A court ruling this week puts the police murder case of former Black Panther Mumia Abu-Jamal back in the spotlight years after it drew the attention of Amnesty International, Hollywood celebrities and death penalty opponents worldwide.

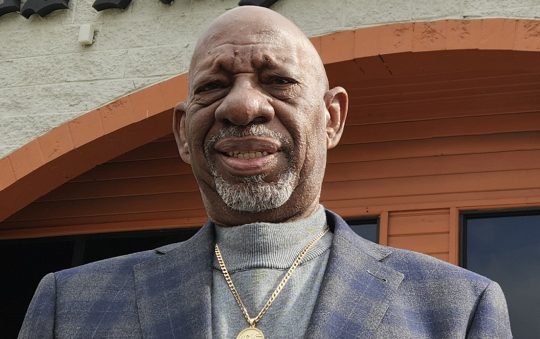

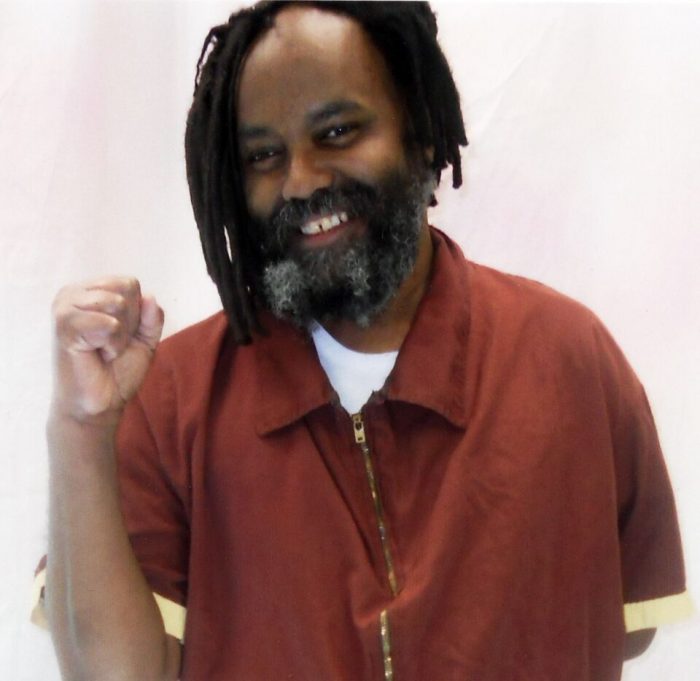

Abu-Jamal, a one-time taxi driver and radio reporter, emerged over four decades in prison as a vocal critic of the American justice system, especially the racial bias he saw at the heart of his 1982 trial.

His writings and commentaries from prison, including the 1996 book “Live from Death Row,” have earned him acclaim from progressive scholars and activists _ along with the disdain of police unions, conservative politicians and the widow of Daniel Faulkner, the young patrolman slain in downtown Philadelphia on Dec. 9, 1981.

“Thirty-eight years!” Maureen Faulkner cried out in court this fall during the latest post-trial arguments, leading city Judge Leon Tucker to have her escorted out. “This is wrong!”

Tucker’s ruling Thursday may prolong her agony, but follows a 2016 U.S. Supreme Court finding that former Pennsylvania Chief Justice Ronald Castille had been wrong to hear a death-penalty appeal that had come through his office when he was Philadelphia’s district attorney from 1986-1991. Castille had done the same in Abu-Jamal’s case.

“They shouldn’t have been able to raise the issue about me, because they never asked me to recuse myself,’ Castille, now retired, told The Associated Press on Friday. “The court … knew I’d signed off on the appeal, but I had nothing to do with the trial.”

Tucker, in a 37-page opinion, said the appearance of bias was clear and that Abu-Jamal’s appeal should be reargued by the current state Supreme Court based on the briefs his lawyers filed at the time.

“The slightest appearance of bias or lack of impartiality undermines the entire judiciary,” Tucker wrote.

District Attorney Larry Krasner, a civil rights lawyer intent on criminal justice reform who took office this year, has not decided whether to challenge the ruling.

The jury convicted Abu-Jamal of killing Faulkner, 25, after he pulled over Abu-Jamal’s brother in an overnight traffic stop. Prosecutors called the evidence against him overwhelming, and said he was shot by Faulkner during the exchange of gunfire.

He spent nearly three decades on death row before a U.S. appeals court threw out the death sentence over flawed jury instructions in 2008, after a hearing that attracted hundreds of chanting supporters. Prosecutors dropped their bid to restore the death sentence, leaving Abu-Jamal to serve a sentence of life without parole. The buzz around his case largely died down, and his appeals hit a dead end in 2012.

But his closest supporters remained energized.

“We had hope that something would come along, and lo and behold it was the Williams case,” said Pam Africa, 73, a leading organizer for Abu-Jamal supporters, referring to the 2016 Supreme Court case involving Castille.

Officials with the city’s Fraternal Order of Police did not immediately return a message seeking comment Friday, but they have been steadfast in their support of Maureen Faulkner and the verdict over the years.

Civil rights lawyer David Rudovsky, who worked on an early Abu-Jamal appeal, said the case has raised many of the fairness questions that still plague the nation’s courts, including the racial makeup of juries and the racial breakdown of people on death row.

“The race bias, the judicial bias, the questions of identification and prosecutorial commentary or misconduct, we’re still struggling with them,” said Rudovsky, a University of Pennsylvania law professor.

“And, of course, with the killing of an officer, and a Black activist (charged), it was a recipe for all of the conflicts that we see, then and now.”