As always, the marking of this year’s Earth Day and Earth Month offers us and humanity as a whole an important invitation and opportunity to focus and reflect on our relationship and responsibility to the health and well-being of the natural world. This is not only because we are to constantly demonstrate through priorities and practice our appreciation of the intrinsic value of the earth, but also because the health and well-being of the world is deeply and inseparably linked to that of our own and the whole of humanity.

And this fact is driven home to us, not only in terms of the beauty, wonder and resources it offers us, but also in the disproportionate number and kinds of diseases, illnesses, suffering and deaths we experience when the air we breathe, the water we drink and the land on which we live and in which our food is grown are polluted, poisoned and destroyed, and in our diminished capacity to weather these existential storms.

The narratives of polluted water in Flint, Michigan, toxic landfills in Sumter County, Alabama, and Grays Ferry, South Philadelphia, and Cancer Alley from New Orleans to Baton Rouge, Louisiana are models of the many sites of deadly, disease-causing and devastating conditions imposed on us and other peoples of color similarly situated.

We live in a context in which a racial capitalism and the consumerist culture it has created and sustains puts profit and convenience before the health and well-being of Black people, and others different, poor and vulnerable, and approaches nature as a resource which does not require respect. And thus, racial capitalism with its vicious, violent and vulturine approaches to the world and all in it has brought us to the brink of ecosystem collapse and an existential threat to human existence.

And it is an irony of history and evil of current human society that those who contributed the least to this unfolding ecosystem collapse do and will suffer most from it. Likewise, those least able to cope with it do and will bear its greatest burdens. Thus, the poor and vulnerable in each country and the island nations who are being slowly submerged by melting glaciers and rising ocean waters and who contributed least to climate change are and will be most affected by the greed and criminal conduct of others.

For it is, indeed, crimes against nature and humanity, this war being ruthlessly and relentlessly waged against the world and ultimately all in it. Here the practice of reparations, debt cancellation and appropriate funds for damage done and the needed repairing, renewing and remaking their lives and lands and, indeed, the world are in order and urgent.

Thus, to escape collaborating in our own oppression and threatened extinction and the destruction of the planet, we must change the way we relate, act and walk in the world. Indeed, as Nana Frantz Fanon urged us, “It would be well to decide at once to change our ways. We must shake off the heavy darkness in which we were plunged and leave it behind. The new day which is already at hand must find us firm, prudent and resolute.” For ours is a world-encompassing, world transformative task which includes not only the natural world itself but also our societies and ourselves.

This means a radical rethinking and rejecting of corporate, consumerist and antilife values and practices. Here the Kawaida Maatian ethical imperative of serudj ta is most relevant and urgent, for it requires that we repair, renew and remake ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, renewing and remaking the world. It requires also that in doing this, we relate rightly, act justly and walk gently in the world.

To relate rightly, we must embrace an identity that reveals and reaffirms the unity of being, the oneness of life, and the interrelatedness and interdependence of the whole world which ultimately includes us. Nana George Washington Carver, naturalist, conservationist and environmentalist, taught the oneness of being, an “organic unity” of the world, and the “mutual relationships of the animal, mineral and vegetable kingdom.”

And he spoke of “how utterly impossible it is for one to exist in a highly organized state without the other.” And Nana Wangari Maathai calls on us to “revive” and reaffirm our ancient African “sense of belonging to a larger family” which includes the world and all in it. In a word, as we say in Kawaida philosophy, we must see and assert ourselves, not only as human beings (watu), but also as world beings (walimwengu).

To act justly in and for the world and for ourselves is to relate rightly in ways that give everyone and everything in the world their rightful due. Here the ancient African Kemetian concept of humans as bearers of dignity (shepesu), an inherent worthiness that is transcendent of all social and biological characteristics, equal in all and inalienable is relevant and urgent. Thus, all are worthy of the highest respect, an equitable share of the common good of the world, and entitled to conditions and capacities for living a good and meaningful life.

And the earth deserves its own respect for its intrinsic value as a goodness in itself, as our ancestors taught, a divine creation and sacred space. And it also deserves respect for what it means and gives to us to sustain, enrich and expand our lives. And therefore, it must be treated justly and also given its due in preservation and protection and an opportunity to unfold in its naturalness.

Dr. Carver teaches us that an essential way we can relate rightly and act justly toward the earth is to be kind to it. Indeed, he says, “unkindness to anything is an injustice to that thing.” It’s important to note and stress here Dr. Carver’s use of kindness as a defining characteristic of justice. This takes justice beyond procedures and procedure observation, and calls on us to be considerate, humane, generous, sensitive and receptive to the other in our conception and practice of justice towards fellow humans and the natural world.

And then we must walk gently in the world. This means moving and asserting ourselves in the world without arrogance and abuse, without the corrosive and inconsiderate weight of overconsumption and waste, and without cooperating in the government sanctioned corporate plunder, pollution and depletion of the world.

We must come to what Nana Maria Stewart called “the field of action” earnestly and actively committed to the serudjic project of repairing, renewing and remaking ourselves and the world and leaving a legacy of good for future generations.

In conclusion, we must claim the future as both a responsibility and promise through righteous and relentless struggle to save ourselves and the earth. It must aim at achievement of equal protection for all against the unfolding catastrophe, especially for the most vulnerable, and the right conditions and capacities for all to participate in every decision critical to the well-being of humanity and the world.

And this will require in the context of our struggles realism and reason in our minds, caring and commitment in our hearts, and audacious agency, resoluteness and resistance to all forms of oppression in our practice.

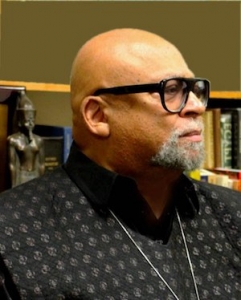

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Introduction to Black Studies, 4th Edition, www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.