It is Haji Malcolm who taught us that there are signs for those who can, want and have the will to see, and if we read them rightly, there are signs of the times that offer foundational lessons from the past and instructive evidence of an emerging future of renewed mutual caring, community and struggle for us as a people.

I speak here of the solidarity and collective resistance in Montgomery demonstrated by Black people in defense of Damieon Pickett, a Black man, against the unprovoked and unjustifiable aggression by a group of Whites, male and female, attacking him en masse, punching, kicking and cursing him and shouting racist slurs. As he noted, Co-Captain Pickett was just doing his job when he was brutally attacked by Whites at the Montgomery river dock, and Black people walked, ran and swam defiantly to his defense.

Here, again, if it is read rightly, this recent racial confrontation in Montgomery, Alabama, a city and site of fierce struggle, infamy and fame during the Black Freedom Movement, offers us some meaningful messages, signs and sense of things possible together and unfolding in our ongoing shared and collective struggle. And this has added meaning in this month of August dedicated to honoring and recommitting ourselves to our righteous and relentless struggle for freedom, justice and good in the world.

But we must not turn our rejoicing into jokes as if struggle against evil is a laughing matter, or reduce the real struggle to merely a meme for the moment or let the established order define it and offer us favors and funds to cosign its distortions of our lives and struggle. Indeed, we must understand and embrace it as it is, an act of solidarity, collective resistance and rightful self-defense in the context of our ongoing struggle for freedom, justice and shared good in this country and the world.

Quickly moving to reductively translate our collective resistance in solidarity and self-defense and to play down the racial and racist character of the assault, the established order media has designated it a “brawl” and the D.A. and FBI would not classify it as a hate crime. But calling the assault a brawl conflates self-defense against an attack with the attack itself, attempts a moral equation of self-defense and assault and thus, reveals again a racialized conception of the just and the ethical which favors the White attackers and oppressor.

It is a fundamental teaching and text of Kawaida philosophy that one of the greatest powers in the world is the power to define reality. This power can be used and pursued for good or evil. If we do it for ourselves in rightful and righteous ways, it means deepening our capacity to understand, engage and change ourselves, society and the world for the best.

But if it’s used by the oppressor, it’s always to achieve and sustain domination, deprivation and degradation of others different and vulnerable. It is indeed the evil power of being able to define reality and make others accept it even when it’s to their disadvantage and contributive to their continued oppression.

Also, as Black people explained in Black social media in various ways, it was not only rightful collective resistance to a clear unprovoked attack, but also an uplifting experience to see Black people coming together to help another Black person unjustly attacked. Likewise, it was uplifting to Black people to see other Black people not ignoring injustice or refusing to get involved, but confronting a collective evil with the righteous anger and rightful collective resistance called for and required.

This is significant, not only in the act of collective resistance in self-defense itself, but also because of what it can mean for the struggle in terms of a consciousness and a commitment to not be passive bystanders at sites of injustice, not walking or running away from the reality of oppression, but confronting it in the various ways it comes and seeks to impose itself, whether it means walking, running or even swimming to the site of engagement. As Nana Robert and Nana Mabel Williams contended, you have to be able to say to both to the “local racist bigots” and the established order “just this far and no further.”

Indeed, as the honored ancestors teach, we are never to turn a blind eye to injustice or a deaf ear to truth. On the contrary, we must bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place among those who have no voice, those different and vulnerable, those suffering, silenced and oppressed.

Moreover, they teach and tell us, we must struggle against those who struggle against us and make a just peace with those who make a just peace with us. For as the Husia says, “Exceedingly good is the presence of peace and there is no blame in peace for those who practice it.”

This act of collective resistance in self-defense has produced a collection of social media memes, replays, video reenactments, community conversations and songs. And again, it is important that this is related to and rooted in the overall struggle for freedom, justice and security of person and people in this country and the world. This is why Nana Sekou Toure warns against creating and claiming struggle songs outside of the revolutionary struggle itself.

Thus, he says, if you truly want to write a struggle song, a really revolutionary song, “you must make the revolution with the people and the songs will come by themselves and of themselves”. The challenge, then, is to intensify and expand the struggle beyond social media and the waterfront to the system itself, its structures, policies and socially sanctioned practices rooted in racism and various other forms and pathologies of oppression.

As might be expected, some questions have been raised of how Black people can celebrate or rejoice over what can be seen as violence from a certain perspective. But it is not celebration of violence as intentional and aggressive use of force to injure or kill. It was a celebration of solidarity and collective resistance in self-defense, indeed, a rejoicing over a small but significant victory over aggressive racist violence imposed on our people for centuries in official and vigilante forms.

Also, such selective performative moral concern about the ethics of self-defense by Black people while claiming, proclaiming and legalizing it for Whites has the rank and repulsive odor of hypocrisy. And the stench becomes thicker when we consider that this country celebrates its many wars in literatures, songs, cinema and official ceremonies, and funds and defends brutal occupations of its own and of its allies as well as armies, special forces and police departments who don’t simply serve and protect.

As we explore signs of possibilities in the way forward, we are reminded of how Nana Dr. Martin Luther King characterized our struggle for freedom, justice and good in the world as a “bitter-but-beautiful-struggle.” It is bitter because it is about savage oppression and sustained undeserved suffering, disablement and death.

But it is also beautiful in that it is about and by a people righteously and relentlessly striving and struggling to be themselves, to free themselves and bring good in the world; a people refusing to be dispirited or defeated, a people resilient, resourceful, soulful, and profoundly secure and sufficient in their own humanity and sense of the sacred within themselves.

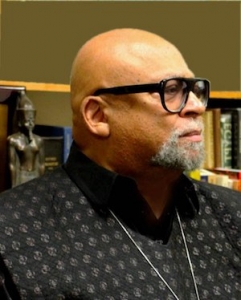

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.