The Watts Revolt of August 11-16, 1965, stands as a major marker and monument in the history of the Black Liberation Struggle. Not an isolated or unexpected event, it came as an act of collective resistance to police violence and brutality, merchant exploitation and humiliation, and sustaining systemic racism. Although these conditions were the immediate and overarching cause, the revolt, as a radical practice of the right to resistance, was clearly rooted in the long history of African revolt and resistance. It is a history of resistance that extends from resistance to capture and conquest in Africa and ship mutinies, to varied forms of day-to-day resistance, cultural, political and economic resistance, as well as armed resistance, alone and in alliance with Native Americans and Mexicans in this country and context of oppression.

The August Revolt called by its epicenter name, Watts, also was a result of the legacy and lessons of Haji Malcolm X, beloved teacher, honored martyr and Fire Prophet who sensed and saw the coming fire storm and forest fire of revolt and resistance destined to engulf America in the 60s. He prophesized liberation and the fire this time. Even before Watts and Los Angeles and other 250 cities were set on fire, he predicted the coming revolt and revolutionary struggles against racism and White supremacy. He stated that “America is the last strong hold of White supremacy. The Black revolution, which is international in nature and scope, is sweeping down on America like a raging forest fire. It is only a matter of time before America itself will be engulfed by Black flames, these Black firebrands.” And so, it was. Watts, like Ferguson, was the spark that ignited a forest fire of similar struggles and revolts across the country afterwards.

Watts assumed a special status and meaning in the Black Liberation Movement because of its early impact on the emerging Black Power phase of the Black Liberation Movement. Coming as the first major revolt with national impact, the Watts Revolt raised consciousness and possibilities of revolt as an important means of struggle. And though it and other rebellions, revolt became a signature mode of resistance and defining feature of the Black Power period of the Black Freedom Movement. And thus, it became a conscious and customary reference for radical and revolutionary struggle, claiming, discourse and daring.

The conditions and consciousness which the Revolt produced, generated new activity of struggle, organization and institution building. And our organization Us was deeply involved in this process and practice. Us came into being in the spirit, tradition and practice of the Revolt. As self-conscious keepers and spreaders of the fire and flame of the Fire Prophet, Haji Malcolm X, we strived to reaffirm his teaching in word and deed. We initiated and engaged in processes and practices of education, mobilization, organization and confrontation as pathways to radical self and social transformation. We stressed cultural revolution that proceeded and made possible political revolution. Or as we said in the Quotable Karenga, “Culture provides the basis for recovery and revolution.” That is to say, recovery of our consciousness of ourselves in deep, expansive, dignity-affirming and life-enhancing and liberating ways. In a word, we taught that in order to free ourselves we must be ourselves. It is in this context that Kawaida philosophy was conceived and from it the Nguzo Saba and Kwanzaa were created and our four-point program of work, service, struggle and institution-building was developed and initiated.

On the local level, we built the African American Cultural Center (Us), co-founded and co-led the Black united front, the Black Congress, the Brotherhood Crusade and the Community Alert Patrol to monitor and resist police violence and brutality. We helped build and sustain the Watts Summer Festival, and one of our founding members, Tommy Jacquette-Halifu, who also led an important Watts-based organization, SLANT, assumed leadership of the Festival and maintained it as a radical reminder of its origins in struggle and rightful remembrance of the martyrs and sacrifices until his transition.

Also, we were involved in the co-planning and advocacy for the Kedren Community Health Center and the Watts Health Foundation. And we co-planned and named Mafundi Institute for creative and performative artists, and the Ujima Housing Project for working class and lower-income families. This became a model for the Kawaida Towers in Newark, first proposed in the 60s and now realized recently. Indeed, the name was given in honor of our philosophy of life, work and struggle, Kawaida. Finally, we taught Black and Brown organizers at the Social Action Training Center and worked with its leaders to develop initiatives of social action and advocacy.

Here we are now at the point of commemoration again this year. And we are, as always, at this critical juncture of remembrance, reflection and recommitment and we ask ourselves what are the lessons to be learned here? And what are we to do to continue, intensify and expand the struggle, keep the faith and hold the line in our liberation struggle? Indeed, the problems and challenges of the past persist and have increased in this time of pandemic and the continuing pathology of oppression. And if there is one continuing lesson to be learned from the Watts Revolt and all others, it is that it is the right to rebel against oppression, evil and injustice. And we must reclaim Watts and all our other revolts and the right to rebel which they represent.

It is in appreciation for the right to rebel that we do not define the Watts uprising as a riot, an unrestrained outbreak without political aims or motivations. Rather, we define it as a revolt, a collective act of resistance to the established order, motivated by political aims and ideas. As noted above, the concept and practice of revolt was linked to Black Power in an inseparable way. And that we, I, define both our revolts and Black Power as a collective act and struggle of people to achieve and sustain the goals and goods of: self-determination, control of our space, destiny and daily lives; self-respect, grounding in our own culture which affirms our identity and dignity as persons and a people; and self-defense, the right and responsibility to defend ourselves against systemic oppression, violence and injustice by any means required and appropriate to the task. Also, Watts and our other revolts demonstrate that we must demand in word and fierce, committed and uncompromising struggle our right to live lives of dignity and decency. After the revolt, our people demanded and intensified the fight for decent jobs and adequate income; accessible and adequate housing and healthcare; quality education; teen programs; increased and effective political representation; an equitable share of community development resources; equitable support for cultural institutions; prisoners’ rights; freeing of political prisoners and serious programs of reentry and support; and as always, the end of police violence, unjust incarceration and the systemic racism in which all these evils are rooted.

This too is a lesson from Watts by way of Frantz Fanon and Amilcar Cabral. And it is that we can start a revolt spontaneously, but we can’t sustain it, Fanon tells us, without “clear objectives, a definite methodology and above all,” organization of the masses. And thus, as Cabral reminds us, we must “mask no difficulties, tell no lies and claim no easy victories.” For as we say, “There is no substitute for an aware, organized and engaged people constantly involved in a multiplicity of activities to define, defend and advance their interests.” Also, always for us, as Nana Mary McLeod Bethune assures us, our struggle must be world-encompassing in conception and practice. For “our task is to remake the world. It is nothing less than this.” And rightly understood in the context of revolt and revolution, we are ultimately, the Hon. Marcus Garvey’s liberating whirlwind and Watts’ and Ferguson’s transformative fire, the ongoing source and instructive symbol of radical life changing and life-enhancing struggle in this country and the world.

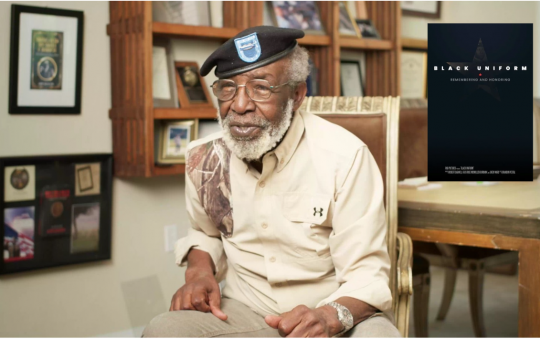

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org.