There is, as always, a timeless library of life experiences and life lessons that inform and instruct us on the significance and centrality of this awesome and ongoing sacred narrative and freedom-focused movement forward we know and honor as Black history.

It is in the sankofa instruction to “reach back and retrieve it.” It is found in the ancestral insight that “if you know the beginning well, the end will not trouble you.”

And it is brought into focus and put forth as an ethical obligation in the Kawaida contention that “this is our duty: to know our past and honor it; to engage our present and improve it; and to imagine a whole new future and forge it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.”

Here the past, present and future are linked in a practice and process of continuous development and unfolding. And in studying and analyzing historical patterns and tendencies and understanding their impact and influence on the present, we can open a window and way forward to the future. Thus, Haji Malcolm teaches that “The future belongs to those who prepare for it today.”

Speaking of the critical role of knowledge and education in this preparation, Haji Malcolm also linked this liberating empowerment to our struggle for human rights and the reclaiming and reaffirming of self-respect. It is again knowing the beginning so that the end, the outcome of things, won’t trouble you. Indeed, nothing comes into being by itself. Everything is a result of what came and comes before it. Thus, we must study the past to know the origin and meanings of existing and emerging tendencies and in consideration of our ongoing liberation struggle, the possibilities of freedom and unfreedom, and for building the just and good societies essential to African and human good and the well-being of the world.

To know our past is to know our history by studying it, searching deeply and diligently for its essential meanings and messages, and always its critical lessons of life and struggle. It is to read closely, carefully and continuously its various texts: its oral texts, visual texts (writings, art and other creative expressions of ourselves) and its living practice texts, extracting lessons and understandings about the way our people have lived and live their lives, do their work and wage their struggles, internally and externally for good in the world.

Thus, to know our history is to be aware and grasp that history is not simply a record but a record of a struggle that precedes the recording, and even goes beyond it, for it is ongoing as the present and prelude to the future. Especially for us, history is usefully understood as a struggle and record of a people shaping their world in their own image and interests.

Furthermore, to honor our history is both to regard it with profound respect and to fulfill the intergenerational obligation to learn its lessons; absorb its spirit of possibility; extract and emulate its models of human excellence and achievement; and the practice of the morality of remembrance. Remembrance is central and indispensable here, for it involves remembering and paying rightful homage to our ancestors, the placemakers and waymakers who created space and place for us and opened the way before us.

I speak of the great and small, the extraordinary and ordinary, the known and unknown who dedicated and offered their life and death in our ongoing struggle to be ourselves and to free ourselves and to bring and sustain good in the world. And if we are to honor them rightfully and reciprocally giving what was given, there is no better way to honor them than to try as best we can to emulate them in their excellence, living and advancing the legacy they left us.

In this way, we make ourselves worthy of the love and life they gave us, the sacrifice and service, and the dedicated and disciplined work they did and the righteous and relentless struggle they waged for us and a new and another world of shared and expansive good. What I’m stressing here is that with every principle, program and proclaimed commitment, there must be a practice that proves and makes it possible.

Indeed, as we always say, practice proves and makes possible everything. And the commitment we claim to our ancestry, history and the personal and collective work and struggle to know and honor our history is not exempt from this essential ethical imperative.

At this point, I want to return to the concept and practice of sankofa in this month of heightened remembrance, reflection and homage to our honored ancestors. Now, there are many and multiple ways to understand and explain sankofa, but here I want to interpret it in ways that not only stress the past, but also call forth and aid in cultivating sensibilities, thought and practices that link the past, present and future in creative and fruitful modes of engagement.

As I have noted elsewhere, sankofa is a self-conscious reaching back in the past, in our minds and memory and bringing forth the best of our sensibilities, thought and practice and using them to ground ourselves, orient ourselves and direct our lives toward good and expansive ends. The sankofa symbol is a bird with feet and breast forward and head and neck turned backward and holding an egg in her beak.

A Kawaida reading of this symbol interprets the forwardness of the feet and breast as representing a rootedness in the present and also an orientation toward the future. The head and neck turned backward represents a turning towards the past, and the egg in the beak traditionally represents a kind of treasure trove of goods from the past.

However, the egg can also be understood simultaneously as both a treasure trove from the past which contains the potentiality and promise of the future. For the egg by definition is a source of potential being and a promise of becoming.

Indeed, in Dogon theology and its creation narrative, Amma, God, is conceptualized and discussed as the egg and womb of the world with infinite creative capacity and with the seed of creation at the center of himself. Thus, a holistic conception of the symbol speaks to the unity and interrelatedness of the past, present and future.

And it reaffirms the Kawaida definition of our central duty of knowing and honoring our past, engaging and improving our present, and imagining a whole new future and forging it in the most ethical, effective and expansive ways.

Let me close by noting that the rightful honoring of our ancestors and the great composite legacy of the past they have left us begins and continues with valuing our history as a sacred narrative worthy of the most careful and committed writing, reading, teaching and telling. For as Nana Dr. Mary Mcleod Bethune taught, “We are custodians and heirs of a great legacy” and as we say we must bear the burden, glory and obligations of this history and legacy in good, creative and expansive ways.”

Likewise, Nana Dr. Carter G. Woodson challenged Africans to dare greatness and emulate the deeds of their ancestors, to “build . . . upon the foundation which they have laid,” proving wrong the false and genocidal “prophets who said they would be exterminated, and on the contrary, they enrolled themselves among the great . . . in the service of truth and justice.”

Nana Bethune and Nana Woodson call here for African excellence and moral agency, echoing the Husitic instructions of our ancestors from Kemet who called us to “strive for excellence in all you do” and taught us to remember, in our strivings and struggles for an expansive and inclusive good in the world, that “every day is a donation to eternity and even one hour is a contribution to the future.”

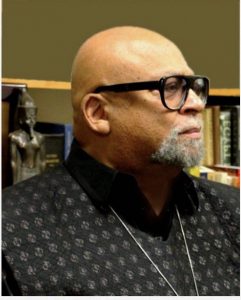

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.