Missing Burundi Teens Highlight Media Blind Spot towards the Black Community

The mainstream media response to the disappearance of a group of teenagers from Burundi, who were in Washington, D.C. for a robotics competition, has once again revealed why covering the stories of missing Black people remains so complex.

The team was in Washington for the FIRST Global Challenge robotics competition. The students went missing in July.

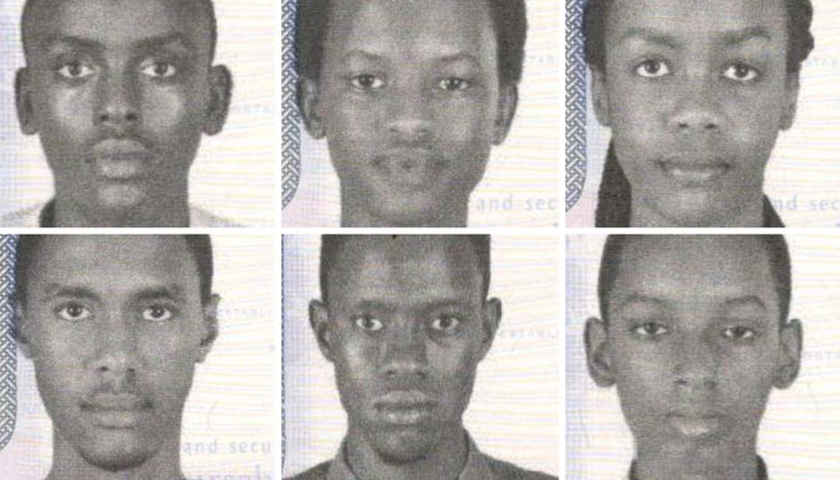

The Washington Post reported that, “two of the teens—Don Charu Ingabire, 16, and Audrey Mwamikazi, 17—crossed in to Canada and were with friends or relatives,” and that police confirmed that, “the other four—Richard Irakoze, 18, Kevin Sabumukiza, 17, Nice Munezero, 17 and Aristide Irambona, 18—were not yet with relatives, but were still safe.”

Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) officials said that they didn’t have any more information about the whereabouts of Irakoze, Sabumukiza, Munezero, and Irambona; the case was still under investigation, according to a story published at NPR.org on July 20.

Human Rights Watch (HRW) reported that Burundi, the East African home country of the missing teenagers, descended into lawlessness in April 2015 when President Pierre Nkurunziza announced his bid for a disputed third term, despite protocols mandating a two-term limit.

HRW found that, over the past two years, government repression has continued and peace talks between the political factions have stalled.

“Hundreds of people have been killed, and many others tortured or forcibly disappeared,” HRW reported. “The country’s once vibrant independent media and nongovernmental organizations have been decimated, and more than 400,000 people have fled the country.”

Although, the robotics team’s coach suggested that family members of the teenagers may have been complicit in their disappearance, the lack of sustained media coverage about the missing African teenagers mirrors mainstream media’s apathetic approach to stories about Black women and children who never make it home.

“A 2016 analysis of online coverage of missing persons published in the Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology found some evidence that cases involving White women not only draw more attention, but more intense coverage,” according to a TIME.com article.

Last spring, amid social media furor about the plight of missing women and girls of color in the District, Washington’s Mayor Muriel Bowser and the Metropolitan Police Department (MPD) defended their decision to use social media to increase awareness about missing people.

It was that use of social media that indirectly contributed to the misinformation about the missing women and girls in the District that went viral.

“Information shared by Washington police with the intention of informing the public was compiled by a popular Instagram account, Entertainment for Breakfast, into an inaccurate post that claimed 14 girls had gone missing in Washington in a 24-hour period on March 23,” the TIME.com article said. “That post went viral, causing celebrities like Taraji Henson, LL Cool J and Viola Davis to sound the alarm. Many “regrammed” the post, sharing inaccurate information even after Entertainment for Breakfast removed the erroneous data from their account.”

Bowser, the Metropolitan Police Department and other city officials held a press conference and issued statements, attempting to quell rising anxiety among residents and to explain the increased social media chatter about the missing girls.

The Final Call reported that a calculated decision by Metropolitan Police Commander Chanel Dickerson to publicize all cases of missing children on social media was at the heart of the anxiety. That action led to “ the mistaken belief that the cases of missing girls had skyrocketed.”

Commander Dickerson, the head of the department’s Youth and Family Services Division said that there was no evidence that any of the missing teens had been kidnapped or involved in human or sex trafficking. She also noted, “that between 2012 and 2016, 99 percent of all missing person cases have been closed,” according to The Final Call.

Although government officials have ruled out human and trafficking, other issues affecting the Black community could help to explain the epidemic.

Fatmata Fadika Zulu, who has been teaching in Baltimore, Md. and Washington for 17 years, said that she witnesses the fallout from homes destroyed by poverty, drug abuse, mental illness and neglect in the classroom every day.

“I asked my students if they knew where the children were going and they said, ‘they’re just running away,’” said Zulu, who has taught 4th and 5th graders, as well as 7th and 8th graders. “The kids came across as unsympathetic and un-empathetic, which I found quite strange. Many of them come from backgrounds with a lack of parenting, drug issues and other problems and they can see why some children are running away.”

Zulu said in the Ward 8 community in which she teaches, not all parents abuse drugs, but some young people aren’t held to any standards of accountability and they have a great deal of free time without adult supervision. More than a few children live nomadic lives, couch surfing or splitting time between family and friends that take them in.

Zulu continued: “I have parents who are active with their children, but unfortunately, this is an extremely small percentage. Parental responsibility is just not happening.”

The mission is to keep talking about this issue in therapeutic ways to deal with the problem, said Zulu.

“We need to build self-love, self-worth, so that as [the children] are being lured into danger, they have the tools to resist,” said Zulu. “We need discussions, panels and teen summits. Policies can lead to true change. We also need sit-downs with teachers and others who work in the trenches.”

In a press statement about the missing children in Washington, Bowser identified, “six immediate initiatives to locate young people who have been reported as missing, provide critical resources to better address the issues that cause young people to run away from home, and support young people who may be considering leaving home.”

Those initiatives include: increasing the number of MPD Officers assigned to the Children and Family Services Division; expansion of the MPD “Missing Persons” webpage and social media messaging to include case catalogs with more information; establishing the missing persons evaluation and reconnection resources collaborative; and providing additional grant support for non-profits addressing runaway youth

“One missing young person, is one too many, and these new initiatives will help us do more to find and protect young people, particularly young girls of color, across our city,” said Mayor Bowser in the statement. “Through social media, we have been able to highlight this problem and bring awareness to open cases, and now we are doing more to ensure that families and children are receiving the wraparound services they need to keep families together and children safe.”