Again, this year we wish for Africans everywhere throughout the world African community “Heri za Kwanzaa. Happy Kwanzaa.” And we bring and send greetings of celebration, solidarity and continued struggle for an inclusive and shared good in the world.

Also, in the still-held-high tradition of our ancestors, we wish for African peoples and all the peoples of the world all the good that heaven grants, the earth produces, and the waters bring forth from their depths. Hotep. Ase. Heri.

Moreover, among all the goods that are granted, given, and gained through ceaseless striving and righteous and relentless struggle, we wish, especially for our people and all other oppressed and struggling peoples of the world, the shared and indivisible goods of freedom, justice, and peace, deservedly achieved and enjoyed and passed on to future generations.

Indeed, we live in turbulent times of continuing unfreedom and oppression, the enduring evil of injustice and destructive conflicts, and unjust and genocidal war. And freedom, justice, and peace in the world and for the good of the world and all in it are urgent, essential, and indispensable.

Thus, we are morally called, commanded, and compelled to bear witness to truth and set the scales of justice in their proper place, especially among the voiceless and devalued, the downtrodden and defenseless, the oppressed, and the different and vulnerable. And we must do this not only through speech, but also in the way we live our lives, do our work, and wage our struggles for shared good in the world.

Kwanzaa was conceived and born in the womb, work, and transformative struggles of the Black Freedom Movement. And thus, its essential message and meaning was shaped and shared not only in sankofa initiatives of cultural retrieval, of the best of our views, values, and practices as African peoples.

It was also shaped by that defining decade of fierce strivings and struggles for freedom, justice and associated goods waged by Africans and other peoples of color all over the world in the 1960s. Kwanzaa thus came into being, grounded itself and grew as an act of freedom, an instrument of freedom, a celebration of freedom and a practice of freedom.

It was an act of self-determination and self-authorization; a means of cultivating and expanding consciousness and commitment; a righteous reveling in our recaptured sense of the sacredness, soulfulness, and beauty of our Black selves; and the practice of principles that engenders and sustains liberated and liberating ways to understand and assert ourselves in the world.

And at the heart of this liberated and liberating practice are the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles of Kwanzaa and of Kawaida philosophy out of which I created both Kwanzaa and the Nguzo Saba. Kawaida defines itself as and strives mightily to bring forth the “the best of African sensibilities, thought and practice in constant exchange with the world” and thus is developed and directed in the interest of African and human good and the well-being of the world.

If we are to achieve these vital goods and the new world that their securing will require and reflect, then, we must have principles and practices that ground and direct us toward this noble and needed goal. And the Nguzo Saba, the Seven Principles, offer us these principles and practices. Umoja (Unity) calls on us to work and struggle for principled, purposeful and practiced togetherness in freedom, justice and peace in our families, communities and the world. It stresses the ties that link us and cultivate in us sensitivity to each other, other humans and the world and all in it.

Indeed, it is expressed in the teaching of Nana Dr. Anna Julia Cooper who affirmed this ancient and African value. She says, “we take our stand on the solidarity of humanity, the oneness of life and the unnaturalness and injustice of all favoritism whether of sex, race, condition or country.”

Kujichagulia (Self-Determination) reaffirms the fundamental principle and practice of the right of every people to determine their own destiny and daily lives, to live free in their own place, space and time. And it reaffirms the right to resist all forms of unfreedom, injustice and oppression. It reaffirms Nana Haji Malcolm X’s teaching that “freedom is essential to life itself. Freedom is essential to the development of the human being. (And) If we don’t have freedom, we can never expect justice and equality.” Indeed, “only after freedom do justice and equality become a reality” in the fullest sense of the principle and practice.

Ujima (Collective Work and Responsibility) reminds us and reaffirms the enduring and essential truth that we must build the good world we all want and deserve. It teaches the centrality of togetherness in our constant quest for an inclusive freedom, justice, and peace. And it reaffirms the reality that only in collective work and responsibility can we achieve freedom, ensure justice, and build the peace and security of persons and peoples we all long and struggle for all over the world.

And as Nana Dr. Mary McLeod Bethune taught us, “Our task is to remake the world. It is nothing less than this.” And we must do this together, for freedom, justice, peace, and other goods are indivisible and they are vulnerable and unattainable in isolation.

And we know from the hard lessons of history and the irreducible requirements of our humanity that there can be no peace without justice, no justice without freedom and no freedom without the power, will and struggle of the peoples of the world to achieve and sustain these shared and vital goods.

Ujamaa (Cooperative Economics) teaches us the principle and practice of shared work and shared wealth. Modeled on the shared harvest, it calls for cooperative work, respect of the rights of the workers and the needs of everyone for a life of dignity and economic security and the conditions and capacities to live a free, good, and meaningful life. It is rooted in the concept of kinship with and caring kindness toward others and the earth and cultivates a sensitivity for avoiding and resisting injuries to fellow humans and the natural world.

The principle and practice of Nia (Purpose) calls us to do good in and for the world, to pursue and practice freedom, justice, peace, caring, sharing and all that contributes to African and human good and the well-being of the world and all in it. Indeed, the ancestors teach us in the Odu Ifa that we should do things with joy for humans are divinely chosen and righteously challenged to do good in the world. And they remind us in the Husia that the good we do for others we are also doing for ourselves, for we are building the good and promising world we all want and deserve to live in and to leave as a storehouse of good for those who come after.

The principle and practice of Kuumba (Creativity) commits us to work and struggle for a new world and a new us that is rooted in the ancient African ethical imperative of serudj ta which is a moral obligation to constantly repair, renew and remake the world, making it more beautiful and beneficial than we inherited it in the process and practice or repairing, renewing and remaking ourselves.

It teaches and urges us, in our relations with each other, others and the earth, to raise up what is in ruins, to repair what is damaged, to rejoin what is separated, to replenish what is depleted, to set right what is wrong, to strengthen what is weakened, and to make flourish that which is fragile, insecure and undeveloped.

And the principle and practice of Imani (Faith) teaches us to believe in the good and strive constantly to achieve it everywhere and in its most essential, inclusive and expansive forms. It reminds us that we must have faith in the future and the new world we seek to bring into being in order to imagine and build them.

And it is a faith that teaches us to believe that through hard work, long struggle and a whole lot of love and understanding, we can with other oppressed, struggling and progressive peoples reimagine and redraw the map of the world and put in place and develop conditions and capacities for everyone to live in dignity-affirming, life-enhancing and world-preserving ways and come into the fullness of themselves.

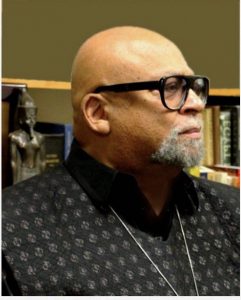

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org, www.MaulanaKarenga.org; www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.Us-Organization.org.