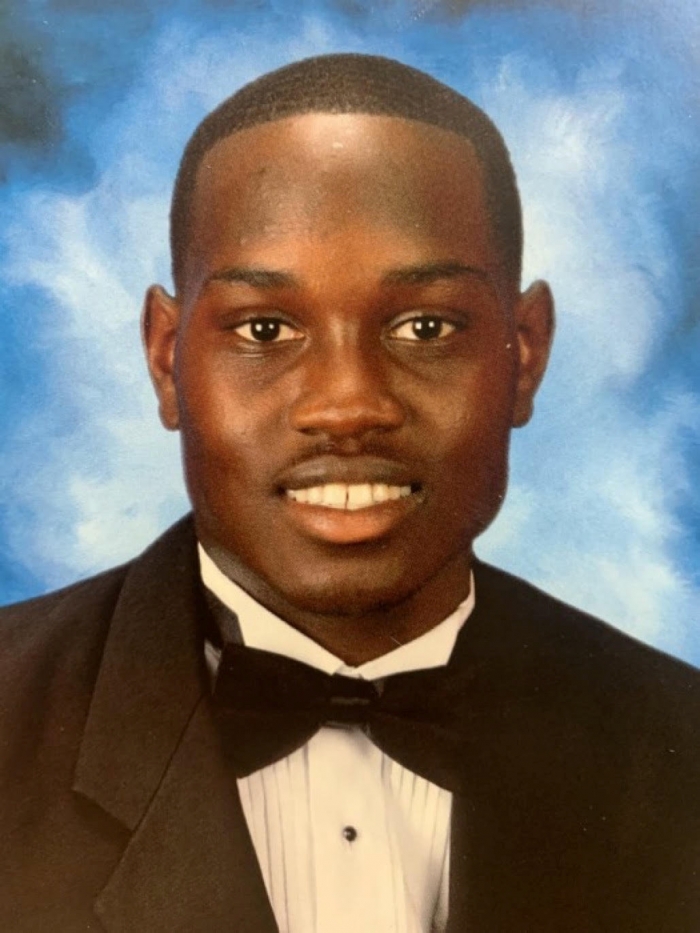

In Georgia, defense attorneys are making the case that the three White men involved in killing Ahmaud Arbery, a Black man, were justified by a Civil War-era law instituted to catch runaway slaves.

Travis McMichael, 35, his father, Gregory McMichael, 65, and their neighbor, William “Roddie” Bryan, 52, plans to defend their actions by claiming they were making a citizens’ arrest that went awry only after Arbery resisted. When the trio killed Arbery on February 23, 2020, Georgia law allowed almost anyone to arrest another citizen if “they had reasonable and probable grounds of suspicion” that a suspect had committed a felony.

The state overturned the statute after Arbery’s murder. Lawmakers introduced and passed the original code in 1863 to capture slaves who had escaped from plantations in the South. “They are going to use this law because it wasn’t repealed until after Ahmaud Arbery was killed by the McMichael family, and I am not sure we’re going to have the justice that we should,” said Shirley James, publisher of the Savannah Tribune in Georgia.

James said Georgia also employs the Stand-Your-Ground law that allows citizens to use deadly force when confronted with life-or-death situations. “The thing that happens a lot, even with George Floyd and a lot of our African Americans who have been unjustly murdered, the victim becomes the criminal,” James remarked. “They are looking at Arbery’s life and he’s deceased and can’t defend himself.”

She added that very few people of color are among the 1,000 prospective jurors, and Glynn County, where the trial will occur, counts as a mostly White area.

“I don’t think in that county that you will find the kind of objectivity that you need,” James demurred. “When you think of the mindset of the things going on now with people so free to speak out in reference to their discriminatory attitudes, they have about us …”

Recent reports suggest that many U.S. states still have laws that allow for citizens to make arrests. Chris Slobogin, a law professor at Tennessee’s Vanderbilt University, told Reuters News Service that citizen’s arrest laws put dangerous powers in untrained hands. “Things can get out of control quickly,” he said.

Roddy Bryan’s lawyer, Kevin Gough, told reporters earlier this month that the “Citizen’s arrest is a big part of our case, a big part.” Ira Robbins, a law professor at American University in Washington, wrote in an academic paper that many states’ citizen’s arrest laws are broad.

In California, for example, someone can arrest an individual for a felony if the person has probable cause to believe it was committed. “While recruiting citizens to aid in eradicating crime is a noble idea,” Robbins wrote, according to Reuters, “strict safeguards are needed to prevent the law being abused.”

New York state has the strictest law, holding residents liable for false arrest if no crime was committed, even if they had a reasonable belief, “leaving no room for mistakes,” Robbins continued.

When Georgia Gov. Brian Kemp repealed the law, he said Arbery was “the victim of vigilante-style violence that has no place in Georgia” and that the statute was “ripe for abuse.”

The ACLU’s Georgia chapter said, “the old law was an example of systemic racism and empowered mobs that lynched Black people in more than 500 recorded cases in Georgia between 1882 and 1968.”

The trial of the McMichael family and Bryan is scheduled to begin on February 7, 2022.