“It is our duty to fight for freedom….It is our duty to WIN…We must love and protect one another….We have nothing to lose but our chains…” a raised-fist, clenched-jaw, teary-eyed, handcuffed Jasmine “Abdullah” Richards chants as she is led out of the courtroom by sheriffs after having been convicted for what was initially called a felony “lynching” charge. The charge comes as a result of Jasmine’s activism around the murder of 19 year-old Kendrec McDade, who was killed by Pasadena police on March 28, 2012. Jasmine initiated the Black Lives Matter chapter in Pasadena after having been activated amidst the Ferguson uprising in 2014 and subsequent organizing in Los Angeles and nationally. As one who was raised in a gang environment and was intimately affected by neighborhood violence, including surviving gun violence herself, Jasmine’s life was transformed by the Black Lives Matter movement. She quickly rose to be a powerful organizer, who resonated heavily among young people from communities like the one she grew up in in Northwest Pasadena.

As her profile elevated, so too, did the targeting by police and the state. Threatened by her ability to challenge young people to question and work to transform the conditions under which they live, police in the suburban city of Pasadena, regularly arrested Jasmine on trumped up charges. Each time the community would support her, and recognize the repression for what it was. So when Jasmine was charged with “felony lynching” for coming to the aid of a Black woman who she believed was being unlawfully stopped by police just yards away from a “Peace March” that Jasmine had convened, the irony was inescapable. How could a Black woman, moving to protect one who she perceived as being unjustly held, be charged with lynching? Wasn’t lynching a term that was used to describe the public execution (usually by hanging) of Black people by a mob of racist, violent White people? How could ushering a Black woman towards freedom be defined as ‘lynching’? Those of us who do academic labor understand that promulgating definitions is a key expression of power. We also understand the power of rendering the invisible, visible.

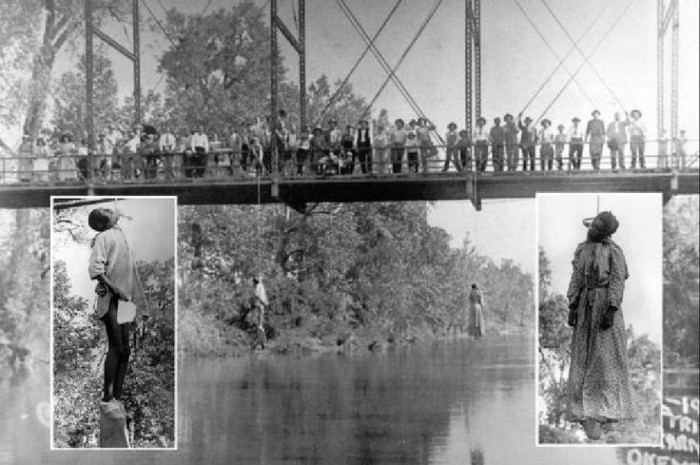

The photograph included here was taken May 25, 1911 in Okemah, Oklahoma. Laura Nelson, a Black woman age 35, was lynched along with her sixteen year-old son after having been taken by a riotous mob from their jail cell. The pair are shown hanging dead from a bridge This photograph was used to create postcards to distribute throughout the country. Lynching, is commonly defined as an extrajudicial murfer – often within a mob environment, and often with the complicity or even direct involvement of the state. Lynching was used both to punish individuals, and to terrorize Black communities. More than 4,000 Black people were lynched in the United States between 1877 and 1950.1 Federal anti-lynching laws, though pushed by Ida B. Wells and the Black women’s club movement, the NAACP, and others, were never passed. Several states, however, including California, passed their own versions.

In a strange perversion, in California, “lynching” has been detached completely from its origins and given a narrow legal meaning devoid of the 1933 lawmakers’ intent. This law has been used recently by law enforcement to abuse the law, and to exact greater legal penalty against those who cross them. Since 2011, when LAPD used the law against the Occupy movement, numerous other activist groups have been targeted with this abusive charge. In recent years, immigration activists in Riverside, Black Lives Matter activists in Sacramento and Los Angeles, and now, in Pasadena, have all been charged in this grossly unjust application of the law.

Notably, when Jasmine “Abdullah” Richards, was originally arrested and charged by African American Los Angeles County District Attorney Jackie Lacey, through her Pasadena lead Michelle Bagneris, the legal term used for California Penal Code 405a was “lynching.” In July 2015, State Senator Holly Mitchell, who is also African American, saw to it that lynching was no longer used to refer to the 1933 legislation. While the impulse to avoid the historic trauma revisited by the use of the term “lynching” in this law is understandable, the original term far better captures the seriousness one would associate with a felony offense. Moreover, the term “lynching” actually captures some aspects of what the “riotous mob” of police and prosecutors have done to activists in the Los Angeles area, and throughout California.

By use of a variety of penal codes, such as that of California Penal Code 405a, to exact a penalty for political dissent, police are allowed to conduct a reign of terror against Black communities. It is incredibly offensive that, with a legacy of abusive and racist police practices in Los Angeles, an African American District Attorney, Jackie Lacey, would agree collude with police in pursuing charges against those who dare to challenge the extrajudicial killings. Rather than utilizing the prosecutorial power of the office of district attorney to charge police officers who killed Los Angeles County residents Kendrec McDade, Ezell Ford, Charley “Africa” Kuenang, Redel Jones, Mitrice Richardson, Wakiesha Wilson, Nephi Arreguin, or any of the hundreds of names that could be noted, District Attorney Lacey, has chosen to prosecute activists. Such charges should give all who truly value freedom and democracy reason to pause.

In fact, misdemeanor cases against Black Lives Matter organizers, activists, and allies are a troubling national phenomenon. However, nowhere else in the nation have misdemeanor and felony charges been pursued with the intensity of Los Angeles. In recent months, Luz Flores and Evan Bunch were convicted for “resisting arrest” for attempting to get the attention of Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti at a public event. There was also the vigorous prosecution of the “BLMLA 7” who were charged after demonstrating on the 101 freeway in November 2014 that resulted in a hung jury. (The prosecutor abandoned plans to retry the case only in the wake of significant public pressure.) There are still pending charges against roughly a dozen Los Angeles area Black Lives Matter protestors.

Extreme criminal prosecution is clearly being used as an intimidation tactic to silence protest. The conviction of activists puts on trial the very notion of nonviolent direct action and protest itself. Jasmine “Abdullah” Richards’ conviction not only works to forestall the power of one of Black Lives Matter’s most visible organizers, it sends a message to others…much like the intent of the public lynchings of the late 19th and early 20th century, that some of the severest of consequences are to be suffered by those who dare to stand up. The question now posed is do Black people have the right to stand up for ourselves. What risks do Black organizers run in challenging the state around its sanctioning of violence? As Black Lives Matter continues to push for a more just and free world, what kinds of repressive “mobs” form? How is the state readying the noose that might serve to silence protestors and all who identify with them? And how, in a distortion of history and justice, is the victim cast as the aggressor?

The irony here is overwhelming. In the wake of what we would describe as a “new lynching era,” where Black people are killed by police without consequence at least every 28 hours, that those who have the courage to stand up and state loudly “Black Lives Matter” are being arrested, and charged is obscene. The police, prosecutors and some elected officials have banded together as a mob, to circumvent justice, exact punishment and to make public examples of those who dare to challenge their abuse of authority. Trials and convictions swing from courthouses – like strange fruit. And it is the protestors who are charged with lynching.

Melina Abdullah, Ph.D. and Angela James, Ph.D., both are locally based professors of Pan-African Studies and organizers with Black Lives Matter-Los Angeles.