We should all be appalled—but not surprised—to learn that young black students are once again being targeted for unequal treatment at the hands of charter school officials—this time Mystic Valley Regional Charter School in Malden, Mass., is the culprit but they are hardly alone in the offensive against black girls’ hair. The recent flurry of attention to this case, in which the school has forced detention and barred activities for girls because they wear braids with hair extensions, instantly brings back bad memories of similar incidents.

Remember when seven-year-old Tiana Parker was sent home from a charter school in Tulsa, Oklahoma, for wearing dreadlocks? The school rules said they are a fad. (This fad dates as far back as 2500 B.C.) How about five-year-old Jalyn Broussard who was forced to change his fade haircut because his Belmont, Calif., Catholic school said it was a distraction? Twelve-year-old Vanessa VanDyke was given a week to cut her natural hair or be expelled from her private religious school because it too was a distraction. A Buras, La., Rastafari student missed 10 days of school before submitting to pressure that he cut his dreadlocks because they violated a rule on the length of boys’ hair. A Lorian, Ohio, charter school recently tried and failed to explicitly ban “Afro-puffs and small twisted braids.”

These practices and policies have no place in our educational institutions.

Misguided administrative attempts to overpolice black and brown bodies result in children of color experiencing school in radically different ways than their peers. The paltry excuse put forward by the school’s leadership that hair extensions highlights inequities is utterly ridiculous and is emblematic of irresponsible and uninformed educational leaders. So is the notion that wearing one’s hair the way it grows out of many people’s head is a distraction. At a basic level, one’s hair has very little, if anything at all, to do with a child’s educational development. We need look no further than political activist and retired university professor Angela Davis, actress Amandla Stenberg, Nobel Laureate Toni Morrison, Grammy winner Lauryn Hill, filmmaker Ava DuVernay, professor and news show host Melissa Harris-Perry, or Ashley Allison, a former White House director in the Office of Public Engagement.

Education should never attempt to stamp out culture but expand student’s exposure to various people and experiences. Thank goodness, for the school and their other students, that these Malden girls spoke up in the midst of being treated unfairly because of their hair.

The socio-emotional and school penalties these young women have faced is far too severe. Research by a Schott Foundation grantee at the Center for Civil Rights Remedies found that black students in Massachusetts are missing inordinate days of instruction due to suspensions over minor issues. This is also true across the country. These kinds of disciplinary measures put students on the fast track to failure: poor achievement, lower graduation rates and inevitably in the claws of the school-to-prison pipeline. The girls don’t deserve punishment. A report by the National Black Women’s Justice Institute, another Schott grantee, highlights that girls of color are being systematically pushed out, and that naturally occurring features are being characterized as unruly and unkempt. It’s time for the assault on black girls to stop.

Hair doesn’t represent an existential threat to order in the school house. Many black mothers, including my wife, will tell you that braids are a style of convenience. They keep their children’s hair neat and styled for weeks at a time so they and their children can spend their time on more important things than daily styling. It’s also a quintessential part of black culture, and shouldn’t be stripped away to make others comfortable. We should keep our hands out of kids’ hair and continue to broaden their minds.

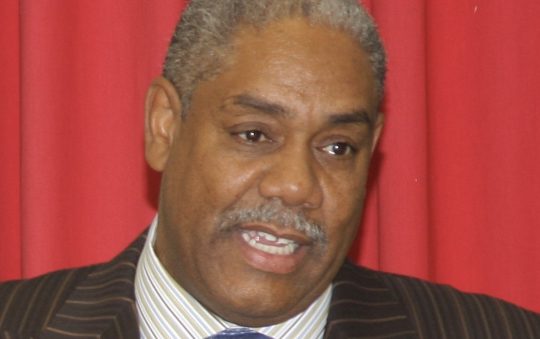

Dr. John H. Jackson is the President and CEO of The Schott Foundation for Public Education in Cambridge, Massachusetts.