At 17, Juan Rayford Jr. was like so many other teens with big dreams – he wanted to escape his hardscrabble neighborhood and play college football and perhaps make it into the NFL.

But a fateful 2004 night in the northern Los Angeles County city of Lancaster, quickly turned those dreams into a lifelong nightmare.

Rayford had just returned to school to complete credits toward his diploma and what he’d hoped would be a shot at playing football, or, at minimum, a shot at getting out of the city that sits north of Los Angeles and the crossroads of the steamy hot and dry Antelope and Mojave deserts.

Rayford’s mother moved him to Lancaster to keep her son away from the influence of the gangs and violence that have led to as much bloodshed as Rayford’s dad, Juan Rayford Sr., saw in all of his years in the military.

Rayford’s parents were divorced, but both pushed for their child to succeed.

However, they were both aware that the Antelope Valley wasn’t immune to gangs and the related complications that are too often visited upon young African Americans, especially where law enforcement and (ultimately) America’s system of justice are involved.

While at a house party with some friends, Juan Jr. ducked into the back of the hosts’ home to play video games. While there, he said he heard the commotion between a friend and another individual.

“The friend and the other guy had a long-standing beef and it spilled over to a fight and Juan and everybody came running,” said Juan Sr., who lived in Virginia at the time of the incident and now lives in Texas. “Shots were fired, and when the police came, they took names and wanted to know who did what.”

“My son did nothing wrong, he had no gun and there were some shots fired but nobody was hit, nobody was hurt,” he said.

After questioning everyone there, prosecutors appeared to hone in on Rayford Jr. and another teen, Dupree Glass.

Although no one was shot or injured and the home owner and other witnesses initially said the teens weren’t involved, or at least did not possess a gun, Rayford Jr. and Glass were charged with 11 counts of attempted murder.

At trial, both Rayford and Glass were forced to depend upon overworked public defenders. They were offered a deal: 15 years in prison.

“I’m not guilty,” Rayford Jr. pled to his father and all who would listen.

His plea, however, fell on deaf ears.

Zealous prosecutors, who successfully requested bail set at $11 million, piled on.

On October 25, 2004, Juan Rayford Jr. was sentenced to 220 years, plus — 11 life terms.

Glass received a similar sentence.

The sentences appear to violate the Eighth Amendment to the United States Constitution.

“My son’s sentence is manifestly excessive, which constitutes, in effect, cruel and unusual punishment,” Rayford Sr. said. “The only witnesses for the prosecution were the owner of the house and her 15-year old daughter,” Rayford Sr. said.

“The mother and the daughter gave statements to the police the night the incident occurred, which stated that Juan Jr. was there, but he was not one of the shooters.

“At the trial their statements changed, and Juan Jr. had a court appointed attorney who called no witnesses on his behalf,” he said.

Legal experts said it defies reason and proportionality as the Eighth Amendment forbids extreme sentences that are ‘grossly disproportionate’ to the crime and directs judges to exercise their wise judgment in assessing the proportionality of all forms of punishment.

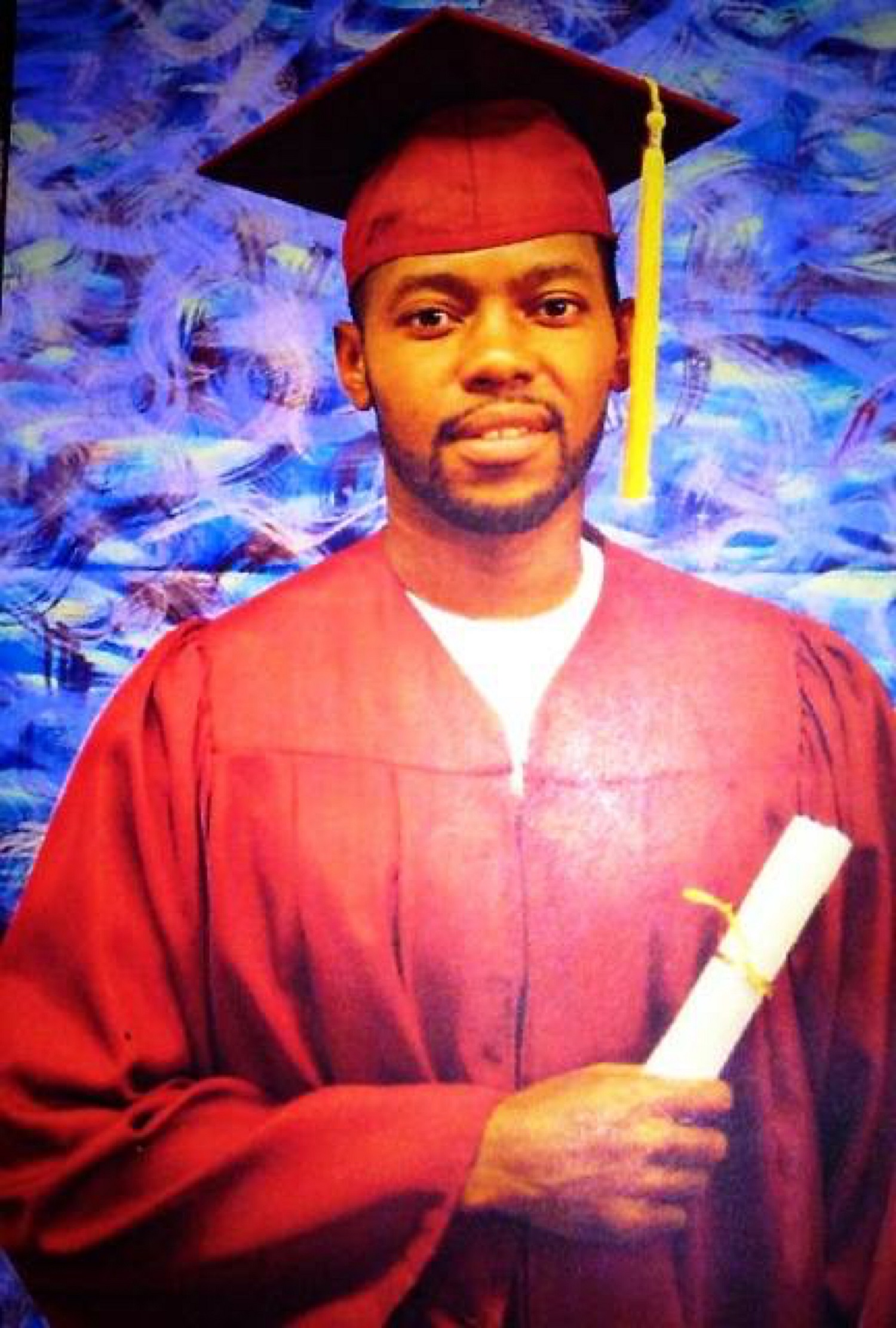

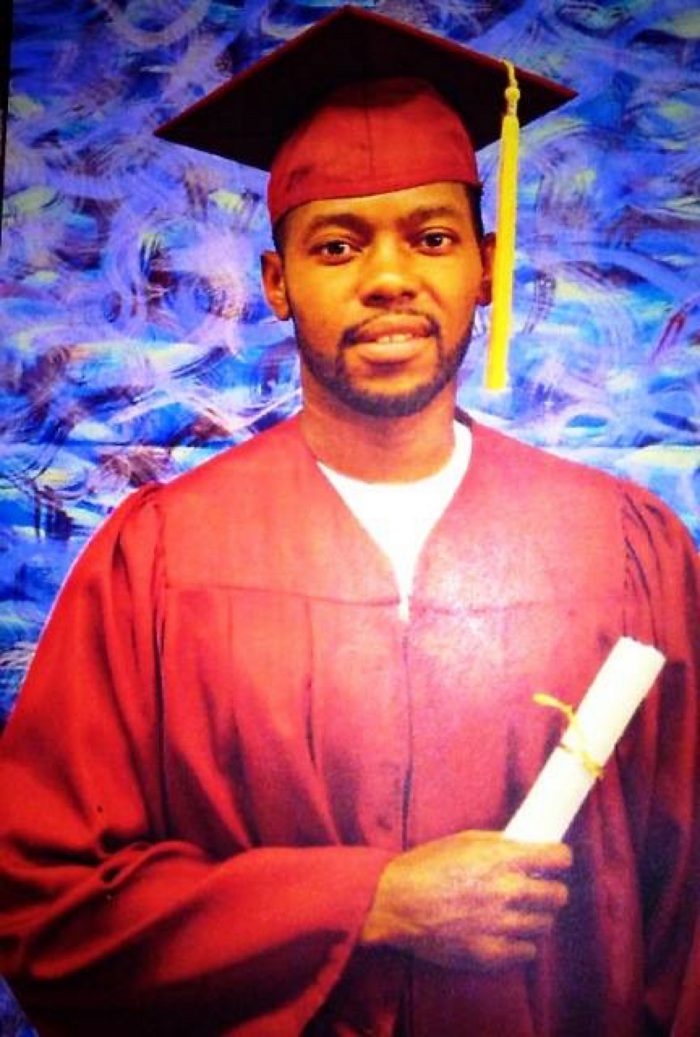

Now, 32 years old, having been incarcerated for 15 years, Rayford Jr. remains in a San Diego-area prison with freedom now his primary dream.

Meanwhile, his father fights daily for him.

In 2012, Rayford Sr. wrote a letter to then-U.S. Attorney General Eric Holder seeking relief, but there was no response. Most recently, he’s written to California Attorney General Xavier Becerra, an outspoken proponent of Criminal Justice Reform.

Becerra’s spokesman told NNPA Newswire that the case is headed toward the state Supreme Court and, therefore, he couldn’t comment.

A 2012 Human Rights Watch report noted that the state of California had de facto sentenced 301 people to die in its prisons for crimes they committed when they were under the age of 18.

They could not be legally sentenced to death — in 2005, the Supreme Court found the death penalty unconstitutional for juveniles.

However, theirs is literally a “life” sentence, having been sentenced to prison for the rest of their lives with no chance of parole or opportunity for release.

Sentences like these underscore how the state of California spends $12 billion annually on its prisons.

Further, Human Rights Watch noted that the United States is now the only country in the world that imposes life sentences on youth

for crimes committed when they were under the age of 18, and that the number of youth given that sentence has continued to increase.

Eighty-Five percent of those sentenced to life terms are individuals of color.

In 2017, then-California Gov. Jerry Brown signed a bill that allows judges to decide against imposing prison-sentence enhancements of 10 or more years in cases where firearms are used to commit a felony.

The state boasts some of the most severe sentence enhancements in the country with more than 100 separate code sections that add years to a person’s prison or jail sentence, according to the Public Policy Institute of California.

One of the most commonly used sentence enhancements was the five year enhancement that comes with the use of a firearm. Using the five year enhancement, nearly 100,000 years have been added to the sentences of people currently in custody.

“I hope this bill will lead to more fair and equitable sentencing in cases involving guns where no one is hurt,” said Democratic Sen. Steven Bradford of Gardena, Calif.

“Longer sentences do not deter crime, but instead disproportionately increase racial disparities in prison populations and they greatly increase the population of incarcerated persons,” Bradford said.

For Rayford Jr. and Dupree Glass, there could finally be some hope.

In 2014, the nonprofit legal entity, the group, Innocence Rights of Orange County, filed writs of habeas corpus on their behalf.

In a statement posted on their website, Innocence Rights of Orange County noted that Rayford and Dupree were sentenced to eleven consecutive life sentences for “allegedly shooting at a house where eleven people lived.

“No one was injured, and Juan has maintained his innocence since day one.

“Nevertheless, he was prosecuted under the Kill Zone Theory which eliminates the need for the prosecutor to prove the element of specific intent when charging attempted murder as long as the individuals are standing within a ‘kill zone.’”

The kill zone is an ambiguous area defined by the prosecutor which results in excessive attempted murder charges.

The petition by Innocence Rights of Orange County was granted by the California Supreme Court in December 2016 and they’re currently waiting for the Court to hear the case.

“Juan isn’t bitter, he isn’t angry,” Rayford Sr., said. “He prays every day and he does what he’s supposed to do and we are hopeful that the Court will soon hear the case and grant his freedom.”