As a former history teacher, I often quote George Santayana’s admonition that, “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it.” But one cannot remember that which one does not know. And that is the case for too many people regarding the Tulsa Race Massacre. And for good reason.

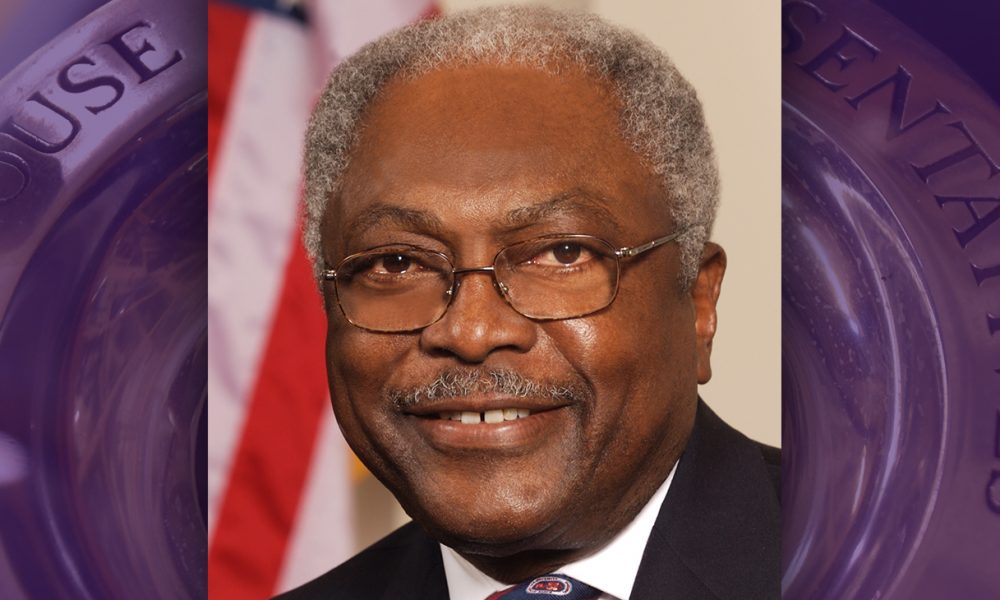

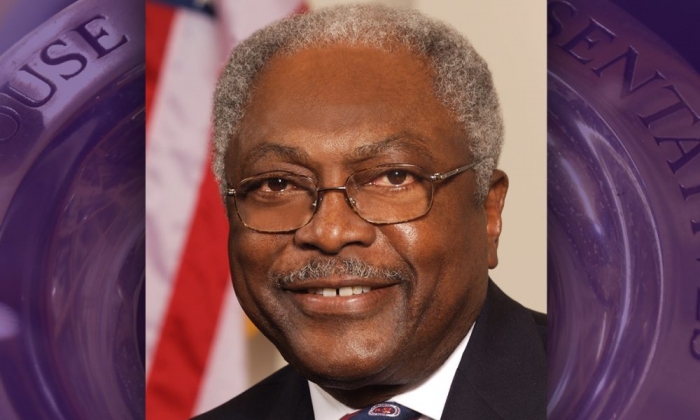

The more interactions I have with folks in Washington and around the country, the more appreciative I am of Ernestine Walker, Marybelle Howe, William Howell, Rosa Harris and many other teachers, and some of the other students they taught, and with whom I studied and debated on the campus of that little HBCU (historically black college and university) – South Carolina State – in Orangeburg, South Carolina.

I was blessed with integral knowledge of Tulsa, Rosewood (Florida), Hamburg (South Carolina) any many other historic – and horrific – events that were “whitewashed” by newspapers and left out of history books. I still remember the one-on-one session I had with Ernestine Walker discussing Tulsa native John Hope Franklin’s outstanding book “From Slavery to Freedom” as a blessed experience. And it was a blessing to have had a one-on-one with John Hope himself when he chaired the “race committee” for President Bill Clinton. I still wonder whatever happened to the product that committee produced. I was also blessed by Tulsa native Alfre Woodard, who wrote the foreword to my memoir, “Blessed Experiences.”

The Tulsa Race Massacre is a prime example of inflaming issues and ignoring history. They both significantly lead to the inability and failure to learn the real lessons that true history can teach us. It was the inflammatory reporting of the chance encounter of a young Black man, Dick Rowland; and a young white elevator operator, Sarah Page, that ignited one of the deadliest episodes of racial violence in our nation’s history.

On May 31st, 1921, the Tulsa Tribune newspaper printed the headline; “Nab Negro for Attacking Girl in Elevator,” and the same edition included a report of a white mob’s plan to lynch Rowland. The newspaper account was based on false claims that Mr. Rowland sexually assaulted Ms. Page, a white woman; and is cited as the spark that incited a mob to burn and loot 35 blocks in the Black Greenwood neighborhood of Tulsa and kill an estimated 300 people.

It was later determined that the event was fabricated, in other words, “a big lie.” Mr. Rowland was later vindicated, but the damage to the Tulsa community and the loss of life could not be undone. Today, we are experiencing a modern day “big lie” that seems to be tearing at the fabric of this country. Hopefully we have learned lessons from the Tulsa Race Massacre that will help maintain the greatness of our fragile democracy.

Greenwood was known at the time as “Black Wall Street” due to its status as one of the most prosperous African American communities in the country. The devastation wrought by the mob, many of whom had been deputized and armed by local officials, took the lives and livelihoods of many in the Greenwood community. It caused irreparable damage to hundreds of Black families, who never received justice for their losses.

I, like many of you, am old enough to remember those little bank books that were issued when you opened a bank account. Those little books were not fireproof and many survivors of the massacre whose only proof of their bank accounts were burned up with their other possessions, never got their money and were never compensated for their losses.

This horrific incident was erased from collective memory when the Tulsa Tribune destroyed all original copies of the May 31, 1921 edition of the newspaper and removed it from any archival copies. Scholars later discovered that police and state militia archives about the riot were missing as well. We cannot overcome the issues of race that have troubled our nation since its inception by ignoring the failings of our past.

I often quote Alexis De Tocqueville’s notion that America’s greatness lies not in being more enlightened than any other nation, but rather because it has always been able to repair its faults. To repair our faults, our country must acknowledge past mistakes and work to ensure we don’t repeat them.

I believe this anniversary gives us the opportunity to remember this dark past and recommit ourselves to finding ways to address racial inequities by taking steps that are necessary to repair the faults of our past. Working together, with informed acknowledgments and our eyes wide open, we can make significant strides in our “pursuit of a more perfect union.”