The current and increasing embrace and touting of artificial intelligence was preceded and made possible by the earlier progressive production of the artificiality of life, that is to say, the undermining and diminishing of what it means to be human and natural in all its complexities.

It is reflected in the ways too many in this society relate negatively to other human beings and to the natural world, how pets are often more prized, protected and provided for than fellow human beings; how the internet has interrupted, altered and digitized our relations and ways of relating with each other; and how small-minded and cold-hearted self-referentiality, focusing on oneself as the only meaningful self in the world, has become the central reality of so many.

Thus, the central concerns about the threats of artificial intelligence must be joined with the unavoidable question of the existing and ongoing artificiality of human life that invites and welcomes its counterparts, not only artificial intelligence but also artificial feelings and ultimately, artificial conceptions of human relations, human beings, and the natural world.

Now, it is a fundamental Kawaida contention that the hub and hinge on which the whole of human life turns are human relations. We come into being in relationship and either fail, flounder, or flourish because of them. Thus, quality relations are key to grounding, development and flourishing and to being and becoming fully human. To talk of and strive to be and become fully human does not mean we are not already human, but rather suggests an expanded and expansive effort to realize fully our human potential, i.e., come into the fullness of our African and human selves.

Thus, central to this question is how do we, as Haji Malcolm urged us, protect, and promote our humanity, and how do we cultivate and develop it in the most fruitful and fulfilling ways and thus come into the fullness of ourselves? For we are not only submerged in worshipful, disabling, and dependent relations with technology, logging on constantly and living and sleeping with our devices, we have also begun to see it as a paradisical path to a new anti-human form of self and reality.

For stripped of all its mystification, scientism, and consumerist advertising, it is a self and reality shaped by machines and devices, derivative, dependence-creating and thus agency-reductive. And the pandemic only heightened our sense of isolation, alienation and device-dependency.

But as so many have discovered, there is no magic balm in machine-occupied Gilead, and studies constantly reveal a rising and expanded tide of alienation, anxiety, depression, and device-dependency, especially among the young. For our lives become mediated and made real and relevant by machines and our relations with them, leaving less, often little and sometimes no time to listen to, hear and act with and for those of great meaning and importance to us for countless human reasons.

What is missing, then, in this rushed reveling in the imagined new world of technological wonders is rightful and adequate concern with the human and relational reality in which the concept and practice of being and becoming expansively human is rooted and realized.

Here, I want to pose the ancient Egyptian Kawaida-Maatian concept of the sedjemic person, sdmw as an essential way out of this maze and iceland of machine orientations and inducements. Although its root word, sdm, is translated variously as listening, hearing and obeying, I want to advance a more expansive meaning of the word, engaging it as a person for whom rightful attentiveness, empathetic understanding, and appropriate action as requested or required are essential principles and practices for achieving what it means to be and become truly human and come into the fullness of ourselves.

Each of these three essential elements carries with it a specific kind of responsiveness linked and interrelated to the other, forming an organic integrated whole. These elements of responsiveness are both principles and practices, moral values that elicit and require a moral practice. Listening calls for rightful attentiveness; hearing calls for an empathetic understanding; and obeying or rather complying requires appropriate action in response.

This responsiveness is to the Divine, others and the world. And the ground and linking concept and practice for this responsiveness is Maat, the principle and practice of rightfulness of and for the Divine and in and for ourselves, others and the world.

Being a sedjemic or morally responsive person, then, is rooted in responding first to the moral sensitivities, obligations and actions required by Maat which is goodness and rightfulness. Thus, Intef, son of Sent, in defining his moral practices in relations with others, says “I am a sedjemic person, one who listens to Maat and ponders it in his heart.” The verb sedjem here not only means listen, as indicated above, but also one who listens and hears, and ultimately acts according to what is requested and required.

Intef says, he ponders Maat in his heart, suggesting he thinks deeply about how to live a Maatian life, be a Maatian leader and relate rightfully to his fellow human beings. Thus, he also writes that he is “generous to the poor and needy; one who does what is beneficial to his fellow human beings; a source of knowledge for those who don’t know and one who teaches a person what is useful to him; and one who is “skilled in speech in situations of the narrow mind and the constricted heart.”

Thus, being and becoming truly human is a morally sensitive and thoughtful ethical practice. We must listen to each other then, be rightfully attentive to each other in our speaking and in our silence, for if we listen caringly and considerately, we can even hear each other’s silence actually speak to us in beautiful, needful and some of the most meaningful ways.

To hear in this Kawaida-Maatian and African sense is to feel for and feel with, in a word, to have and practice an empathetic understanding. It is a sharing of hope and hardship, suffering and satisfaction and of life, work and struggle. And finally, the sedjemic person who is rightfully attentive, and has empathetic understanding must and does act appropriately as requested or as the situation required. For as always, practice proves and makes possible everything.

One of the most definitive moral self-presentations from ancient Egypt of the sedjemic person is that of Intef, son of Sitamun. He says, “I am a beloved servant; one who speaks truth and does not pass over his faults; disciplined in heart and mind in times of haste; confident in doing things in the midst of the people; one who does more than what is asked of him; one whose insightfulness is applied in every matter; one who hears and acts as asked; one who performs efficiently as desired; an attentive hearer and a determined doer; thoughtful and eloquent; cool-headed, free from haste; a Maatian person free from irreverence; one sensitive to pain and suffering; and a man of integrity, upright and effective in action.”

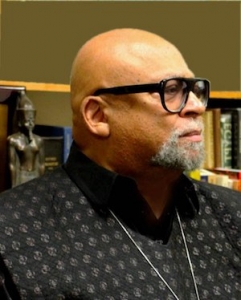

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.