The Los Angeles Police Commission approved an updated department policy to comply with Senate Bill 98, which exempts media professionals from having to comply with police dispersal orders while covering protests, marches and other types of demonstrations.

The legislation states that “law enforcement shall not intentionally assault, interfere with, or obstruct journalists” covering protest demonstrations and other civic actions. It also bars officers from citing journalists for failure to disperse, and bars officers from violating or interfering if journalists are solely gathering, receiving or processing information.

The updated also policy broadens the department’s definition of media to include freelance reporters and students reporting for their high school or college newspapers.

“But, should a member of the media — either the most well-recognized or freelance — do things that violate other laws other than those discussed in the statute, then the department may take action because being a member of the media does not give you immunity from engaging in destructive acts or other acts,” said Liz Rhodes, director of the LAPD’s Office of Constitutional Policing.

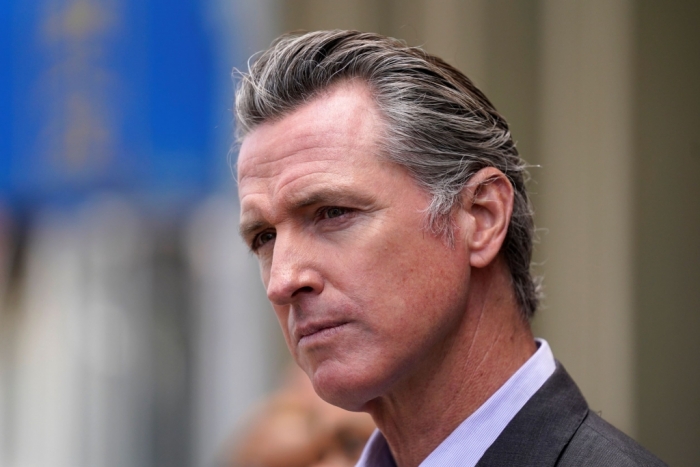

Southland journalists celebrated on Oct. 9, when the bill was signed into law by Gov. Gavin Newsom.

“Media organizations have documented more than 50 incidents of journalists being injured, detained or arrested over a 12-month period,” the Greater Los Angeles chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists said in a statement on Oct. 9.

“SPJ/LA viewed SB 98 as a necessary step to safeguard coverage of demonstrations by ensuring that journalists may continue reporting in an area after an unlawful assembly has been declared.”

SPJ worked with a coalition of more than 20 other journalism organizations, media unions and advocacy groups and “spent months informing state legislators” of the urgent need to “safeguard press freedoms in California.”

The coalition contended that the Los Angeles Police Department’s “use of unlawful-assembly orders has expanded dramatically with little oversight,” especially in the months since George Floyd was killed by police in Minneapolis on May 25, 2020, drawing thousands into the streets to protest.

“Our chapter has been frustrated by the number of incidents where police have arrested, detained, or manhandled journalists who were simply attempting to do their jobs,” Ashanti Blaize-Hopkins, SPJ/LA vice president, said in October. “We decided earlier this year that we needed to join forces

with other journalism groups to demand substantive change — by seeking legislation that will hopefully prevent such incidents from happening in the future.”

The bill was opposed by the California Police Chiefs Association and other law enforcement groups, who supported a last-minute effort to add an amendment requiring journalists to seek the permission of a police commander before entering closed areas around protests. The amendment was eventually dropped.

The Los Angeles Police Department’s treatment of journalists has come under fire over the last year, particularly following its detention of journalists — including the Los Angeles Times’ James Queally and Spectrum News 1’s Kate Cagle — during March demonstrations in Echo Park.

On April 21, the ACLU of Southern California warned the LAPD and other agencies in the region that it will closely monitor how law enforcement treats journalists at protests.

That warning came a day after a coalition of journalism groups sent a letter to Los Angeles law enforcement agencies and government leaders demanding that media be given appropriate access to cover public protests and not be arrested while working in areas where dispersal orders have been issued.