Part 3. Even as a central lesson of the 60s is the indispensability and obligation of struggle, it is also a central and sustained teaching and lesson of Kawaida that regardless of the other battles we must and might wage, the first and continuing battle is the battle is to win the hearts and minds of our people. And as we said in the 60s and constantly reaffirm, unless we win this battle, we cannot win any other. Thus, we of Us called for a radical revolution in views and values, an overturning of our negro selves and recovering the African within us.

We said that inside every negro, there is a Black person, an African, striving to come into being and we must wage a daily struggle to bring into being and sustain the best of what it means to be African and human in the world. For we are American by habit and African by choice. And we must choose every day to be African and to embody the instruction of our ancestors that African means excellence in how we understand and assert ourselves in the world.

Thus, we maintained, following Min. Malcolm, that we needed a cultural revolution that precedes, makes possible and sustains the political revolution. Clearly, we need to wage the political struggle to free ourselves, but we can’t really free ourselves, if we don’t be ourselves, if we deny, diminish or deform who we are as African persons and an African people. And likewise, we can’t fully be ourselves, if we don’t free ourselves and create space for us to come into the fullness of ourselves as persons and a people. So, we wage a simultaneous double struggle, stressing each aspect in its turn. Again, following Malcolm, we said “We are a nation within a nation”, a cultural nation striving to come into political existence, a people seeking power over the space it occupies, over its destiny and daily lives.

In the call for peace and security, we must not join or mimic the unthoughtful or unjust who talk of peace without justice, a submission to evil and injustice for the sake of calm or the comfort of the ruling race/class. We must refuse and reject calls for a repressive peace imposed by police violence or what Frantz Fanon calls the “peaceful violence” of the system which uses institutional violence without the show of weapons. Indeed, the policies and practices of its structured domination, deprivation and degradation is daily violence against the body, heart, mind and soul.

It is the violence of a degrading and deficient educational system, the denial of access to affordable and adequate housing, healthcare and employment, and the means to make a living and a decent and good life. It is the violence of the media, making us into self-mutilating mascots, “blackish” caricatures of humanity, and turning our social savaging and suffering into entertainment for the ruling race. And it is the violence of displacing our people from historical living spaces, replacing them with Whites, dispersing us to the winds, destroying community and centralized sites of culture, and calling it gentrification to camouflage its race and class character and the human casualties and social chaos and ruin it causes and leaves in its wake.

So, we must continue to rise up and resist in righteous anger these and all the other evils and injustices of oppression and White supremacy. For what do we have to lose except the little space that has been left for us to praise them for their oppression in this citadel of White wealth and power, this self-declared democracy of Whiteness and wealth? And as we continue to rise up in righteous and relentless struggle, let us also remember this lesson also born and reaffirmed in struggle: know that we are our own liberators. Indeed, the oppressor is responsible for our oppression, but we are responsible for our liberation.

Another lesson we bring from the 50 years of righteous and relentless struggle is the important role art (creative production, creativity activity) can play in the struggle. Author and literary critic, Larry Neal, noted that “In Watts after the Rebellion, Maulana Karenga welded the Black Arts Movement into a cohesive ideology which owed much to LeRoi Jones (Amiri Baraka)”. Neal speaks here of the influence Kawaida had on the works of not only Baraka, but also on a wide range of artists, i.e., Haki Madhubuti, Kalamu ya Salaam, Val Gray Ward and the artists of Kuumba Theatre, later Gwen Brooks and August Wilson and others. Kawaida contended that Black art is not simply art for art’s sake, but art for our people’s sake, that it must raise and praise the people, expose and attack the oppressor and open new horizons for our people to be themselves, free themselves and come into the fullness of themselves. In a word, art must be functional, collective and committing.

From our work with Dr. Harry Edwards, chair of the Olympic Project for Human Rights and organizer of the Black Olympic Boycott, we also learned the lesson of the important role Black athletes can play by taking a stand and advancing the interests of the struggle. This is clearly exemplified in the draft resistance by Muhammad Ali, 1966; Tommy Smith’s and John Carlos’ Black Power demonstration at the Olympics in Mexico,1968; Arthur Ashe’s organization of athletes against apartheid, 1973; and more recently the Black football team members at the University of Missouri who supported the students demands and struggles against campus racism, and Colin Kaepernick’s demonstration against the oppression and violence against our people.

Important also was the resistance of Black athletes like Jim Brown, Craig Hodges, and Curt Flood who resisted dehumanizing trading practices and especially Flood’s struggle which opened the way for free agency and bargaining rights in the sports world and against brutal capitalist profit-making practices. They all paid a heavy price for the sacrifice and struggle and offer a model for all others who decide to join them.

It is Min. Malcolm again who taught us that we are not to act responsibly in the eyes and interests of our oppressor, but be responsible to and acting responsibly for our people. Indeed, we are to act outrageously irresponsible in the eyes and evaluation of the oppressor. For as Malcolm taught, to be responsible in their unjust, immoral and undemocratic judgment is to betray the trust of our people. For we do not come to the battleground to concede, but to confront; not to be silenced and sidelined, but seize the center and speak on behalf of our people, especially, Malcolm says, “the downtrodden and dissatisfied”. And we are not to compromise at the expense of our people, but to hold the line, build united fronts, rebuild the overarching Movement, fight the good and victorious fight, and lay the basis for a larger broader radical struggle to seriously transform society in the interest of freedom, justice, human good and the well-being of the world.

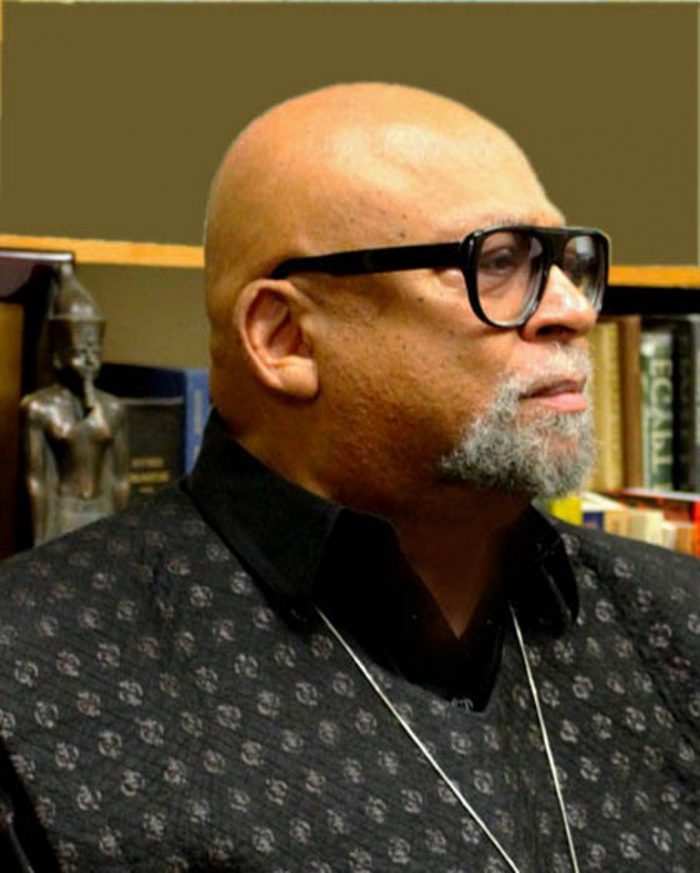

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, The Message and Meaning of Kwanzaa: Bringing Good Into the World and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis,