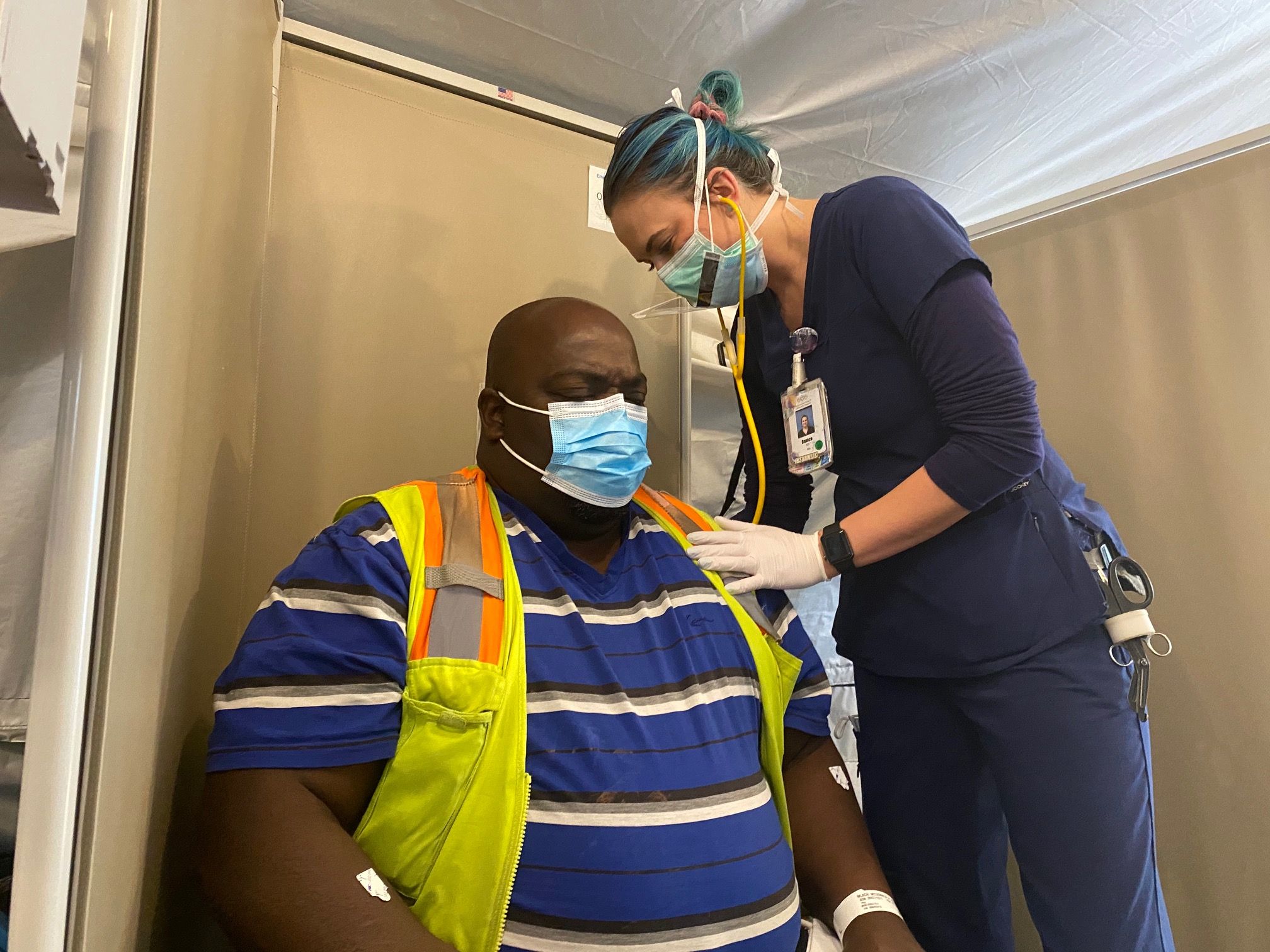

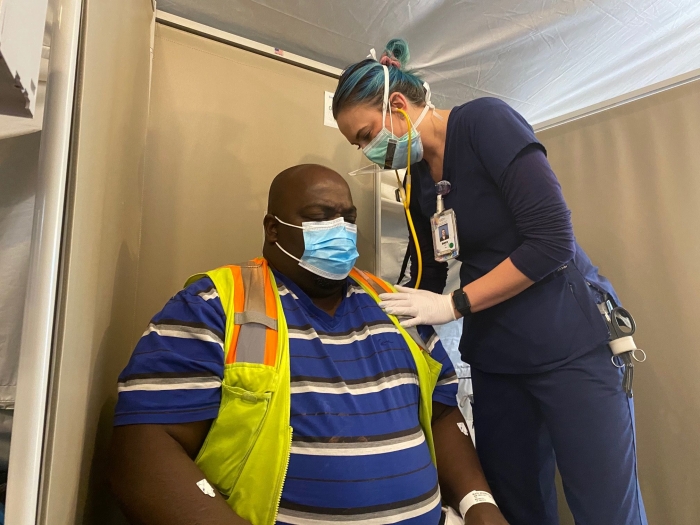

Inside a military-style MASH tent, a nurse with aqua blue hair and a mask across her face touches the arm of her patient, sitting heavily upon a folding chair.

This is Danica Riedlinger, at very front lines in the fight against COVID-19, putting her life on the line for a cause and community she believes in.

“I feel like it’s part of who I am to step up and do my part for the community,” said Riedlinger, 32, an Emergency Department nurse at the Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital (MLKCH). “Part of why I became a nurse is to be involved in caring for people during events like this.”

Events like these—but there haven’t been events like this. Not this big. Not this complex.

It makes what Riedlinger is doing—and hundreds of other front-line MLKCH staff—even more extraordinary. Hundreds of doctors and nurses in the United States have been sickened, some critically, by the virus. Supplies of basic protective equipment—masks, gloves, robes—are in short supply across California and the nation.

MLKCH staff know they are putting their lives on the line. And they are still here.

Riedlinger is working the triage tent erected outside the hospital’s busy Emergency Department. The tent is there exclusively to keep patients suspected of COVID-19 separate from other patients.

Perry Lee McDonald, 49, is one of them. The warehouse worker from Watts is having chest pain and difficulty breathing. His temperature is 101.

It could be his chronic high blood pressure. But McDonald isn’t taking any chances. “I unload trucks and do quality control,” he said. “Everything I touch comes from China.”

China is, of course, the place COVID-19 started. It has since spread to almost every country in the world, sickening hundreds of thousands and killing nearly 8,000 people.

The question is not if the virus will spread to MLKCH’s service area of South LA. It’s when.

South LA is particularly vulnerable. People in this low-income community can’t necessarily shelter in place. Many are homeless. Many are ill—this is one of the most-medically underserved areas in the nation.

On the hospital’s second floor, in the command center established more than a week ago, key staff from MLKCH’s leadership team are wrestling with difficult issues. Although the hospital currently has enough supplies, the team here knows that could change quickly.

“We need goggles, N-95s, surgical masks, pretty much every kind of personal protective equipment,” said Debra Flores, chief operations officer for the hospital and the lead for this emergency response. “What aren’t we thinking of? What more can we do?”

MLKCH’s response team has a leviathan task: finding critical medical supplies despite a national shortage; planning for an expected surge in infected patients while coping with the hospital’s already high volume; managing the anxiety of staff; and building in round-the-clock redundancy so if any of the MLKCH team gets sick, the show will go on.

Calls have been made to every possible source of supplies—government, private companies. The International Medical Corps, normally an international relief organization for disaster-hit countries elsewhere, is donating tents and supplies. In a stroke of innovation typical of this hospital, staff are calling beauty salons and supply stores in hopes of raiding their stock of face masks and protective gloves. Dime Nail Salon’s Edward Osei-gyimah delivered two bags full of masks and gloves this morning.

Thousands more are needed. The MLKCH ED can easily run through hundreds of surgical masks in one day, and up to 180 or more of the coveted N-95 masks.

“It’s an all-hands on deck, all-ideas welcome effort,” said Debra. “If shortage is the reality, then our job is to figure it out.”

Meanwhile, the hospital is shut down to all but the most urgent-case visitors. Patients who can be sent home are being sent home to make room for the critical COVID-19 cases that will come. Updates and “Know-Do-Shares”—quick, digestible briefings and guidelines sent out to all staff—are produced daily, sometimes more frequently. Doctors and nurses work tirelessly to identify, isolate, and test.

“I do have concerns for my own health,” Riedlinger said as she worked with three patients inside the tent. “Being exposed on a regular basis, being on the front line automatically puts me at risk.”

She is thankful she has no children or elderly family to care for.

“If I contract the virus I’ll be able to quarantine without putting anyone at risk.”

Inside the ED, protocols have been set up to isolate and treat “PUIs”—patients under investigation for COVID-19. Hallways have been cleared and room doors shut so that such patients can be escorted safely without infecting others. Donning and doffing instructions are hung on doors to remind clinical staff how to safely put on and dispose of protective equipment.

“Everyone has really stepped up and shown great teamwork, poise and diligence, and critical thinking,” Riedlinger said. “This is new for all of us. But it has shown that we’re all in this together.”

Gwen Driscoll is the senior director of brand communications at Martin Luther King, Jr. Community Hospital and a former journalist for the LA Times and the Orange County Register