including Maggie Williams, who was chief of staff when Clinton was first lady, and Cheryl Mills, chief of staff when she was secretary of state. In the current campaign, black women are in key roles, including senior spokeswoman Karen Finney and senior policy adviser Maya Harris. Strategist Minyon Moore has long served as an outside consultant.

“I feel a kinship to who she is. She knows and understands the battle that we fight every day,” said Ohio Congresswoman Marcia Fudge, a past chairwoman of the Congressional Black Caucus. “She has a special place for us because she really gets it.”