Imagine, you’re not feeling well, you go to the hospital. They draw some blood to check for an infection. They send you home with some antibiotics, which you take as instructed. You get better and go on with your life—and doctors discover your cells are unique and begin using them to make vaccines, cure diseases and advanced scientific studies without ever telling you.

Welcome to the life of one Henrietta Lacks.

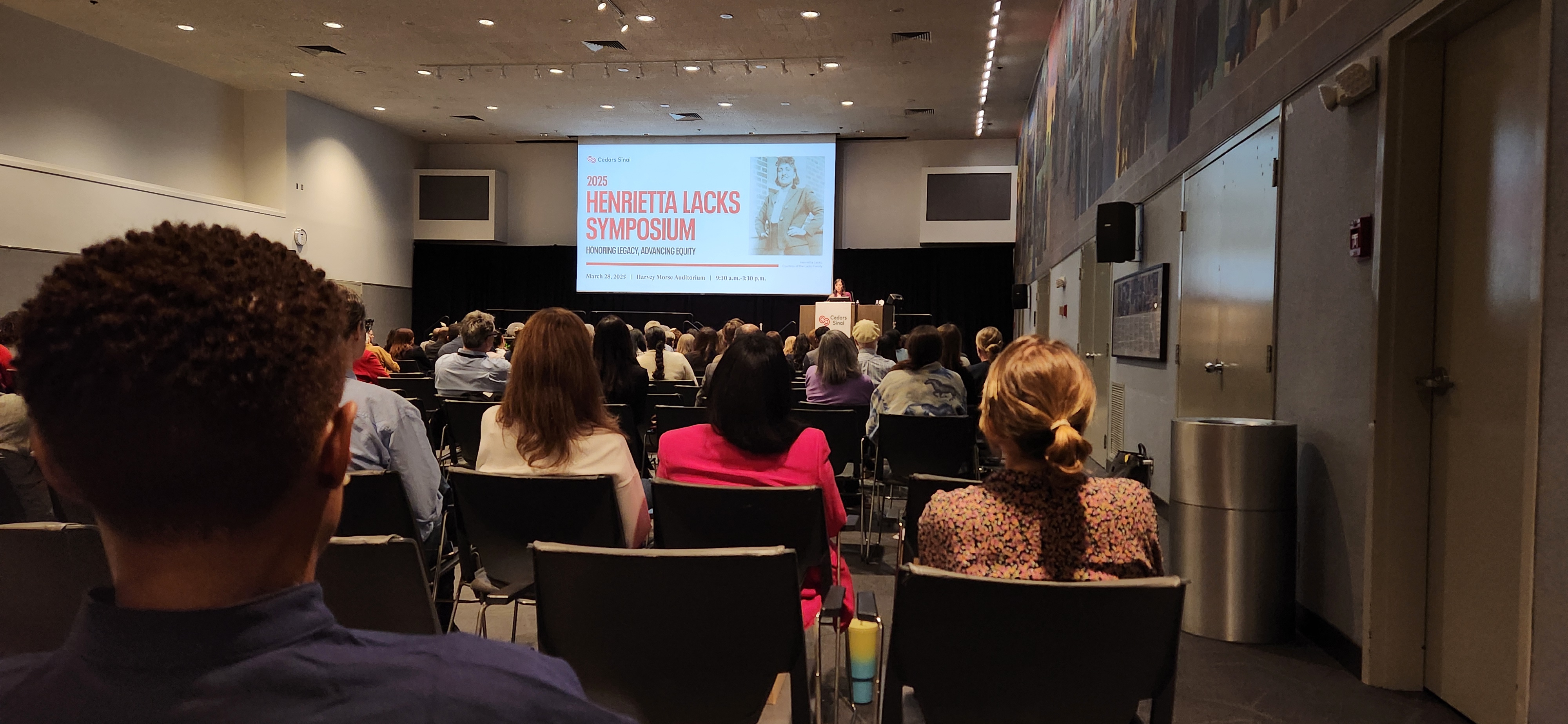

Closing out Women’s History Month, Cedars-Sinai Medical Center held the Henrietta Lacks Symposium on Friday, March 28 with panels, a Q&A session with author Rebecca Skloot (“The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks”) and members of the Lacks family including grandchildren, David Lacks, Jr., Jeri Lacks Whye and great granddaughter, JaBrea Rodgers.

Henrietta Lacks was a Black tobacco farmer whose cells were taken without her knowledge or consent in 1951. Her cells become the first immortal human cells ever grown in the laboratory. Dubbed HeLa cells, they became one of the most important tools in modern medicine, vital for developing the polio vaccine, cloning, gene mapping, in vitro fertilization, and more.

Related Stories

Hidden Empire Teaches NFL Players About the Film Industry

CurlyCon LA 2025: Celebrating the Beauty and Diversity of Natural Hair & Culture

“There isn’t a single person out there who hasn’t benefited personally from HeLa cells, like in many ways and there is a point in this book where everyone turns a page and finds themselves and they see like, oh, I took that drug and that’s why I am in remission from cancer or that’s why I have a child and they’re moved by the story, as a human story,” said Skloot.

“The story is just amazing on its own—it’s astonishing.”

Though Henrietta died in 1951, her cells are still the most widely used in the world. Henrietta’s family remained in the dark until the 1970s, when scientists wanted to do research on her children: Lawrence, David “Sonny” Jr., Deborah, and Zakariyya, to learn more about Henrietta’s cell line. Her children were used in research without their consent, and without having their most basic questions answered, such as, “What is a cell?” and “What does it mean that Henrietta’s cells are alive?”

The international success of Skloot’s New York Times bestseller brought interests in the Lacks family and Henrietta’s legacy. In August 2013, 62 years after Henrietta’s death, the Lacks family reached an historic and unprecedented agreement with the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

After a German lab posted the full HeLa genome online for anyone to see, Henrietta’s descendants came together with the NIH. The end result was the groundbreaking HeLa Genome Data Use Agreement, which sees two members of the family join representatives from the medical, scientific, and bioethics communities on a new panel that reviews research proposals for use of the full HeLa genome sequence data and grants permission on a case-by-case basis.

Henrietta’s cells have helped biotech companies make millions of dollars, yet her family has never benefited from their commercialization. It was only in 2020, the centennial celebration of Henrietta’s birth and the tenth anniversary of the book, when that changed. It was at that time that organizations that utilize the HeLa cells made the first historic gifts to the Henrietta Lacks Foundation.

Skloot spoke to the Sentinel about where her fascination with Henrietta began.

“I learned about it in a basic biology class when I was 16-years-old,” said Skloot. “I learned about HeLa cells, which is like when a lot of people learn about the cells, but I just had a teacher, who knew her name, wrote it on the board and it was like, she was a Black woman and that was it and then, erased the board and I just became obsessed, but nobody knew anything else about her.”

Skloot continued, “I’m 52 now, I’ve spent my entire young adult and adult life either researching it, writing it or talking about it.”

Published in 2010, Skloot worked on the book for 11 years. During that time, she was working with the Lacks family to put Henrietta’s story together.

“The book touches on so many aspects, if you read it,” said Lacks, Jr. “I had a supervisor say, you know we had to read Henrietta Lacks in my business class, I’m like, business class?

“I met somebody that said they were reading it in their ethic class, somebody is reading it in their biology class. People was talking about they love the family part of it, some people was talking about they love the science part it, somewhere in that book, you’ll find something that you like and then it takes you on an emotional rollercoaster, up and down.”

“Honestly, I just think her story needs to be heard—that’s the reason that I’m here,” said Rodgers. “I talk to my friends in school and I tell them because some of my friends, they haven’t read the book, and I tell them that’s my [great] grandmother and she saved millions of lives.

“I think just keeping her legacy alive is something that’s extremely important to me like when I go to happy hour, that’s my little party chat.”

During a panel, Skloot and the Lacks family discussed the importance of talking about family history, withholding information and owning your family narrative.

“It’s interesting, so much of the book is actually about the consequences of not talking,” said Skloot. “It’s generations of scientists, who did not say things to patients and it’s about withholding information, sometimes intentionally, most times, not intentionally, they were just sort of not thinking about it and going along with their science and that’s kind of the story of science.”

“I would say in this age, it’s more important that you live your truth and tell your truth,” said Lacks, Jr. “We know a certain administration wants to rewrite a narrative that fits his perspective, but his perspective is not my perspective.

“It’s up to me to tell my story, my family’s story the way I would like to tell it and how I want my kids to know it.”

“Our dad and our aunt, they really didn’t know who Henrietta was, they never spoke of her,” said Whye. “We didn’t know who our grandmother was and how important she was, so I guess for me to know more about my grandmother, so I can teach my children and my children can teach their children for them to speak up, to know your history, to gain knowledge of, who you are and where you came from, who you came from, is important.”

Nicole Anderson is the executive vice dean of academic administration and vice president of academic affairs at Cedar-Sinai Medical Center. She shared how the symposium came to be and the importance of having it now.

“The idea was from one of our graduate students, Rebecca, she wanted to really honor Henrietta Lacks and all of the amazing medical discoveries and so forth that have resulted from the use of her cells,” said Anderson.

“It’s something that we know may be taught now, but many people still don’t know about the HeLa cells and how outstanding they were. Adding to that, part of the goals where to make sure that we addressed a lot of the health and equity issues as well as the fact that many unethical practices occurred during that time and continue to occur as we’ve learned from Rebecca today.”

“It taught me everything about race in America, privilege—shaped so much about who I am,” said Skloot when asked how writing this book has changed her life.

“I couldn’t even begin to separate it out.”