This past weekend, the Mississippi Legislature approved the removal of the Confederate battle emblem from the state flag. It’s a sign of the times, historians say, that speaks to the turning spirit of the nation – even happening in a state that has remained a proud stronghold, clinging to enduring customs that nod to a romanticized version of the “Old South.”

Gov. Tate Reeves said he will sign the bill into law.

The deep south state was the lone holdout flying a flag that flaunts the Confederate “Stars and Bars,” which has long stood as a symbol of White supremacy, racism, and slavery. Now, Magnolia State lawmakers say they will create a commission that will design a new flag.

Worldwide protests against injustice and racism have led to a revolt in the United States against monuments that honor public institutions or figures who stood for — or upheld — racism. The death of George Floyd, an unarmed Black man police officers killed in Minneapolis has brought police brutality, racism, and economic inequality in America into sharp focus. That has prompted the nation to look inward and soul search, which has now expanded to questioning the country’s tradition of celebrating controversial figures that honor its racist past.

Across the United States, protesters have defaced, torn down or petitioned the removal of enshrinements honoring confederate soldiers, segregationists, slave traders, white supremacists and others identified as racist.

“There is no room in the hallowed halls of Congress or in any place of honor for memorializing men who embody the violent bigotry and grotesque racism of the Confederacy,” said Nancy Pelosi (D-CA-12), Speaker of the U.S. House of Representatives. On June 18, Pelosi ordered the removal of four portraits depicting confederate leaders from the nation’s Capitol.

In California, after 137 years, legislators announced the removal of statues depicting Christopher Columbus and Queen Isabella of Spain from the Capitol Rotunda. They had been on display under the building’s dome since 1883.

“As the first California Native American elected to the Legislature, I welcome removal of the statue. It is a symbol of genocide and atrocities toward Indigenous people throughout the world, including the United States,” said Assemblymember James C. Ramos (D-Highland), reflecting on the removal of the Columbus monument. “We need to harness this opportunity to portray factual history from the view of those who suffered. Yet, we must also focus on the present in order to change the future.”

These acts around the country have sparked a debate about whether or not history — and public memorialization of our past — should be sanitized.

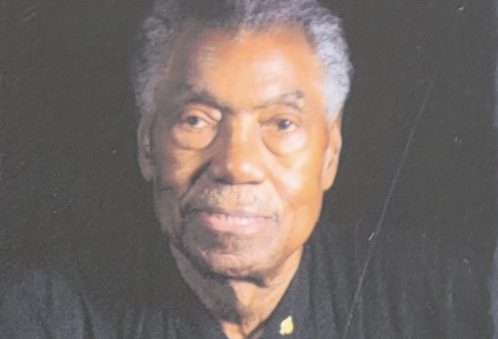

Dr. Daniel Walker, an African American historian and professor, says not creating, funding or publicly displaying these symbols do not equate to “sanitizing” history.

“It is removing what are, in many cases, false history. It is correcting what are misinterpreted histories, and, at some times, removing what is fully oppressive history,” Walker told California Black Media.

Renaming CA State Park Negro Bar, Formerly “Ni**er Bar”

In northern California, a movement to study and correct local symbols deemed racist is brewing around one of the state’s African American-themed landmarks. Negro Bar is an area located within the Folsom Lake State Recreation Area near Sacramento.

Located in the city of Folsom, Negro Bar sits on the west bank of the American River, which flows south into the adjoining Sacramento River.

The picturesque park was named after an area where Black miners once worked during the Gold Rush of the mid-1800s. The miners were isolated because of their color.

At Negro Bar, the Black miners struck gold in 1850, one to two ounces for each man on the average per day, according to an article published in the now-defunct Sacramento Placer Times.

Clarence Caesar, a Black historian at California State Library’s California Historical and Cultural Endowment said Negro Bar is the state’s “first Black gold mining site.”

The park’s name has gone through several changes. It was initially identified as the racial epithet, “(N-word) Bar,” as described in the book “Riches for All: The California Gold Rush and the World.”

Before recent anti-racism protests, local Black community leaders and historians had agreed to continue using the current name, which doesn’t seem to bother the many kayakers, fishers, and hikers of all races that flock to that park during the hottest days.

The Sacramento Chapter of Buffalo Soldiers, a history group that pays homage to the U.S. Army’s Black 10th Cavalry of Company G, staged events at Negro Bar for many years, beginning in the 1990s up until the mid-2000s.

The California Department of Parks and Recreation (CDPR) has stated that it recognizes the seriousness of offensive public symbols and that their interpretations can change over time. The department welcomes feedback from the public.

“In response to comments received in 2018, the department has undertaken a review to better understand the public’s perspective about the name and its continued use,” CDPR stated on its website.

People who are not happy with the current name say Negro is an archaic term for Black people. A petition to rename Negro Bar currently has more than 60,000 signatures.

But some Black people are in favor of staying with the current name. One of them is Jonathan Burgess, a native of Sacramento. His great-grandfather was an enslaved Black man whose owner brought him to California during the Gold Rush.

He says the current name is “part of history.”

He said changing the name would be a “miscarriage of justice” and he doesn’t consider Negro Bar offensive.

He added that some activists don’t have a great understanding of history, and that’s why they want to tear down all monuments.

However, Burgess is firmly against statues that honor Confederate officers. He said those statues lionize people who fought against their own country to maintain slavery.

“These were people who fought against our government,” he said. “Pull them down.”

The city of Folsom and the California State Parks’ Office of Historic Preservation have procured another African American landmark called Negro Hill.

Negro Hill, listed No. 570 in California Historical Landmarks Program, was an established community for African American, White, Asian, Spanish, and Portuguese miners founded by a Black man named “Kelsey.”

Negro Hill, comprising of “Little Negro Hill” and “Big Negro Hill” camps, was located across the South Fork of the American River from Mormon Island, according to Sierra Nevada Geotourism. It was first mined in 1848, four miles from Negro Bar.

Negro Hill had a population of 1,200 by 1853. When laws were enacted to limit the rights of Black people in the 1850s, disenfranchisement forced the African Americans to leave Negro Hill.

What’s left of Negro Hill is now at the bottom of Folsom Lake, swallowed by an expanding lake basin. But the departed buried at the landmark town have been reinterred at the nearby Mormon Island Memorial Cemetery.

Michael Harris, a Sacramento activist who studies both Negro Bar and Negro Hill, ensured that the 36 gravesites received new headstones to keep the Gold Rush era community’s legacy alive.

More Monument Removals Around California

The Statewide Coalition Against Racist Statues (SCARS) and numerous social justice partners celebrated the removal of the Capt. John Sutter statue from Sutter Park in Sacramento.

Sutter, an early settler of California’s capital city, is memorialized as a Gold Rush icon and Sacramento founding father, but, SCARS has stated that he “was actually a cruel and depraved slavemaster.” The removal of the statue, which was issued by the administration of Sutter Hospital, ends “the glorification of Indigenous genocides and ‘De-Sutters’ Sacramento,” SCARS said in a written statement.

“Being a Native American in Sacramento and seeing the idealization of a person who brought a reign of terror to our local Native tribes — and beyond — is triggering. I grew up here, learned about Sutter in my primary school education, participated in the field trips to the fort that left me shocked,” wrote Vanessa Esquivido (Nor Rel Muk Wintu, Hupa, Xicana), an expert on Native American Studies, in a letter to CBM.

In Antelope Valley, an inland area north of Los Angeles, Quartz Valley High School has ditched its Rebel mascot. And Fort Bragg, a small North Coast town with less than 8,000 residents, is considering changing its name. The Confederate general Braxton Bragg, for whom the scenic seaside town is named, enslaved over 100 Black people.

On June 26, President Donald Trump signed an Executive Order to protect monuments, memorials, and statues.

Walker says the solution to preserving history without lifting up racist historical symbols is simple.

“Take all the monuments that have been removed and confiscated, put them in one place,” he said. “Put them in a museum, and say, ‘this is the Confederacy.’ This is how bad we’ve been in America. This is the real story.”