The appreciation and preservation of the integrity, beauty and expansive meaning of Kwanzaa are rooted in the hearts, minds and practice of African people. It is they who must and do uphold and defend its integrity, recognize and reaffirm its beauty and constantly seek to understand and share its expansive meaning. This calls for and requires a self-conscious commitment to Kwanzaa, celebrating the holiday with the mindfulness, care and joy it deserves, sharing it with others and living its principles, not only in celebration, but also in anchoring, preserving and advancing Black people and Black life in all their dignity, beauty, good, strength and human potential and possibilities. And this also calls for and requires constant vigilance, ongoing struggle and a self-conscious resistance to and rejection of any and all attempts to redefine or render Kwanzaa in ways that violate its integrity and reductively translate its beauty, its core and expansive meaning.

Over the decades of its creation and coming into being, we as a people have waged countless battles to defend Kwanzaa against efforts to make it a facsimile of other holidays, to appropriate and import available imagery and symbols from other cultures and celebrations, and diminish its value and message as a distinct and unique cultural celebration of African peoples, in a word, a celebration of African family, community and culture.

When the U.S. Postal Service released its first stamp in 1997, as a result of Black peoples’ request, the African American Cultural Center (Us), as the international headquarters of Kwanzaa, reached out to ensure representation of Kwanzaa that respected its integrity, appreciated its beauty and reflected its expansive meaning. And the USPS responded positively, allowing for a mutually beneficial exchange and creating a product and process we all could embrace and advance. Indeed, that stamp depicting the central meaning of Kwanzaa as a celebration of family, community and culture was the best stamp and accompanying script produced. Since then, there has been no real communication and exchange and often the stamps became progressively less representative of Kwanzaa and its values.

Moving from the first stamp in 1997 with its black, red and green emblematic colors, a family of a man, woman and male and female children, mazao (crops), zawadi (gifts), the renditions have declined in adequate representation of the symbols and core meaning of Kwanzaa. In 2004, there are only people with beautiful clothes. In 2009, there’s a rather impressionistic rendering in “bright green, red, gold and black” with figures resembling a man, woman and a female child with an interesting hairstyle. In 2011, there is a beautiful family, but it is lighting a menorah instead of a kinara. And in 2013, there is a man and child, and as we learn from the description, a woman, although she in the background and appears as a girl in comparative size and countenance. In terms of the 2011 stamp, the family was depicted with a menorah; it is important to note that substituting a Hanukkah menorah for a Kwanzaa kinara confuses and conflates two distinct candleholders and cultural traditions, and thus, violates the integrity of both Kwanzaa and Hanukkah. Also, it should be noted that the artist is African American and the director is Euro-American.

On this stamp of 2016, there was no outreach at all and it is clearly the least representative of Kwanzaa. It is marred by both what it presents as well as what it leaves out. Its central figure is a large woman who looks like a Native American or Latina with straight, long shoulder length hair. Even the patterns on the collar of her dress can easily be seen as Native American. Thus, although the accompanying script says it features “an African American woman as the embodiment of Africa,” she clearly appears otherwise. In fact, such a “Big Mama alone” image can easily conjure up stereotypical conceptions of the Black woman as looming large and alone, consoling herself with dreams and schemes of having long, straight hair, even if she has to buy it. I’m not sure how or why the African American artist and the Euro-American designer of the stamp came up with this or decided not to consult. Given the results, it could only have helped.

The script speaking of Kwanzaa’s roots in first fruit harvest celebrations states that “Kwanzaa synthesizes and reinvents these tribal traditions as a contemporary celebration of African American culture.” This, of course, is incorrect and misleading. It is true I did synthesize, i.e., research, select and develop varied African cultural practices into a harmonious whole, but I did not “reinvent” or “invent” Kwanzaa. I created Kwanzaa as an intellectual product and cultural practice, a tradition born of study, legacy and struggle. Moreover, to talk of “tribal tradition,” is to use the colonial language of anthropology, even if other Africans use such terms. My engagement was not with so-called “tribal” tradition, but with communal traditions drawn from varied formations—from small ethnic groups to nations, states and federation of states. Colonial language like tribal, chief, hut, pagan, animistic and host of related dignity-denying and status-diminishing terms have no part in Kwanzaa discourse nor in the discourse of a self-defining and self-determining people.

The Postal Service script also takes the liberty of redefining the meaning of the colors in the context of Kwanzaa. It says, “Red indicates the blood shed during struggles endured by those of African descendants, black symbolizes the African people and green signifies growth and renewal.” But actually black is for Black people, red is for struggle and green is for the hope and future forged in struggle. It might seem the changes are minor, but they are not. For not only are alternations made that should not be made for reasons of accuracy and authenticity, but also they shift the emphasis of red and green from their original rootedness in struggle. Red becomes a color of suffering endured rather than active resistance, and green becomes a dictionary definition of growth and renewal, rather than a symbol of struggle to frame and forge a free and flourishing future. All this and more is available in the authoritative book on Kwanzaa, by me, its creator, titled Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture, and www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org, for those who wish to know, honor and accurately depict the holiday, the people and their culture.

As I’ve said, many times, one of the greatest powers of a society is its capacity, or the capacity of its ruling race/class to define reality and make others accept it, even when it’s to their disadvantage. If we accept others’ definition of us, our families, communities and culture or our people as a whole, it is clearly not from our values or vantage point and certainly not to our advantage. We live in a consumerist society which simplifies the complex, devalues the valuable and reduces people and things to market-driven conceptions and practices of seduction and sales. Moreover, such a process privileges traditions of the dominant group and feels no need to accurately understand and depict others or their cultures. Our task is to demonstrate the unacceptability of this, to resist and reject such practices and the inferior and inadequate products from them. After all, Kwanzaa was born in struggle in the midst of the Black Freedom Movement. And it was and remains an act of freedom and a celebration of freedom, the culturally grounded and empowering practice of self-determination in the elevation, advancement and liberation of our people.

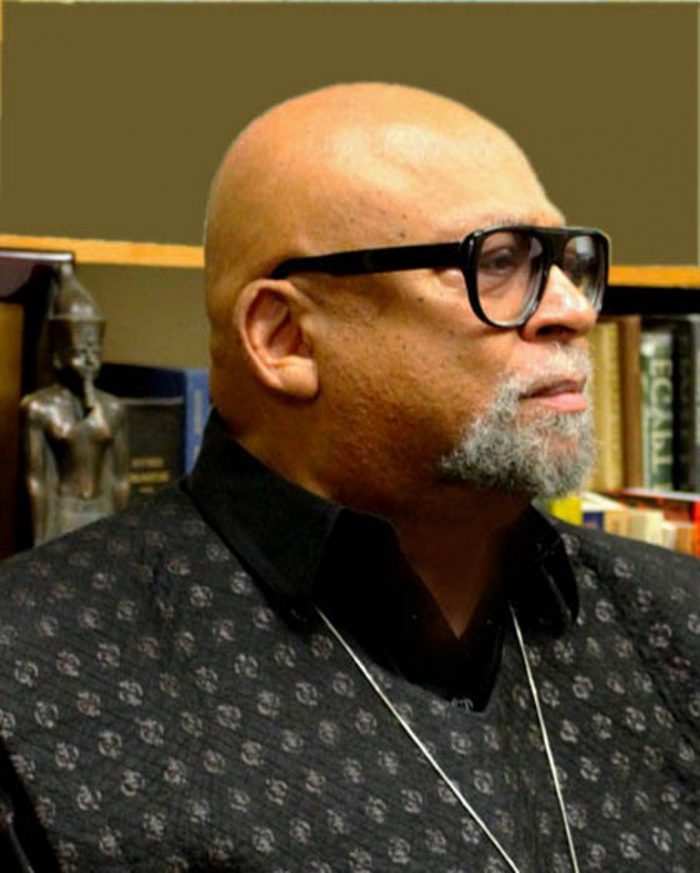

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.