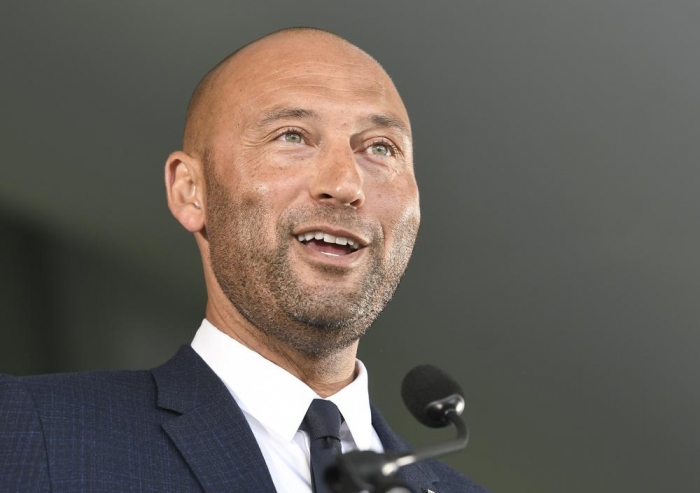

Derek Jeter was simply Derek Jeter on his special day — smooth as silk.

On a Wednesday afternoon that turned cloudy with the temperature in the 70s and a few sprinkles in the air and adoring fans chanting his name, the former New York Yankees star shortstop and captain was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame after a long wait necessitated by the pandemic.

Greeted by raucous cheers in a crowd estimated at 20,000 that included NBA luminaries Michael Jordan and Patrick Ewing, several of his former teammates, and Hall of Fame Yankees manager Joe Torre on the stage behind him, Jeter took his turn after fellow inductees from the class of 2020 Ted Simmons, Larry Walker and the late Marvin Miller were honored. Jeter was touched by the moment and acknowledged how different the ceremony seemed in the wake of the recent deaths of 10 Hall of Famers.

“I’m so honored to be inducted with you guys and linked to you forever,” he said. “The Hall of Fame is special because of those who are in it. We’ve lost way too many Hall of Famers over the last 20 months. These are all Hall of Famers who would have or could have been here, so for that reason it’s not the same.”

What was the same was the adoration displayed by the fans, who always marveled at his consistency.

“I had one goal in my career, and that was to win more than everyone else, and we did that, which brings me to the Yankee fans,” Jeter said as the fans erupted again. “Without question, you helped me get here today as much as any individual I’ve mentioned.”

He gave much of the credit to his parents, who were in the audience with Jeter’s wife, Hannah, and their two young daughters.

“Mom, you taught me any dream is attainable as long as you work harder than everyone else. You drilled that in my head over and over and over and you led me to believe it,” Jeter said. “You told me never to make excuses, you wouldn’t allow me to use the word can’t. Dad, you’ve been the voice of reason. You taught me to be patient, to listen and think before I speak. You’ve always been there for advice and to this day you’re the first person I go to. I know when I retired you said you played every game with me and I know you recall from time to time telling me, ‘You keep building that resume.’ Look where it’s gotten us today.”

The ceremony was delayed a year because of the coronavirus pandemic and it didn’t matter much to Walker, the second Canadian elected to the Hall of Fame. He gave up hockey when he was 16 to focus on baseball. He was selected in his 10th and final year on the writers’ ballot after a stellar career with Montreal, Colorado and St. Louis that included 383 homers and three batting titles.

“It’s taken a little longer to reach this day (but) for all your support I’ve received throughout the years from my home country, I share this honor with every Canadian,” said Walker, who retired in 2005. “I hope that all you Canadian kids out there that have dreams of playing in the big leagues, that see me here today gives you another reason to go after those dreams. To my adopted home, the United States, I thank you for allowing this Canadian kid to come into your country to live and play your great pastime. I think we’re all pretty fortunate to have two amazing countries side by side.”

The 72-year-old Simmons, who starred in a 21-year career with the St. Louis Cardinals, Milwaukee and Atlanta, punctuated his speech to thank four pioneers of free agency — Curt Flood, Catfish Hunter, Andy Messersmith and Marvin Miller — “who changed the lives of every player on this stage today by pushing the boundaries of player rights.”

“Marvin Miller made so much possible for every major league player from my era to the present and the future,” the former catcher said. “I could not be more proud to enter this great hall with this great man. Even though my path has been on the longer side, I wouldn’t change a thing. However we get here, none of us arrives alone. I’m no exception.”

Miller, who transformed baseball on the labor front by building a strong players union and led the charge for free agency in the mid-1970s, was honored posthumously. Four years before he died at 95 in 2012, Miller respectfully asked to be removed from consideration for the Hall of Fame after being passed over several times.

“One thing a trade union leader learns to do is how to count votes in advance. Whenever I took one look at what I was faced with, it was obvious to me it was not gonna happen,” Miller, head of the Major League Baseball Players Association from 1966-83, wrote in 2008. “If considered and elected, I will not appear for the induction if I’m alive. If they proceed to try to do this posthumously, my family is prepared to deal with that.”

The family didn’t. Instead, Don Fehr, who was hired by Miller to be the union’s general counsel in 1977 and succeeded him eight years later, had the honor.

“Of all the players I had the privilege to represent, I want to thank you Marvin,” said Fehr, now the head of the National Hockey League Players Association. “Baseball was not the same after your tenure as it was before. It was and is much better for everyone. You brought out the best of us and you did us proud.”

The virus forced the Hall of Fame to cancel last year’s ceremony and this year’s was moved from its customary slot on a Sunday in late July to a midweek date.