Donnie Shell has been compared to a member of a great band from which many other artists already had received top accolades.

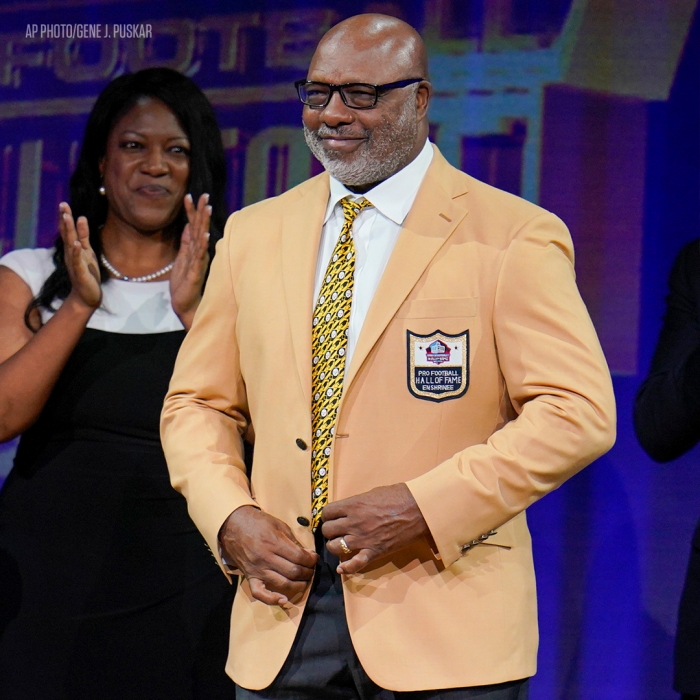

But to keep up with the others in that group, Shell needed to be just as accomplished. And now he has been recognized for his skills, being inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of the centennial class.

Shell was a linebacker at South Carolina State who went undrafted, was shifted to safety in Pittsburgh and became a tackling machine. With veterans on strike in his rookie year of 1974, Shell made such an impression that coach Chuck Noll inserted him as a starting safety. He spent 14 seasons as a fixture for the Steelers.

With hundreds of Terrible Towels waving, Shell recognized Steeler Nation and then said of being an undrafted free agent from South Carolina State, “When facts get in the way of your goal, you must go against the grain to achieve your goal.”

___

Judging the value of blockers is a tricky proposition. Not when it comes to Steve Hutchinson.

The outstanding guard for 12 NFL seasons _ five with Seattle, six with Minnesota and one with Tennessee _ was the prime reason running backs on his teams were practically unstoppable with him leading the way. And his performances have led Hutchinson into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Hutchinson was a five-time All-Pro and member of the NFL 2000s All-Decade Team. Along with strong work as a pass protector, he opened holes for rushers who averaged just under 1,400 yards and 14 touchdowns a season.

“If you told me after I graduated from the University of Michigan that I’d be excited standing in Ohio in the middle of August,” he joked, “…to me, there’s no place better than Canton, Ohio.“

Hutchinson then told his son not to “fear failure but fear to have not given my all.”

___

When Paul Tagliabue succeeded Pete Rozelle as NFL commissioner, the challenge already was monumental. Rozelle generally is considered the most successful league leader in sports history.

Then Tagliabue was faced with so many more obstacles, from the outbreak of the Gulf War to 9/11 to Hurricane Katrina during his stewardship from 1989-2006. His skills at overcoming those tests, keeping labor peace, guiding the NFL through expansion, significantly increasing revenues and helping pass the Rooney Rule have led to his induction into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of the centennial class.

“This is like a dream come true,” he said. “The centennial class spans pro football history.”

Tagliabue noted that he took Rozelle’s advice to “think league first.”

“I wanted to keep his bedrock principle in mind,” Tagliabue said.

___

Steve Atwater was considered by his peers _ including other safeties _ the most punishing tackler in the NFL. Such work, along with leadership traits and a knack for big plays, has led to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Atwater, a mainstay in Denver for 10 seasons, including two Super Bowl victories, and a final year with the Jets, was at his best in big games. In the Broncos’ Super Bowl victory against Green Bay, he had six tackles, a sack and two pass breakups.

With a stunning 1,357 tackles, Atwater made the NFL 1990s All-Decade Team, and might be best remembered for leveling Chiefs running back Christian Okoye, who outweighed Atwater by 40 pounds.

“I am humbled and honored to wear this gold jacket,” Atwater said before looking around at the other Hall of Famers on the stage. “What a group we have up here.”

___

When the Colts selected running back Edgerrin James with the fourth overall draft pick in 1999, many observers shook their heads that Indianapolis passed on Heisman Trophy winner Ricky Williams.

The head shaking soon stopped as James established himself as one of the NFL’s best rushers, and they surely have ceased now that James has been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

Called “the best teammate I ever played with” by Peyton Manning, James led the league in rushing his first two seasons. He then overcame a severe knee injury to remain a major force in Indy before finishing his career with three seasons in Arizona and one in Seattle.

James immediately paid tribute to his mother during his speech.

“To my mama, we’re here,” he said with a chuckle. “No blueprint, no manual, and most importantly no man. I’m your man.”

He also delivered a message to society: “Just do your job. If everyone would do their job, the whole world would be a better place.”

___

Hard-hitting safety Cliff Harris has gone from Ouachita Baptist University to the Pro Football Hall of Fame.

The standout tackler and cover man for the Dallas Cowboys from 1970-79 has been inducted as part of the centennial class.

Harris went from a small school (NAIA) star to an undrafted rookie who started from the outset in Dallas. Known almost as much for the high-top shoes he wore as for his heavy and sure tackles, Harris made the NFL 1970s All-Decade Team, earning the nickname Captain Crash.

He also had to juggle National Guard duties during his first few NFL seasons, sometimes reporting for duty during the week and usually getting to rejoin his teammates for games.

“We were the Doomsday Defense.” Harris recalled. “The odds of me playing in the NFL, much less me standing here tonight, were incredibly long. I may be the only one who knows how truly slim that chance was, but if I could make it, anyone can achieve their goals. The key is to never quit.”

___

Harold Carmichael, who dominated defensive backs with his 6-foot-8, 225-pound size and great hands, has been inducted into the Pro Football Hall of Fame as part of the centennial class.

The Philadelphia Eagles star receiver from 1971-83 who finished his career with one year in Dallas had three 1,000-yard seasons in an era when the passing game was not as prominent as it is today. He averaged a touchdown every 7 1-2 catches and made the NFL 1970s All-Decade Team. Carmichael was the league’s Man of the Year in 1980.

“Whew, Baby,” Carmichael said when his bust was revealed. “I am so, so honored to be a part of this brotherhood, this fraternity, with love. What a journey.”

___

Eight members of the centennial class of 2020 are being recognized posthumously with video tributes at the Pro Football Hall of Fame induction ceremonies. All eight were enshrined in a special ceremony in April and now take their place with the rest of the 2020 class, which is being inducted a year later due to the coronavirus pandemic.

Those being honored posthumously are Bobby Dillon, Winston Hill, Alex Karras, Steve Sabol, Duke Slater, Mac Speedie, Ed Sprinkle and George Young.

Dillon was a star safety for the Packers in the 1950s, before Vince Lombardi arrived. Despite having lost one eye in a childhood accident, Dillon made four All-Pro teams and intercepted 52 passes _ second overall when he retired to Emlen Tunnell.

Hill was one of the AFL’s premier blockers, a tackle who protected Joe Namath’s blind side as the Jets won the third Super Bowl and cemented the credentials of the upstart league. Hill still holds the Jets’ franchise records for offensive linemen with 195 straight games played and 174 consecutive starts.

Karras became renowned for his acting, particularly his punchout of a horse in the flim “Blazing Saddles.” But he was a fearsome three-time All-Pro defensive tackle for bad Lions teams and had only one playoff performance. He also was suspended for the 1963 season, along with Green Bay Packers star running back Paul Hornung, for gambling.

Sabol was the driving force of NFL Films. He joins his father Ed, who was enshrined in 2011, as the third father/son duo in Canton. While it was Ed Sabol who persuaded Pete Rozelle in 1964 that the league needed its own film company to promote and document the game, it was Steve Sabol who was creative mastermind. He made the game and players appear larger than life through cinematography, slow motion replays, orchestral music and putting microphones on players and coaches.

Slater was one of the first great Black players in the NFL. Slater tackled bigotry head-on, and blocked it, too. He was the NFL’s first African-American lineman _ even playing for a while with no helmet _ and often the only Black player on the field. After retiring, he broke down more racial barriers to become a judge in Chicago.

Speedie brought, well, speed to the championship Browns clubs of the AAFC, and then into the NFL. The surehanded receiver overcame a childhood disease and later delayed his playing career to serve in World War II. He led the All-America Football Conference in receptions three times and had the most catches in the NFL in 1952, when he had 62 for 911 yards and scored five touchdowns while being chosen MVP on a team loaded with stars.

Sprinkle was considered one of the hardest hitters in pro football for 12 seasons with the Bears. Ron Wolf, himself a Hall of Famer as a contributor, said Sprinkle “was one of the few guys that played back then (1944-55) who could play today.” Sprinkle made four Pro Bowls and the Team of the Decade for the 1940s as a defensive end.

Young was the general manager who helped turn around the fortunes of the Giants. A former high school teacher, coach and later NFL front-office executive, he was the league’s Executive of the Year five times and the team won two Super Bowls during his tenure.

___

The owner of the Atlanta Falcons is using the induction of former NFL Commissioner Paul Tagliabue to the Pro Football Hall of Fame to sponsor a fellowship for a recent college graduate from a Historically Black College and University.

Blank, who has a foundation in his name, has gifted the endowment for two years in Tagliabue’s honor through the James Harris-Doug Williams Fellowship. Honorees work at the Hall in various departments.

Tagliabue pushed for career advancement and diversity in football while he was commissioner. The NFL adopted the Rooney Rule, named for former Pittsburgh Steelers owned and Hall of Famer Dan Rooney, under Tagliabue’s watch and he was a driving force behind passage of the rule that requires teams to interview at least one minority candidate when hiring a head coach.

The rule since has been expanded to general manager and executive positions across the league.

“His impact on the game during his tenure as commissioner is immeasurable,“ Blank said. “Simply put, the NFL wouldn’t be what it is today without him.”

Akil Blount, son of Hall of Famer Ml Blount, was the first James Harris-Doug Williams fellow at the Pro Football Hall of Fame. He now is an employee of the marketing team at the hall.

___

Lynyrd Skynyrd has withdrawn from the Pro Football Hall of Fame concert after band member Rickey Medlocke tested positive for COVID-19.

The band was set to co-headline the concert Monday night with country artist Brad Paisley, with Jimmie Allen opening the show. But Medlocke’s positive test forced the group’s withdrawal.

In a statement through its publicist, Lynyrd Skynyrd said: “Due to unforeseen circumstances, Lynyrd Skynyrd is unable to perform the next four shows. Longtime band member Rickey Medlocke has tested positive for COVID-19. Rickey is home resting and responding well to treatment.”

Allen has extended his set list to open the show. He also performs a duet with Paisley on current hit song “Freedom Was A Highway.”

___

Former Pittsburgh Steelers star safety Troy Polamalu has recovered from a bout with COVID-19 and will attend the Pro Football Hall of Fame inductions.

Polamalu, a member of the class of 2020, has been at home since late last month and his status for the enshrinement ceremony had been in doubt. But he was cleared medically to travel to Canton and he took part in the Hall of Fame parade in the morning. He missed the Gold Jacket Dinner on Friday night when other members of the classes of 2020 and 2021 received their hall jackets.

A four-time All-Pro who twice won Super Bowls, Polamalu had to wait an extra year to be inducted because of the pandemic.