Pro football is discovering that the spirit of the Rooney Rule is being violated.

NFL Commissioner Roger Goodell made that a point of emphasis in his state of the league speech during Super Bowl week. So count on Goodell finding ways to more strongly implement the policy that requires teams to interview minority candidates for coaching and executive positions.

Those interviews still have been taking place, but, to use a word that has taken on highly negative connotations but often is applied nowadays, are they simply tokenism?

Goodell recognized that could be true when he said in January:

“Clearly, we are not where we want to be on this level. We have a lot of work that’s gone into not only the Rooney Rule but our policies overall. It’s clear we need to change and do something different.”

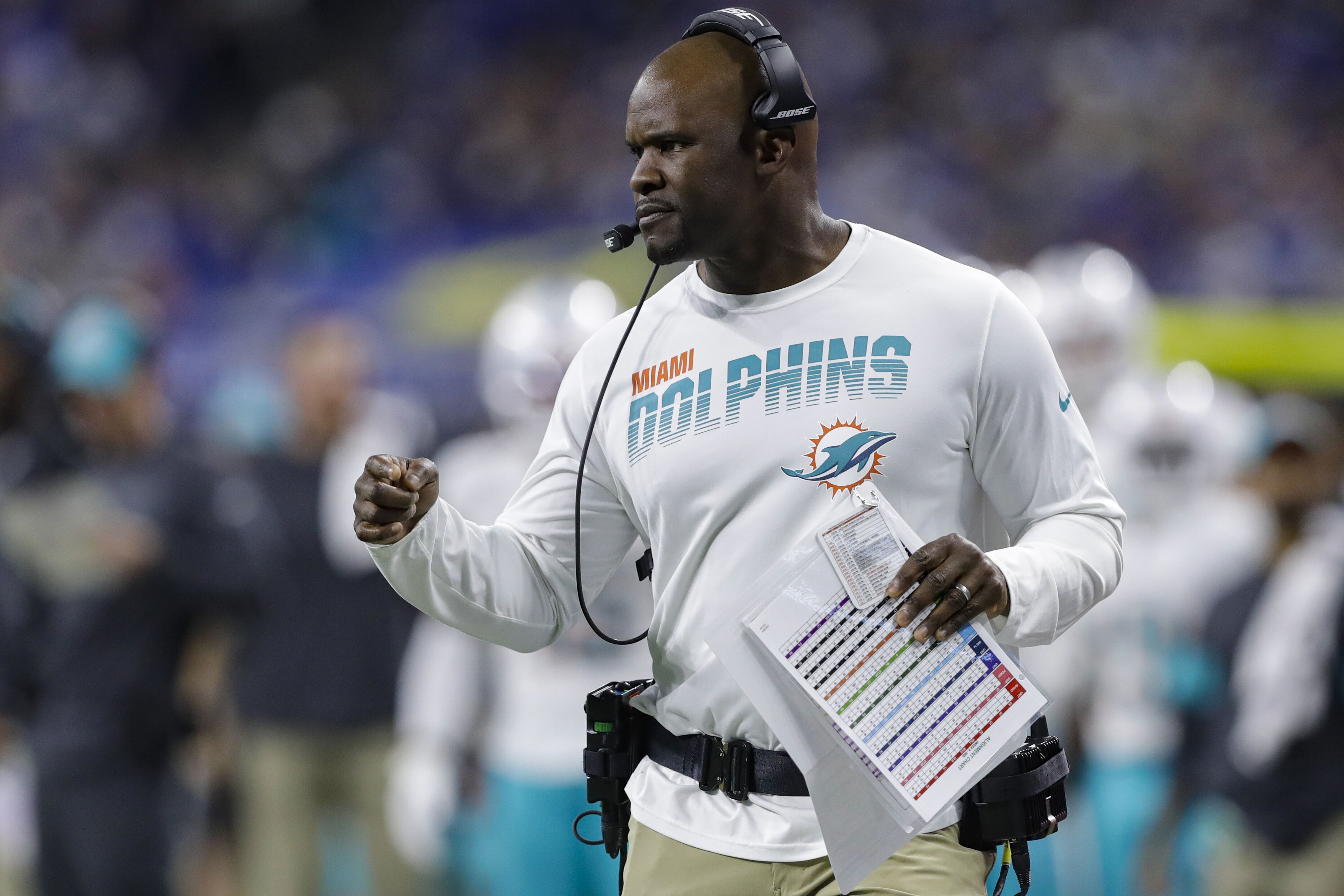

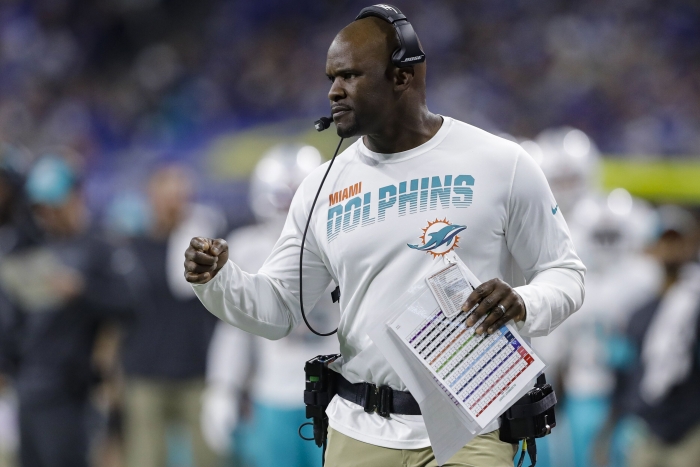

Noting how few minorities are in coaching and general manager jobs right now _ the only head coaches are Ron Rivera, Anthony Lynn, Mike Tomlin and Brian Flores, and the GMs are Chris Grier and Andrew Berry _ Goodell said:

“There’s no reason to expect we’re going to have a different outcome next year without those kinds of changes and we’ve already begun engaging in those changes. Not just with our diversity committee, not just with the Fritz Pollard Alliance, but others. And trying to figure out what steps we could take next that would lead to better outcomes.”

Adds Troy Vincent, who oversees football operations for the league and is African American:

“Every club must have a diversity action plan _ at the league and across the clubs, it must be an industry standard. Development of the talent pool, which we continue to do that at the commissioner’s office. There is a strong pipeline there. And there must be the education of the (executive) suite to bring more familiarity and to foster trust.”

Two of the people Goodell and Vincent are likely to listen to are Hall of Fame coach Tony Dungy, and Steelers owner Art Rooney II, whose father, Dan, championed the Rooney Rule.

Dungy might be the most influential coach in NFL history when it comes to off-field issues. He’s been an adviser to Goodell and others at the league for years _ even while still coaching the Colts. His voice is an important one, as is his view of the Rooney Rule’s application in recent years.

“What I think has happened is people have said, ‘Let me interview a minority candidate to satisfy the rule, and then I can get on with this hiring process or hire who I want to,’ ” Dungy says. “The whole point of the rule was to slow down the process, take your time, get the best candidate and make a decision. But there’s so much pressure now on all of them to do it quickly, get the ‘No. 1 candidate,’ put together a staff. Nobody wants to take their time. That is the major problem.”

Dungy and Vincent believe such expedience ignores that there is a deep pool of accomplished candidates. Teams aren’t diving into it.

“I get a little perturbed when people say we got to put more people in the pipeline, that there are not enough people of color,” Dungy says. “I just don’t see that. There are a lot of good people.”

Vincent echoes such thoughts, with several caveats.

“I just think awareness of candidates,” he says. “Immediately I go to barriers of mobility. There’s a double standard, which sometimes is not discussed. We are examining now the coaching legacy and number of coaches who now coaching with sons and sons-in-law and brothers/siblings. Those become barriers to entry.

“We also have to look at, are there prohibitors in contracts where coaches being blocked due to language in their contracts?

“It is very difficult for men of color to progress. They are not even in the house, in the pool, because of barriers of mobility.”

Art Rooney cautions that there aren’t likely any magical fixes that will immediately improve adherence to the spirit of the rule. He believes looking at history and how the rule has worked in the past can be a helpful tool.

“I don’t think we can fix everything in one meeting or even one year,” Rooney explains. “It’s an ongoing process and I don’t think there is any silver bullet that if we do one thing, we are going to resolve the situation. There should be some things that can be done in the short term, but in terms of developing the pipeline further on coaching and executive positions, that would take a longer period of time.

“The first thing we are going to do is talk to people who have been involved in the process and understand what the thinking was. Talk to people who were interviewed, assess where we are and then start to talk to people about ideas on what we can do to improve the situation.

“There have been ideas about attempting to have people slow down the process and just make certain people in the pipeline are getting the attention they should be getting. I would agree there are a lot of good candidates out there, people who should be getting interviews and that doesn’t seem to be happening.”

Vincent has a checklist of items to be addressed as soon as possible.

“An intentional training, awareness, and communications plan should be implemented,” he says. “In addition, we must encourage a safe nonjudgmental educational environment that seeks to provide a clear understanding of the ‘why’ behind hiring biases. These things coupled with football and (executive) suite personnel operating under the notion that diversity is good for business, will ultimately provide an opportunity to build the business case for diversity in hiring.

“We must truly examine short term, intermediate, and we’ve got to have some long-term goals for our business to thrive. Diversity is good business, inclusion is a choice.”