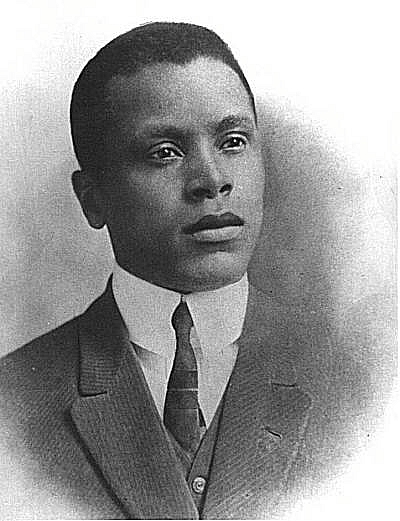

William M. Trotter

Media Pioneers

“They chronicled the Black experience in different ways; print & film”

William Monroe Trotter

Civil Rights Activist and Journalist

Sunrise: April 7, 1872–Sunset: April 7, 1934

William Monroe Trotter was born in Chillicothe, Ohio to James Munroe Trotter, and Virginia Isaac Trotter. No information was found about his adolescent years, but he was an honor student in Hyde Park High School where he graduated in 1890. He went to Harvard University where he received his bachelor’s degree magna cum laude and he was elected to the Phi Beta Kappa fraternity during his junior year.

Trotter started working himself as an insurance agent, a real estate broker and then gradually moved into mortgage funding. His early career choices were merely stepping stones towards his real passion–that of publishing his own newspaper. He experienced much prejudice in his early career and his choice to leave was an easy one. He married Geraldine Louise Pindell on June 27, 1899 and in 1901, he founded the Boston Guardian to urge Black people stay on the front lines in defense of their rights. The publication took a strong stand against discrimination based on color and the treatment of Blacks as second-class citizens.

As the Guardian became a successful national newspaper, Trotter’s name and his national stature rose with it. He was often called upon to speak before large audiences and had unfettered access to the White House. He joined W.E.B. Dubois in forming the Niagara Movement, the forerunner of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); however, Trotter objected to any White financing or leadership for the new organization. The newly-formed organization and the recently-founded publication formed a natural partnership fighting for the same causes and traveling parallel paths of protest.

He was vocal, outspoken and considerably militant for his time. Trotter and a group of his followers disrupted a gathering where Booker T. Washington was the main speaker. He was sentenced to 30 days in jail for allegedly throwing a stink bomb into the crowd.

Trotter opposed Washington’s moderate positions and compromises, by publicly denouncing Washington, who believed Blacks should find ways to “get along with their White oppressors;” who believed that intolerable racial conditions were actually improving; and who promoted manual and industrial training for Blacks over traditional forms of education. He (Trotter) also protested Marcus Garvey’s militant back-to-Africa movement as being harmful to “real” advancement for Blacks.

He understood the power and persuasion of the press, and sought to use his “pen” to contain some of the “swords” of his day. He reportedly went to see President Woodrow Wilson–whom he had supported for the presidency–to confront him and to extract some measure of benefit for Black people. Trotter specifically wanted to know where Wilson stood with regards to lynching and segregation, and he pressed the President for an answer. According to Trotter, Wilson said, “Segregation is not humiliating, and your manner offends me.” The encounter made the front page of the New York Times. Trotter was castigated as a traitor to his race by some and by others, he was praised for his fearlessness and unselfish devotion to the higher interests of the “negro” race.

In 1919, he applied for a passport and was denied because of his highly publicized disagreement with the President. He wanted to place the ‘negro” question before the League of Nations. He surreptitiously obtained a job on a transatlantic steamer and appeared at the conference as a delegate of the National Equal Rights League. But his petition was not heard because the heads of state including the President of the United States refused to include it in any proviso or on the agenda.

Trotter returned to the U.S. and though penniless, he spent the rest of his life as a crusader for total equality. He had devoted all his resources to fight against racial discrimination and he died having paved the way for Black leaders and Black people to enjoy a better quality of life. He died on his 62nd birthday.

Oscar Micheaux

Pioneer Film maker

Sunrise: 1884–Sunset: 1951

Oscar Micheaux was born in Metropolis, Illinois, the fifth child in a family of thirteen. No information was found about his parents, however, while in his teenage years, he worked as a farm laborer before migrating to Chicago. There, he worked as a shoeshine boy and Pullman porter. He was confident, and so self-assured that in 1905, attracted by the lure of the government, he invested his savings in inexpensive farmland in South Dakota and became a homesteader. It was in an all-white community that turned out to be 320 acres of parched dirt. In addition, he had no farming experience, but he learned quickly by observing and talking to his neighbors, and studying their farming techniques closely.

In 1910, he married Orlean McCracken, a minister’s daughter from Chicago and she joined him on his farm. The rigors of being a farmer’s wife took a toll on her and after losing their first child during labor, she moved back to Chicago. Micheaux and his father-in-law already did not have a good relationship and this worsened it. As Micheaux began writing and making films, his father-in-law would often become a focal point in some of his literary works and films.

While he was farming, he published and distributed his first novel, “the Conquest” in 1913; it was a semi-autobiographical story and he sold it door-to-door mostly to farmers. At the same time, a drought hit the South Dakota plains and Micheaux eventually lost his farm but despite his personal loss, he enjoyed the freedom that his entrepreneurial spirit and self-reliance brought him. By 1917, he had written two more novels: “the Forged Note” and “the Homesteader”; the latter became the first full-length film written, produced and directed by a Black person. It was a success when it grossed over $5,000 and placed the Micheaux name in history.

The Lincoln Company in Nebraska had offered to film the Homesteader, but there were too many conditions and restrictions, and that prompted Micheaux to found his own company, the Micheaux Book and Film Company, where he could portray Blacks realistically relative to the contemporary issues of the day–from lynching in the South to socializing in Harlem in the North.

Micheaux began working tirelessly devoting all of his time, efforts and energy to all the aspects of movie making: writing, producing, directing and distributing every film that he made. In one year’s time, he had made three films that earned him $40,000, thanks to the promotional techniques he had developed for himself. He would go from city-to-city by car carrying his own films and dealing directly with the owners of theatres in the Black community, which was his primary market at that time.

He was determined and relentless in his frank depictions of Black life and off-limit, taboo subjects. In 1919, Micheaux made “Within Our Gates,” to counteract the negative impact of D.W. Griffith’s “the Birth of a Nation” that was hailed by Whites as a masterpiece. Then in 1924, he teamed with another great, Paul Robeson, to make “Body and Soul and made his first movie with sound, “the Exile” in 1931. Throughout his career as a film maker, Micheaux made over 40 movies and left a body of work unparallel when measured in the context of the time and circumstances under which he performed his craft.

He died at the age of 67 and was survived by his second wife, Alice Micheaux. They were married in 1926 and she had acted in several of his movies.

The Directors Guild of America honored Oscar Micheaux posthumously with the Golden Jubilee Award; the Oscar Micheaux Festival is held annually in Gregory, South Dakota; the Oscar Micheaux Award is presented annually by the Producers Guild of America and in 1990 during “Motown 30,” Denzel Washington paid tribute to Oscar Micheaux when he mentioned Micheaux’s traveling from city-to-city as he distributed his films from the trunk of his car.