Biddy Mason

Maggie L. Walker

A.G. (Arthur George) Gaston

THE HUDSONS BROADWAY FEDERAL BANK

Prominent Businessmen & Women

“They have led the way and set the standards for some of the best in the business”

Despite tremendous odds, Black men and women entrepreneurs have pioneered the way, inspired Black People and helped the nation maintain its status as the richest country in the world. Their work has produced business giants including Madame C. J. Walker, John H. Johnson, Percy Sutton, Berry Gordy, Comer Cottrell, Eula McClaney, Robert Johnson, Don Barden, Sheila Johnson Newman, Oprah Winfrey and many others.

IN HONOR OF BLACK BUSINESS MONTH, THE SENTINEL PRESENTS:

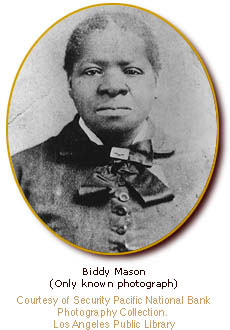

BIDDY MASON

Bridget “Biddy” Mason was born as a slave in Hancock County Georgia in 1818 and she rose to become a nurse, a real estate entrepreneur and a philanthropist defying insurmountable odds at a time when women could not vote and Black people were treated as “no-class” citizens in America. She was brought to California as a slave in 1851, crossing the plains on foot–from Georgia–while driving a herd of sheep behind her owner’s wagon, first to the Utah Territory and then to San Bernardino, California. During that time, free(d) Blacks had an extremely efficient communications network and closely monitored the status of every Black person that came or was brought to California, then a free state. After four years in California, Mason’s master decided to move to Texas with his slaves. Members of the Black community summoned the sheriff thereby interrupting his plans to take his slaves with him. They hired legal counsel for the slaves and had the master served with a writ of Habeas Corpus resulting in Mason’s petitioning a Los Angeles court for her freedom. Since California was a free state, the Los Angeles court granted Mason’s petition along with her three daughters: Ellen, Ann and Harriet, and ten other slaves who were owned by the same master. Mason’s daughters were reportedly the children of her slave-master. Mason and her daughters settled in Los Angeles and she began working as a nurse and a mid-wife; she worked hard, lived frugally and had a burning desire to be economically independent. She then began to invest in real estate, becoming one of the first Black women to purchase land in the city–two parcels (about 10 acres) between Broadway and Spring Street for $250 in 1866. The single acquisition occurred a mere ten years after gaining her freedom; in 1884, she sold a portion of that property–now the heart of downtown Los Angeles–for $1500. Mason did not immediately live on the property, but she did rent another house nearby in which she and other members of the Black community established the First African Methodist Episcopal (FAME) church in 1872. She developed the remaining parcel of the Broadway/Spring property into a two-story brick building and moved into the top floor. By then, she was one of the wealthiest Blacks in Los Angeles County. As the city grew, most of Mason’s investments became prime urban real estate in what would become downtown L. A. Much of Mason’s good works were demonstrated beyond her life through her legacy which included an accumulated fortune of $300,000. She died on January 15, 1891 at the age of seventy-three and was laid to rest in Boyle Heights at Evergreen Cemetery. Her obituary noted: “she was a pioneer humanitarian who dedicated herself to forty years of good works.” Her massive real estate holdings passed on to her children. During the 1920s, the Spring Street area became “Wall Street” West and the office building housed banks, accounting firms and high-profiled law offices. Mason’s properties eventually became casualties of the Great Depression and her children were unable to hold on to them. Finally, the properties became part of a parking lot and as the financial center shifted to the west of downtown, all references to Mason were obliterated. However, her grandson, Robert C. Owens, inherited much of her business acumen and followed in her footsteps becoming a wealthy, real estate developer during the mid-nineteenth c entury.

In 1988, nearly a century after Mason passed, Mayor Tom Bradley, along with members of FAME attended a ceremony where a tombstone was unveiled marking her grave for the first time. A year later, a series of plaques commemorating her life were placed in a park in an area she once owned.

MAGGIE L. WALKER

Maggie Lena Mitchell (Walker) was born to Elizabeth Draper Mitchell, a former slave and a White man, Eccles Cuthbert. Early in her life, her mother married William Mitchell who was also a former slave. Her parents worked in the home of an abolitionist and after a few years of exemplary service, they were freed. Maggie’s stepfather (Mitchell) got a job as a “maitre d” at a prominent hotel and the family moved into a small house nearby. At an early age, Maggie’s stepfather was killed and she had to help her mother do the laundry business in order to take care of her and her brother. Maggie Mitchell attended Lancaster School and then the Armstrong Normal School where she graduated in 1883. At age fourteen, she became a member of the Grand United Order of St. Luke, an African-American fraternal and cooperative insurance society that had been founded in 1867 by a former slave, Mary Prout, in Baltimore. Maggie taught at her alma mater, the Lancaster School, until her marriage in 1886 to Armstead Walker, Jr., a building contractor. After having three sons, she went to work part time as an agent for an insurance company, the Women’s Union, while attending night school for bookkeeping. She also volunteered at St. Luke and eventually worked her way up in 1889, to become the executive secretary-treasurer of the renamed organization, the Independent Order of St. Luke. Walker started publishing the St. Luke Herald in 1902 to publicize and promote the order. In 1903, she opened the St. Luke Penny Savings Bank and became its first president. She had often dreamed of turning “nickels into dollars” by pooling money and then lending it out at reasonable rates. Hers was a dream fulfilled for she reasoned if Black people put their money together and “loan it out among ourselves then the interest will be ours.” And it worked. She earned the recognition of being the first women to charter a bank in the United States. The bank severed relations with St. Luke fraternal order and then merged with two other Black banks to form the Consolidated Bank and Trust Company. She became the chairwoman of the board. Walker supported many charities and organizations that worked to better the quality of life of Black people such as the Urban League, the Virginia Interracial Committee and the NAACP. In 1904, she bought a house consisting of nine rooms and eventually expanded it to 22 rooms, installing central heating and electricity. Her son, Russell, accidentally shot and killed her husband, his father in 1915, and thereafter, he suffered long bouts of depression; he died in 1923. Her mother and her (Walker’s) son both lived with her. There were other tragedies in her life from which she never fully recovered. Walker fell and injured her kneecap in 1907 causing her to use a wheelchair, and in addition she also suffered from diabetes. She had to install an elevator in her house for her convenience and had her car adjusted to accommodate her wheelchair. She died in her Richmond, Virginia home on East Leigh Street that has since become the Maggie L. Walker National Historic Site. It still contains the original furnishings. The Consolidated Bank and Trust Company is still in existence today; it is the oldest continuously operating Black bank in the U. S.

A.G. (Arthur George) GASTON

Arthur George Gaston affectionately known as A.G. Gaston was born of very humble beginnings and into harsh poverty in Demopolis, Alabama–the Deep South. He was the grandson of slaves. Although he was unable to gain a basic education, he became one of the most influential and richest men in Birmingham, the largest city in the state. After serving in an all-Black military unit in World War I, he worked in a coal mine. His keen insight for business was always ever present as he sold lunches to his fellow coal miners. He had the ability to take the proverbial lemon and make lemonade. He never finished high school but with sheer will and determination, he launched a series of small, “mom-and-pop” businesses that mushroomed into a phenomenal business empire consisting of communications, real estate and insurance in part. He founded the Booker T. Washington Insurance Company and created the Booker T. Washington Business College primarily to afford young Black people the opportunities that he had been denied. He was determined to make a difference for himself and for Black people. In doing so, he became one of–if not the wealthiest Black man in America at that time. His business empire also included a bank, a motel, radio stations, senior citizen’s home and a construction firm. Gaston overcame staggering odds, and though his wealth and influence bore comparison with some of the great captains of industry–Carnegie, Mellon, Rockefeller and Ford–he traveled a much greater distance to arrive at the same destination as the aforementioned. The keys to his success were hard work, honesty, dependability and thrift. He was a strict adherent to the philosophy of Booker T. Washington, for whom he named some of his early businesses. He had an undying need and a great attraction to helping young people and to that end, he founded the A.G. Gaston Boys and Girls Club. In his later years, he arranged for his employees to acquire his nine corporations, worth a combined total of 34 million dollars for only 3.4 million dollars, one tenth of their appraised value. Gaston was very close to the civil rights issues facing the South. He considered it his civic duty to help mediate and to offer financial advice to those who were demonstrating in the streets for a better quality of life for all. He provided his negotiation skills and his leverage as a businessman to gain cooperation and win concessions for the civil rights workers and the Black community. A devoted husband, he and his wife, Minnie Gardener Gaston had one son, Arthur, Jr. He was a lifelong member and national officer of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Though he was largely an unlettered man, he received several honorary degrees and became Dr. A.G. Gaston. He was inducted into the Alabama Men’s Hall of Fame in 1999.

THE HUDSONS

Broadway Federal Bank

As the nation’s economic condition worsens, it is fitting to note that a local bank, dedicated to serving the community, has been the forefront working with the community, for the community and in the community for over sixty years. Broadway Federal Bank is synonymous with the name, Hudson: H. Claude Hudson, the patriarch; Elbert, his accomplished son and Paul, his grandson. Since its inception, a Hudson has always been at the helm of the bank, which is now a landmark institution in the Los Angeles community. The mission of the bank is to serve the real estate, business and financial needs of customers in underserved urban communities with a commitment to excellent service, profitability and sustained growth. It also has a broader commitment to employ, train and mentor community residents, to contract for services with community businesses and to encourage its management and staff to serve as volunteers in civic, community and religious organizations. In addition, “Broadway” has enunciated a system of values that complements its mission and correspond with its Community Reinvestment Act (CRA) rating. Beginning with Dr. H. Claude Hudson, a dentist who had graduated from at Howard University in 1913, he settled in Los Angeles in 1923 and continued his active involvement in the civil rights movement with the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP); he had been previously involved with the organization, as president, in Shreveport, Louisiana. (His strong commitment to the civil rights struggle, according to reports, was borne out of an experience that he had witnessing the lynching of a Black man). He continued his dental practice and eventually became the president of the Los Angeles NAACP. In 1929, along with renowned architect, Paul R. Williams (both their families became related), H. Claude built the Hudson-Liddell Building at 4166 South Central Avenue. He then enrolled in Loyola Law School and earned a law degree in 1931. Although he never practiced law in the traditional sense, H. Claude used his legal skills to advance his activities and agenda in civil rights and business. In furtherance of his quest to level the playing field for Blacks economically, he joined together with a group of Black businessmen and founded Broadway Savings and Loan in 1946. After receiving its federal charter and with an initial investment of $150,000, the bank welcomed its first customers in January 1947. It was housed in a three-room office on South Broadway, Los Angeles. Shortly afterwards, the leadership of the bank was taken over by H. Claude, one of the original investors. The focus of the bank was to satisfy the demand for homeownership in the Black community by the post World-War II veterans who were routinely denied mortgage loans by mainstream lending institutions. Having a “captive” market caused the bank to grow quickly and in 1954, it acquired the facilities of a closed department store and renovated it into the bank’s headquarters. (Plans for the renovation were done by architect Williams, who was also one of its founding directors). H. Claude supervised the management as chairman of its board of directors for 23 years while maintaining his dental practice. In 1966, “Broadway” opened another branch in the Midtown Shopping Center. Again, Williams designed the new facility. He remained chairman emeritus until his death in 1989 at the age of 102. Enter Elbert T. Hudson, the son of H. Claude who, like his father, was an attorney who had also acquired a banking credential in 1964. When called upon in 1972, he was ready to take over the family business. He automatically moved into the position of president and chief executive officer (CEO) of the bank. In addition to banking, Elbert T. was also actively involved in the community. He was a member of the board of directors of the Brotherhood Crusade, and was instrumental in making it the premier charitable organization in the Black community during that period. And like his father, he was active in the NAACP. Then came Paul C. Hudson, Elbert T.’s son and H. Claude’s grandson. Also, an attorney, he followed the footsteps of both the elder Hudsons. Upon the retirement, his father as CEO, Paul C. took the reins and moved the institution to a higher level. Elbert T. retired as chairman in 2006 and the board elected Paul C. as chairman; his father remains as chairman emeritus.