In his clear and compelling call to African peoples to continue the liberation struggle, keep the faith and hold the line, Nana Marcus Mosiah Garvey promises to return after death and bring with him “countless millions” of ancestor soldiers to aid our peoples in achieving victory in “the fight for liberty, freedom and life.” And he asked us, as an enduring inspiration, to look for him in the “whirlwind or storm” as a sign of both a covenant and call to struggle.

Measured in the accurate and unfalsified scales of history, Nana Garvey brings a heavy weight and worth in the world in his global pan-African efforts to liberate and uplift African peoples, and his message remains relevant to our current and ongoing struggles. For our essential and enduring struggle is ever to be ourselves and free ourselves, flourish and come into the fullness of ourselves.

Recognizing the world historical importance of Nana Garvey’s and his organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association’s global reach and work, the UN General Assembly chose August 31st , the day the UNIA declared an international day of celebration of African peoples as the UN International Day of People of African Descent.

This day was established by the UNIA at its 1920 Rights Convention in New York where it also issued the Declaration of Negro Rights, stressing the shared human rights and common goods justly and equitably shared by all and especially the right of all peoples to self-determination, self-representation, freedom and justice.

His continuing concerns are African dignity, rights and the redemption of African people, a concept with spiritual, psychological and political implications, including meanings of reclaiming, recovering and rebuilding ourselves and our culture and history, saving and liberating ourselves, developing ourselves and ultimately flourishing and coming into the fullness of ourselves. He holds that acquisition of knowledge of self and the world is a practice of freedom.

Using the concept of emancipation as a synonym of freedom, he urges us to free the African mind from its negative European accretions, saying, “We are going to emancipate ourselves from mental slavery because whilst others might free the body, none but ourselves can free the mind.” Indeed, this self-emancipation of the mind is critical because “The man who is not able to develop and use his mind is bound to be the slave of the other man who uses his mind.”

This is an affirmation that in order to truly free ourselves we must not only free our bodies, but also our minds. One of Nana Garvey’s most illustrious students, Nana Haji Malcolm X, reaffirms this essential understanding, saying that “we must recapture our heritage and our identity if we are to ever liberate ourselves from the bonds of white supremacy. We must launch a cultural revolution to unbrainwash an entire people.” And this contention concerning freeing the mind is also reaffirmed in Nana Frantz Fanon’s statement that the liberation struggle is to achieve “not only the disappearance of colonialism, but also the disappearance of the colonized person.”

In his “Dissertation on Man,” Garvey defined the human person in terms of their capacity for self-formation and self-determination. He states, “Man is the individual who is able to shape his own character, master his own will, direct his own life and shape his own ends.” It is a strong sense of agency reflected in ancient African texts and modern Afrocentric thought such as Molefi Asante’s Afrocentricity, with its stress on agency, victorious consciousness and audacious initiative in the world.

Nana Garvey is ever insistent that it is we, ourselves, who must wage and win the victorious struggle for liberation. Thus, he repeatedly in one form or the other tells us “If you want liberation, you, yourselves, must strike the blow. If you must be free, you must become so through your own efforts.” It is a restatement and reaffirmation of Nana Frederick Douglass’ counsel to the enslaved and oppressed Black people all, during the Civil War. He said, those “who would be free themselves must strike the blow.”

Kawaida philosophy, building on these teachings, asserts that “We are our own liberators and no matter how sincere or numerous our allies are, those who would be free must strike the first, the final and decisive blow.”

Nana Garvey also stresses the need for Black people to be self-authorizing, self-legitimizing and self-determining. He believes in the unquestionable equality of human beings and argues that whatever rights any human beings have are also the rights of others. It is we, he taught, who must decide who is worthy among us of sainthood, to be considered a martyr for the struggle and any other positions of honor and elevated respect. Thus, he says, “we must canonize our own saints, create our own martyrs and elevate to positions of honor Black men and women who have made their distinct contributions to our racial history.”

He foregrounds Nana Sojourner Truth as a saint; Nana Crispus Attucks for being the first to die in the cause of America independence and Nana George William Gordon, a Jamaican radical rebel, executed without due process for resisting British colonialism, as a martyr equal in status and stature to any other martyrs in the world. And he cites Nana Toussaint L’Ouverture, one of the leaders of the Haitian Revolution, as a brilliant “soldier and statesman” of the highest level.

He wants us to “see good and perfection in ourselves.” Here he agrees with Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune and others in terms of our past achievements and the richness of our contribution to world civilization. Dr. Bethune states that “We are custodians as well as heirs of a great civilization. We have given something to the world as a race, and for this we are proud and fully conscious of our place in the total picture of mankind’s development.”

This great civilizational legacy position is expressed in Nana Garvey’s contention that “the world is indebted to us for the benefits of civilization.” He asserts that many modern achievements are “duplicates of a grander civilization that we reflected thousands of years ago, without the advantage of what is buried and still hidden.”

Here he argues that there is a great treasure of knowledge and know-how in various disciplines that remains undiscovered and that can add to the further development of humankind and human society, if we practice sankofa, reaching back and retrieving the best of our achievements and posing them as fruitful options for initiatives in our time.

The aim, then, is not simply to recover historical memory and culture, but to revive that history and culture of excellence and achievement to initiate “a return to it in the rebuilding of Africa.” And here, we speak not only rebuilding the Continent of Africa, but also the liberation and upliftment of the entire world African community in every part of the world.

Finally, Nana Garvey reaffirms the critical importance of the liberational project. He

says, “We declare to the world Africa must be free, that the entire [Black] race must be emancipated…” from all constraints and restrictions on full human freedom. Like Osagyefo Kwame Nkrumah, another of his illustrious students, would also argue later, he wanted Africa liberated to be a self-conscious force for good in the world.

Thus, he asserts that, as in ancient times, “Africa has still its lessons to teach the world. We will teach man the way to life and peace, not by ignoring the rights of our brother, but by giving to everyone his due.” Indeed, “The hand of justice, freedom and liberty shall be extended to all mankind,” ever mindful that “there can be no peace without equity and justice to all mankind.” Clearly this is a critical and compelling lesson and moral imperative for our times.

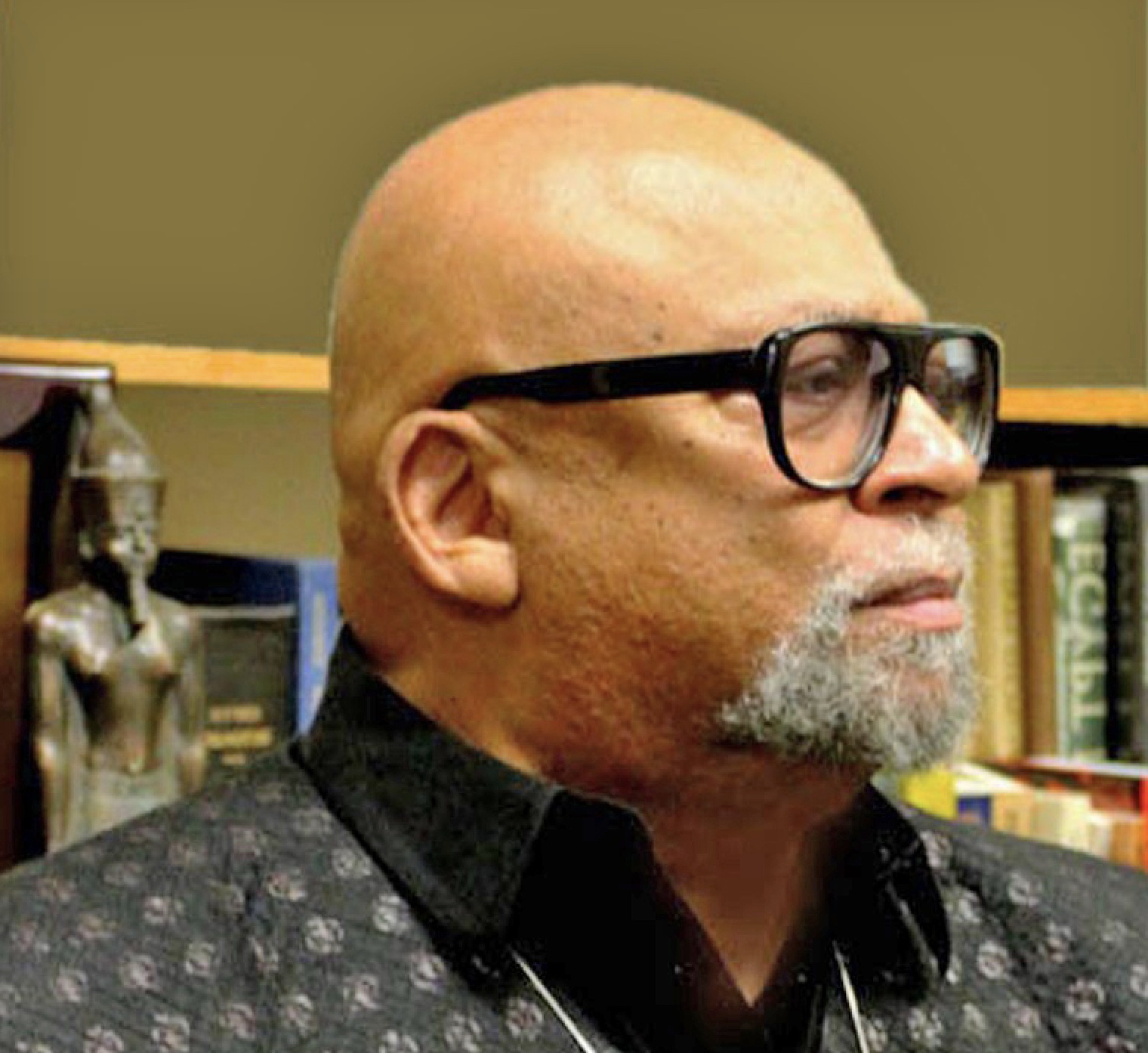

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.