Part II. It was Min. Malcolm X who taught us to cultivate a world-encompassing consciousness, not only as pan-Africanists committed to the liberation of Africans everywhere, but also as part of the worldwide revolution and liberation struggle going on and redrawing the map of history. He taught that we, as African people, were part of that global struggle of the oppressed against oppressors. And he assured us these struggles represented the rising tide of human history.

Studying Third World Liberation Movements, we learned from Mao Ze Dong and the Chinese people ideas and practices rooted in Mao’s teachings reflected in concepts he put forth such as “power to the people,” “pick up the gun” and “a people united cannot be defeated.” And from the Cuban people and its leader, Fidel Castro, we learned that it does not matter if our oppressor condemns us, for our struggle and history will absolve and define us, and that with faith in and love of the people and a clear and correct plan of action, we can achieve the impossible. And we learn from the Vietnamese people and its leader, Ho Chi Minh, that a small nation can defeat a large nation, that the preparation and will of the people are decisive and if an arrogant person or nation mounts a tiger, they must remember, the problem is how to get off. But above all, we absorbed the spirit of possibility and promise of the era if we engaged in righteous and relentless liberation struggle to be ourselves and free ourselves.

None of this is to say there were no problems with all revolutions from which we learned; consider the American Revolution. But it is important not to deny beneficial lessons well-taught and well-learned. Moreover, we ourselves had and have lessons to teach the world, even as we learn from it as we continuously strive for excellence in all we think, feel, say and do.

It is this context of righteousness and relentless struggle against racism and White supremacy and its national and international forms that the Black Freedom Movement emerges and develops. It has two phases: the Civil Rights Phase (1955-1965) and the Black Power phase (1965-1975). Although it is common practice to call both phases the Civil Rights Movement, that is not only wrong, but an act of historical erasure and part of the established order’s efforts to deny our people the right to define and claim their own history, struggle and victories.

Civil rights was clearly an emphasis in the Black Freedom Movement, but, as Min. Malcolm taught, our struggle has a larger arc of moral meaning as a human rights struggle. For it speaks to rights no government can give us, rights we were born with, including the first and fundamental rights – the right to life, liberty and security of person. Indeed, the three most often demanded, chanted and aspired to and fought for human rights were freedom, justice and equality embraced by all leaders of the Movement, both the Christians and the Muslims, SCLC and NOI. Thus, our oppressor cannot be our teacher and must not be allowed to redefine our freedom struggle in the reductive terms of a civil rights movement.

Our shared goals were freedom, justice, equality and power, the latter goal added during the Black Power period of the Black Freedom Movement. Here it is important to note that the goal of equality was not to be equal to Whites in any sense that suggested we were not already equal in dignity and human rights. Rather, the demand of equality was a demand for equal treatment and equal recognition of our rights. Indeed, the oppressor exhibited no moral qualities, social psychology or humane behaviors we wanted to adopt or emulate. In fact, we defined ourselves and our liberation struggle for a new society and world in contrast to the unfreedom, domination, deprivation and degradation that characterized his system of reasoning and rule.

The Civil Rights Period of the Black Freedom Movement brought us the important transformative victories: Brown vs. Board of Education and all the initiatives launched to make it a living reality. It won the 1964 Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 and Affirmative Action. And it made gains in ending legal segregation, although the struggle against de facto segregation remains. And this period of the Black Freedom Struggle also produced rich and varied forms of education, organization and actions, i.e., demonstrations, marches, sit-ins, civil disobedience, party building, voter education and registration, and self-defense initiatives.

The Black Power Period of the Black Freedom Movement emerged as the Civil Rights Period became historically exhausted, having achieved many of its legislative and judicial gains and having begun to dismantle the people-focused structures, issues and processes of struggle that yielded their gains. It was a premature move that led to brain drain and institutional weakening and a shift from community focus to integration in U.S. society. Thus, emerged the call for Black Power, power to define ourselves, defend ourselves, develop ourselves, and enjoy lives of dignity and decency, i.e., being duly respected and having the necessities of life and the social capacity for human flourishing.

We opened up critical space in the Black Power Movement by providing intellectual and practical initiatives. We defined Black Power as the collective struggle for and practice of self-determination, self-respect and self-defense. By self-determination, we meant and mean controlling the space we occupy, the politics, economics and culture of our community, and effectively participating in decisions that affect our destiny and daily lives. By self-respect is meant rightfully reaffirming our identity and dignity rooted in our culture and struggle and being the center and subject of our own lives, history and culture. By self-defense, we meant the right and responsibility and capacity to defend ourselves and achieve our freedom, as Malcolm said, by any means necessary. And by any means necessary, I read Min. Malcolm as meaning, by any means the oppressor compels us to engage and by any means required by us in service and sacrifice for our freedom.

During the Black Power Movement, we continued to expand the realm of human freedom and to compel the country to face its racist self and come to terms with our righteous demands. Our organization Us and other Black Power organizations, organized against and resisted systemic racist violence, struggled against police violence, organized units of self-defense, built youth movements, and resisted the draft into what we defined and denounced as a racist and imperialist army. We engaged in massive political and cultural education, mobilization, organization and confrontation. We built independent schools, cultural centers and other institutions, and Black United Fronts to achieve community control and development and advance our liberation struggle. In addition, we advanced pan-African and international initiatives, built Third world alliances with Native Americans, Latina/os and Asians, participated in union and party building, and supported community-oriented politicians.

Moreover, we built Black student unions and established Black Studies in the academy, laying the basis for other Ethnic Studies and the creation of a multicultural quality education and inclusive university. And we raised the moral imperative of reparations as both what society owed us, but also as a means of healing, repairing, renewing and remaking ourselves in the process and practice of repairing, renewing and remaking society and the world. In the midst of savage oppression, we determined the remedy to be revolutionary resistance, the strategy to be righteous and relentless struggle everywhere, and the ultimate goal to be a radical and liberating transformation of self, society and the world in the interests of African and human good and well-being of the world.

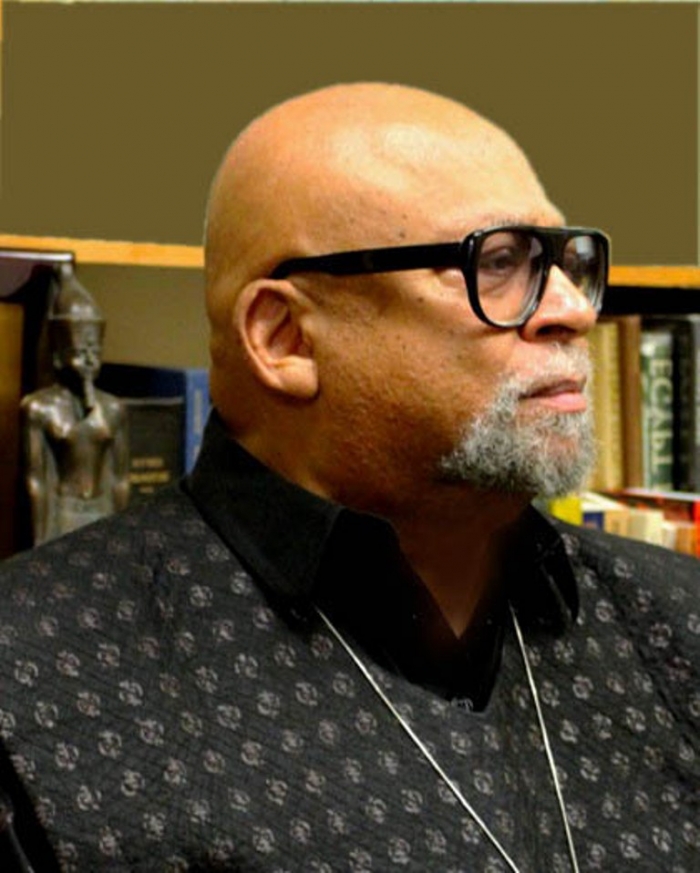

Dr. Maulana Karenga, Professor and Chair of Africana Studies, California State University-Long Beach; Executive Director, African American Cultural Center (Us); Creator of Kwanzaa; and author of Kwanzaa: A Celebration of Family, Community and Culture and Essays on Struggle: Position and Analysis, www.AfricanAmericanCulturalCenter-LA.org; www.OfficialKwanzaaWebsite.org; www.MaulanaKarenga.org