It is the sacred wisdom of our ancestors that a great person lies down in death like a hill, still having height and always pointing the way upward, constantly calling us to the upward paths of our best ideas, values and practices as persons and a people. And so it is with our beloved and honored brother, Larry Aubry, an all-seasons soldier and uncompromising servant of his people, who made transition and ascension, Saturday, May 16, 2020 (6260), and now sits in the sacred circle of the ancestors, among the doers of good, the righteous and the rightfully rewarded.

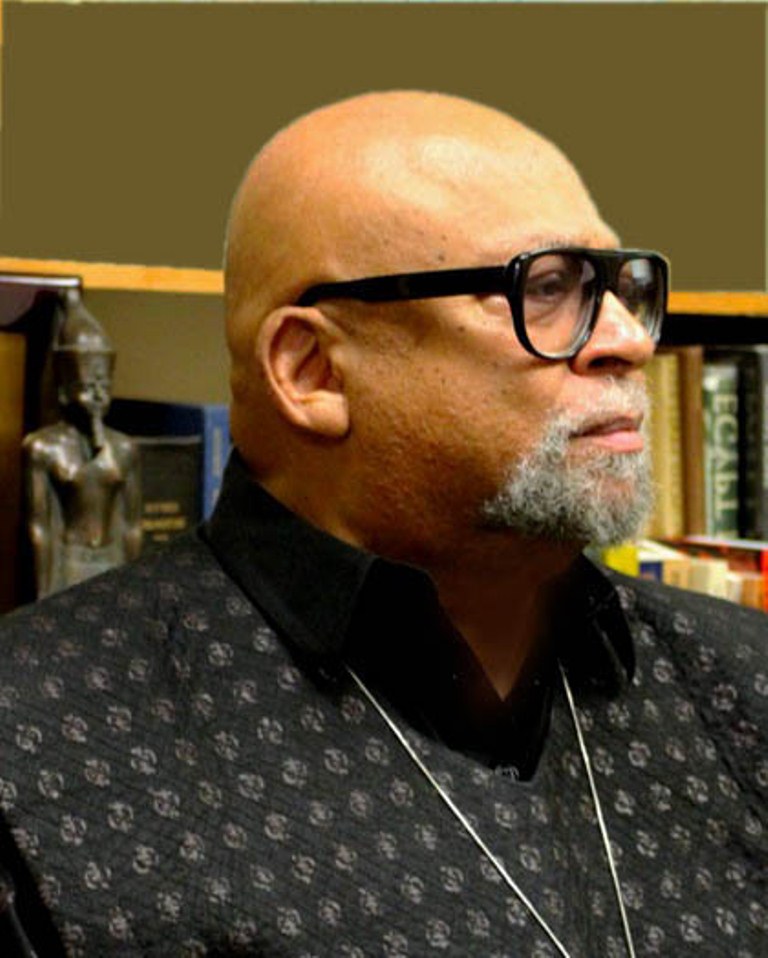

We know Larry by the many areas of life in which he did his self-defining work, by the enriching relationships we shared with him and by the dignity-affirming ways in which he presented himself. Thus, he was first and foremost in the context of community, an uncompromising servant of his people. Serving them in multiple ways, he was community leader, columnist, union activist, human relations and educational consultant and advocate, organizer and musician. And he was beloved husband, father and friend, negotiator, mentor, counselor and comrade and co-combatant in the righteous and relentless struggle for Black liberation and racial and social justice.

Larry leaves an awesome life-time legacy of service, institution-building and righteous and relentless struggle. And thus, his passing is a great and irreplaceable loss to us all and to our ongoing struggle to expand the realm of freedom, justice and good in every area of life. But he can and must remain among us if we honor his life by embracing and living his legacy. Therefore, to honor him rightly, we must remember him rightly and act on that sacred memory.

To rightly remember and honor Larry Aubry is to recognize, appreciate and strive to emulate the long length and value-grounded variousness of his service for the Good, the depth of love for his people, and his uncompromising commitment to them and their struggle for liberation and racial and social justice. It is also to understand, appreciate and emulate his profound commitment to his family and how he linked family and community and his obligations to both. He will be greatly missed and will, if we rightfully honor him, always serve as a model and mirror of dedication, discipline, sacrifice and honored achievement,

It is an ongoing, ever-freshly felt honor to have worked together with him over the years as friends, fellow leaders, co-chairs, co-workers and co-combatants in this sacred and beautiful struggle for liberation to bring and sustain good in the world. We had met and worked together in the Black Freedom Movement of the Sixties during the Black Power Period. He was CEO of the Opportunities Industrialization Center (OIC), founded by Rev. Dr. Leon Sullivan, a major civil rights leader, with branches in the U.S., Africa, Haiti and elsewhere, directed towards economic education, skill acquisition, employment and empowerment. I had served on his board as a representative of our organization Us, as part of our programmatic stress on operational unity, unity in diversity and struggle on many fronts.

Having worked together on various Black united front projects in the Sixties, in the 80s we began to work together with Rev. Eric Lee, then president of SCLC-LA. And he became one of the early founders with us of the Black Community, Clergy and Labor Alliance (BCCLA), a Black united front engaged in the advancement of the interests of Black workers and the well-being of the Black community as a whole, and we served as co-chairs until his passing. We also shared conversations and planning in the policy discussion group, Advocates for Black Strategic Alternatives (ABSA), which he founded.

Larry was an organic activist intellectual who loved studying, discussing and actively engaging the critical issues confronting our community. He joined his intellectual work with his activist initiatives, writing a column for the Los Angeles Sentinel for 33 years. Indeed, he noted this in his last column in the Sentinel saying, “My writing has always been rooted in my activism in the community. It formed my choice of topics, the particular position I took and the evidence and arguments I gave to prove and explain the points I made.” He was speaking here of drawing from a long-term lived experience and practice. And he wrote that he appreciated that the Sentinel had given him “the space and opportunity to write from an unapologetically Black perspective on issues important to our community.”

Writing from the life he lived, the work he did and the struggle he waged as an all-seasons soldier, Larry, reporting from the frontlines writes, “I wrote a lot on education because I do much of my work in this area and think it is critical to the development and success of our young people and the community as a whole.” This work done over the years included fighting to desegregate Fremont High School as a student, and later serving as vice-president and chair of education in the Los Angeles NAACP, board member for the Inglewood United School District, and most recently chair of the Education Committee of BCCLA. He also advocated at the LAUSD and led the initiative through BCCLA to draft, support and elect Dr. George McKenna (District 1) to LAUSD, and to achieve a culturally responsive quality education and educational equity throughout the district.

He also wrote and struggled against police violence, for “it’s clearly a matter of life and death on a daily basis,” he said, not only in terms of the targeting (miscalled profiling), shooting and killing Black males and females, but arbitrary arrests and brutal beatings, gang misidentification and suppression, and denial of the right of presence and security, even in our own homes. He wrote and worked also for just treatment and programmatic development for Black males, not to diminish or divert from needed programs for Black females, but for a balance of attention and initiatives to build family and community. He also wrote against sexism and domestic and communal violence and worked in and with organizations dedicated to issues of peace, security and cooperative building and struggle, for example, the Inglewood Coalition for Drug and Violence Prevention and the Community Call to Action and Accountability with internal and external initiatives.

A long-time union activist, Larry wrote on labor issues and worked within and with unions and community organizations to achieve employment and economic justice, equity and empowerment initiatives for Black workers and the Black community. In addition, he served as vice-president of the A. Phillip Randolph Institute, member of the founding committee of the Los Angeles Black Workers Center, and again is a founding member of BCCLA, dedicated to the economic and related life issues of the Black community.

Recognizing with Min. Malcolm, whom he admired, the national and global status and interests we have as an African people and the international reach of our oppressor, he spoke constantly of the need for alliances and coalitions across the country and internationally. Thus, he built multicultural alliances, including the Black/Latino Roundtable, the Black/Korean Alliance and the Multicultural Collaborative. And he stressed also “the importance of working with and building mutual support of workers in other countries, given the international character of capitalism and labor issues.”

Seeing reparations as an important moral and economic issue, he advocated for reparations and criticized universities and colleges for their role in enslavement and the country for its legitimation, defense and practice of enslavement. As a member of the Black Alliance for Just Immigration (BAJI) and the Black Immigration Network (BIN), he struggled to ensure inclusive and just immigration policies and practices, racial and gender equity, and the solidarity of African peoples, domestically and internationally.

Larry was a man rooted in Black culture, not only in its creative and social practices, but especially in its values. He had observed that one of the great problems for both Black life and struggle are those who “have internalized European values without access to their benefits.” He maintained “that we must reembrace strongly values that stress our collective interests and not continue to emulate whites’ individualistic and materialistic values.”

In this regard, he also saw our culture and our struggle calling for us to approach leadership as a moral vocation. It is a leadership, he said, that is ethical in its practice and pursuit of policies, committed and accountable to the people, and supported by a people that holds itself and its leadership accountable. For he understood and believed Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune’s teaching that “The measure of our progress as a race is in precise relation to the depth of faith in our people held by our leaders.”

In a reflection on return to New Orleans after having left at an early age, Larry reveals the early family and community sources of his sensitivity to others, his love of family and commitment to family and community. His grounding first comes from a strong and resourceful widowed mother, deeply rooted in the Catholic faith and Black cultural values of caring, sharing, sacrifice and struggle, and achieving “the wholly impossible.” It was his memory and model of “Mama searching to find her way after daddy died, my seven brothers, struggling to order their lives in the midst of the Depression, but each unfailingly helping Mama.” And “sharing even our meager resources with our neighbors.” And it was his Creole community in New Orleans in the 7th ward and a larger Black community in South Central L.A. that raised up and reaffirmed the good of “close bonds and sharing” and the striving and struggling together that grounded relationships and taught him the upward paths of his culture.

Family, then, was central to him. And everyone who knew or heard about Larry, knew how he loved his wife, Gloria, and regardless, really irregardless, would stop, suspend and leave whatever else he was doing and rush home every Friday without fail to create and share the good of just being together and doing and feeling the beauty of it all. And he was also supportive and encouraging to all his children and worked for their success and strength. But again, he linked family and community and strived mightily to fulfill in his obligations to both.

He remembered fondly when Central Avenue was alive with Black life, love and joyous celebration, with a strong sense of family and community and a profound “sense of caring and sharing.” And he urged us all to intensify our efforts to build and strengthen family and community. Indeed, he tells us that his visit home back to New Orleans in the 80s was “a vivid reminder of how fortunate I am to be Black and part of a proud Creole family and culture. It reaffirmed a legacy of love, strength and caring for which I am forever grateful.” He had rejected Creole color consciousness, clannishness and other negatives even as he had done so for the larger Black community. But he saw good in each and built on their strength.

He constantly urged us to keep the faith and hold the line, to care and share, and struggle ceaselessly for a new community, society and world. In an interview, he said of this journey, “We have a long way to go, but I’m looking forward to getting there.” And, of course, he will indeed get there when we do. For he will live in his work and achievement and by our advancing and winning the sacred struggle to which he and all our ancestors dedicated their lives. And as it is written in the sacred texts of our ancestors, The Husia, this is our commitment: he will always be for us “a glorious spirit in heaven and a continuing powerful presence on earth. He shall be counted and honored among the ancestors. His name shall endure as a monument. And the good he has done on earth shall never perish or pass away.”

Deferring to Larry for the last word concerning his life, I end with a quote from his last column in the Sentinel. And he says to us, “If there’s one lesson summing up what I’ve learned and would like to share, it is this: we must unapologetically take control of our own destiny, develop and pursue our own agenda, build appropriate coalitions and alliances, and continue to struggle for racial and social justice without compromise. We are a proud and resilient people, rich in internal resources, and whatever meaning and value this column and my work has had, it’s because I have continuously drawn from those resources and used them to strengthen and guide my efforts. Finally, I thank you, the community, and you the readership, and of course my wife and family, and my colleagues and friends for accompanying me on this gratifying journey and for your support and creative challenge, Unity, Strength and Determination.” Hotep. Ase. Heri.

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.